By Lucy Komisar

Zero Mostel — consummate actor, painter and personality — was a presence in American films and stage for decades, except for a brief hiatus called McCarthyism. Zero was iconoclastic, cynical and flip. He scowled and shouted in a voice that was stentorian.

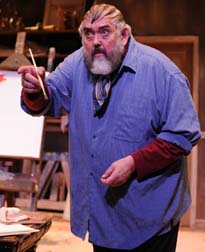

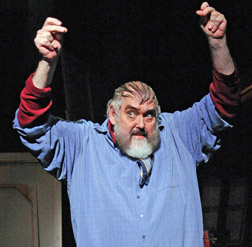

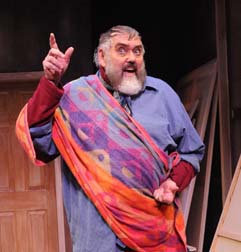

Jim Brochu’s one-man show, directed by Piper Laurie, brings him to life, eyes piercing out of a gray-bearded jowly face, recreating his physical presence and attitude, and most importantly his passionate political commitment to honor at a time when theater people and others were selling out their colleagues.

The story Brochu recounts is fascinating, and his performance is riveting. The device is an interview with a New York Times journalist. I don’t want to know your name, Zero snarls. It’s an interview not a relationship. The interview takes place in a studio on West 28th Street, the top floor of a building Zero owned in what was once known as Tin Pan Alley. Zero wears a blue artist’s smock and dabs at a painting. The set creates intimacy at the same time that it highlights a central and not widely known element of Zero’s life.

Zero Mostel was devoted to art. He had no training in theater and became a performer by accident. In the thirties, he was hired by the WPA (Works Progress Administration, for those who don‘t know history) – along with such painters as Jackson Pollack and Moses Sawyer. Later, he gave art lectures filled with jokes. That led him in 1941 to appearances at the night club, Café Society, in Greenwich Village. He was wildly funny, on stage and off. He was manic. He got people helpless with laughter. Some of that comes through in Brochu’s performance.

But most of the stage story is political. Zero was a Marxist. Brochu/Zero says that Anybody with half a brain was, because of what was going on in Europe: fascism.

That made him a target of the House Un-American Activities Committee’s crusade against free speech in 1955. Are you a communist? he was asked at a hearing. Well, you certainly don‘t beat around the borscht belt, do you? No, I am not a communist, Zero replied.

Are you in favor of the violent overthrow of the government?, he was asked, in a question that violated the First Amendment protection of free speech, not to mention thought.

Zero replied, and the text is from his testimony, Well, sir, as our fourth president, James Madison, for whom they named a lovely hotel on Collins Avenue in Miami Beach once said, “I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by silent and gradual encroachments by those in power rather than by violent and sudden usurpations.

Zero and a handful of artists stood up to the Committee. But the people who ran Broadway and Hollywood were men of little courage. Zero was blacklisted, along with prominent actors such as Lee Grant, Burgess Meredith and Jack Gilford. He excoriates those who named names: the director Elia Kazan, the actor Lee J. Cobb, the choreographer Jerome Robbins.

Zero says, Robbins only went to communist meetings to make connections; to further his career. Hell, he would have joined the Girl Scouts if they let him choreograph a number. He was so weak. And they go after the weak ones you know. He named us to save himself….Why were they targeting actors, he wondered. What did they think we were doing – giving acting secrets to the enemy?

Zero tells how the Committee targeted actors and Jews. He declared, That committee of lily-white Protestants marched us in front their firing squad of fear and pulled the trigger on our lives and our work. It was an intellectual final solution to eliminate thought; they couldn‘t kill our bodies – they had done a damn fine job of that already – so they decided to obliterate our minds. And they targeted Jewish minds.

Zero tells the appalling story of Phil Loeb, the actor who played Jake on the TV serial, The Goldbergs. He recounts, He lived his life practicing the greatest principal of America – that all people were created equal and should be treated that way. Even actors.

Outrageous! Do you know what his “Un-American activities” were? He was fighting for black actors to be able to use the same stage door as white actors, he was fighting for equal pay for men and women, paid rehearsal time, hot running water in dressing rooms. Horrible! Despicable!

So the Committee subpoenaed him and they blacklisted him and they destroyed him and then all of America sat back and said, “Of course he shouldn‘t work. He‘s evil. He‘s the Jewish devil!” And the man lost everything. And Kate and I took him in and he lived with us. We cared for him. We fed him and we clothed him and then we watched him disintegrate.

So one morning, Kate made him breakfast, he put on his coat, he said bye-bye, checked into the Taft Hotel and jumped out the window.

Later, Burgess Meredith found a tenement on the lower East side, turned it into a theater, and starred Zero as James Joyce’s hero Leopold Bloom in Ulysses in Nighttown. The play was memorable, and Zero was so good that producer David Merrick called him to do a Broadway play, The Good Soup. But tragedy struck in 1960, during rehearsals for that play, when Zero’s leg was crushed by a bus that careened out of control on an icy street. The leg was saved, but he would endure frequent pain thereafter.

Still, he continued on the stage and was a triumph in Rhinoceros, the absurdist play by Eug¨ne Ionesco. It had resonance for him: It‘s about conformity. It‘s about not becoming a Berkeley [a prominent informer] or a Robbins. It‘s about being true to yourself, he says. Zero virtually morphed from a man into a snorting rhinoceros, mesmerizing audiences and critics.

His next triumph was full of irony. The show doctor brought in to fix A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which would be a smash hit, was Jerome Robbins. The producer asked, “Will you work with him?” Zero said, “Of course I‘ll work with him. We of the left do not blacklist.”

But he wasn’t forgiving. He welcomed Robbins: “Hiya, Loose Lips. How ya been? Haven‘t seen you since 1953 when you gave all those names to the Committee. You haven‘t aged very well, Mr. Robbins. Sleeping poorly from a bad conscience? Did you say hello to Jack Gilford over there. Say hello to Jack. You remember Jack – whose wife‘s career you destroyed.

No, don‘t apologize, Mr. Robbins. What do you have to apologize for? You‘re a hero. You saved America with your testimony. They‘ll give you a state funeral when you die. But you won‘t be able to be buried in hallowed ground, did you know that? Because the Torah says that informers can‘t be buried in sacred ground. Your soul is going to twist and turn forever in the limbo of your dishonor and your spirit will roam the earth for all eternity like a golem. Like a feared and hated golem.” (Then, all smiles) Now, shall we do the opening number?

Zero’s triumph was complete in 1964 when he played Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. The next year, he got an invitation to a state dinner hosted by President Lyndon Johnson.

This is a fascinating and important play, not only for its dramatic heft, but for the story it tells about America’s dark days of ideological repression.

Zero Hour. Written and performed by Jim Brochu; directed by Piper Laurie. Peccadillo Theater Company at Theatre at St. Clement’s, 423 West 46th Street, New York City. 212-239-6200. Opened November 22, 2009; closes January 31, 2010.

Continues from March 7th at DR2 Theatre, 103 East 15th Street.

Great review — so glad to know this show exists. Your website is excellent, very user -friendly. I could print off this piece very easily, which practically never happens on other websites. You are a wonderful publisher of all kinds of genuine news, no Huffington-fluff — an exception in the blogosphere.

Cheers,

Jane