By Lucy Komisar

Inter Press Service (IPS), Nov 14, 2009

To end poverty, you have to know how it began – with globalisation. No, not the 20th century variety engendered by multinationals and their friends at the IMF, World Bank and WTO. They just codified practices that kept developing countries poor.

French filmmaker Philippe Diaz, in an illuminating documentary opening in New York Friday, traces globalisation back 500 years to the Spanish and Portuguese conquests of the Americas. Diaz shows how the colonial North used the South’s resources to build its industrial base and how its continued control over resources, global trade and debt rules prevents developing countries from ending poverty.

Diaz had produced French feature films such as Bad Blood and The Man Inside before turning to documentaries. He made The Empire in Africa about Sierra Leone. The drama of the new film, The End of Poverty?, is as startling as anything he could invent.

The title is a play on a book by economist Jeffrey Sachs – without the question mark – who, Diaz told IPS, runs all around the world with Bono and these guys claiming that if we bring mosquito nets and fertilisers, it will end poverty.

For example, Diaz is incredulous that Sachs’s book ascribes Bolivia’s economic failure to high altitude. He points out that 30 years ago, Sachs advised the Bolivian government to privatise everything, and today the country is essentially owned by foreign corporations.

Abel Mamani, Bolivia’s water minister, says in the film, In the case of railroads, they have practically disappeared since they were privatised. In the east we don’t have trains anymore. They have been entirely dismantled.

The filmmaker says that the year 1500 is when everything started, the time where Europe expands outside its borders and takes everything it can from Latin America, Africa, Asia – the land and all the other resources.

The moment you take the land away, the only way people can survive is to sell their work for food. You take resources away, you create slavery, poverty.

The film shows how European industrial development was not, as widely asserted, based on the Protestant ethic but on riches accumulated via colonialism.

How do you think countries [like] Belgium, small countries with no resources, built empires? Existing industries were destroyed, even those of better quality, and colonies were forced to buy manufactured goods and equipment from colonial masters, Diaz told IPS.

Eric Toussaint, head of the Committee for the Abolition of Third World Debt in Belgium, describes in the film how The Dutch destroyed the Indonesian textile industry and built a textile industry in Holland. Same for ceramics. The textiles and ceramics that we are told are Dutch are in fact made with techniques they took from Indonesia and specifically from Java, brought them back to Holland and built a wealthy industry.

He adds, In the 18th century the Indian textiles were of a much better quality than those of the British. The British destroyed the Indian textile industry and prevented merchants within the British Empire from importing fabrics and other manufactured products from the colonies.

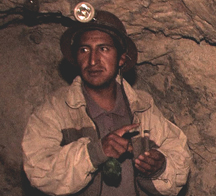

Diaz takes us inside Bolivian mines. He says, In the early days, miners had to work inside mines for six months without ever going out; many died.

Sixty to 80 million still live in slave-like conditions all over the world on plantations and in mines, he explains. It was the same system, we just changed the tools. We don’t have the guns to keep slavery; we have the programmes of the IMF and World Bank, the unfair trade system.

He says ex-colonial powers assured the new countries would be weak and forced to heed the North’s demands by saddling them with debt. When countries won independence, debts of colonial powers used to exploit stolen resources were transferred to new governments – though they had never incurred or benefitted from them. This was enforced by the North via the IMF and World Bank.

Toussaint says that the World Bank, in the guise of helping, increased the debt: Take more loans to build big infrastructure to export your riches. Weakened, countries couldn’t escape the colonial trading system.

Take Kenyan coffee. Diaz points out, The minister of agriculture, Kipruto Arap Kirwa, says in the film that Kenya doesn’t have the right to roast its coffee. They are forced to sell their coffee to the North which refines and packages it. It’s in the trade agreement with the former colonial power. Today, Germany is the biggest coffee exporter, and it doesn’t have a single bush of coffee.

Diaz says, People never got their land and resources back. We interviewed a general of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya that threw the British out. He said, ‘We were

na¯ve.We thought we would get our land back. The British were better organised, they transferred the land from a white minority to a black minority.’ Liberation leader Jomo Kenyatta became the biggest landowner in Kenya.

Kenyan villagers tell how the Dominion Group of Companies in the U.S., which exports vegetables to the United States, destroyed their livelihoods and health. The company built a dam that overflowed and flooded homes and farms.

A woman reports an increase of mosquitoes, malaria, and typhoid. The company does aerial spraying over people working, and a man says that, when you go to nearby public health centres, quite a number of children has been reported dead. He adds, We are now subjected to a life of servitude in our own ancestral land.

The film shows the popular uprising in Cochabamba, Bolivia, after the multinational Bechtel privatised water and doubled prices. A farmer protester says, It didn’t affect only the water cooperatives and water-wells… but rainwater was included in that as well.

Countries that could ignore neo-liberalism did better. Clifford Cobb, an author and historian and executive producer of the film, points out that East Asian economies developed largely behind tariffs. Now, the North prevents the South from imposing such levies while setting tariffs themselves to prevent the import of the finished goods from Third World countries.

This economic model, the film says, has created a global situation in which today, less than 25 percent of the world’s population uses more than 80 percent of the planet’s resources.

Diaz told IPS that for us in the North to maintain this lifestyle, we have to plunge more people below the poverty line in the South. But if the South had cartels to raise the prices of their minerals and agricultural products, the economy of the North would collapse.

Aside from seeing solutions in agrarian reform, tax system changes, and an end to natural resources monopolies, Diaz calls for de-growth. That’s not just eating or driving less, but creating another way of living to avoid what he predicts as the coming resource war when the poor rise up against their repression.

Economists interviewed in the film agreed that the North’s policies are aimed at enriching developed countries, with no concern for resulting poverty.

David Ellerman, a former economic advisor to the World Bank, says that we want to integrate them into an international economic order and to some extent political order, and so even the very definitions of development, the very definitions of, you know, local industry and so forth is all geared in a very natural way to the needs of the North and extracting resources, extracting cheap labour, not creating genuine foreign competition.

Edgardo Lander, a Venezuelan historian, says neo-liberalism in Latin America meant a profound process of deindustrialisation. He explains, It reintegrates Latin American economies and returns Latin America to basic production.

Factories would be based on cheap labour. Michael Watts, a U.S. author and professor, explains capitalism’s need to dispossess people: You can only get someone to work in a factory if they don’t have access to land.

Susan George, Transnational Institute chair, says: Sub-Saharan Africa, which is the poorest part of the world, is paying 25,000 dollars every minute to Northern creditors. Well, you could build a lot of schools, a lot of hospitals, a lot of jobs – you could make a lot of job creation, if you were using 25,000 dollars a minute differently from debt repayment.

So there is this drain, and I think people don’t understand that it is actually the South that is financing the North. If you look at the flows of money from North to South, and then from South to North, what you find is that the South is financing the North to the tune of about 200 billion dollars every year.

Story on IPS site

Pingback: Das Thema in Stichpunkten «