By Lucy Komisar

In 1960, I was among a handful of college students who volunteered at the 125th Street offices of “The Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South.” The sit-ins had started, southern sheriffs were brutalizing protesters, and King had been arrested and would be released on the intervention of President Kennedy.

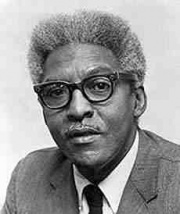

The committee had been organized in Harry Belafonte’s New York apartment and was run by Bayard Rustin, a pacifist and King‘s leading strategist. One of the “older” activist volunteers was Michael Harrington, 33, a writer who used his pen to help the campaign. Rustin was also the lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, which I attended.

So, it was with special interest that I saw “The Great Society,” a play about Lyndon Johnson‘s attempt from 1963 to 68 to deal with the defining crises of his presidency, the civil rights movement at home and the war in Vietnam. One of the characters in the play is Bayard Rustin. The work‘s author is Alexander Harrington, Michael‘s son. (Both Rustin and the older Harrington died in the late 1980s.)

The leitmotif of this fascinating drama is that Johnson‘s good intentions were hog-tied by politics, an appropriate ranch metaphor for this giant of a Texan. Johnson who had the typical macho fear of taking actions that might make him look “soft.” Specifically, that if he didn‘t follow his most hawkish advisors and escalate the war in Vietnam, he would appear weak and be vulnerable to criticism by Republicans, particularly Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, expected to be a presidential challenger in 1964.

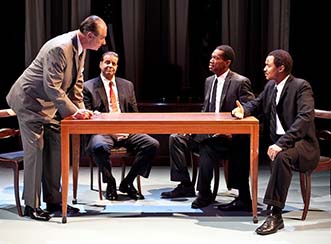

In Harrington‘s play, we see Johnson (Mitch Tebo) in the Oval Office. Tebo is a very good, edgy Johnson, with glowering looks that can blow people away, though I would have liked more of a Texas accent.

Most of the time, he meets with members of his government, the Congress and visitors in the Oval Office. In one scene, he and a senator are in bathrobes having gone skinny-dipping in the White House pool. In another, Johnson, sitting on the toilet, talks to Attorney General Nicolas Katzenbach. That famous image elicited a few nervous giggles from the audience.

At various times he meets with Hubert Humphrey (Charles F. Wagner IV), senator from Minnesota, who became Johnson‘s vice-president, a once noble and sad figure who gave up principles for ambition and was nevertheless humiliated by Johnson. Wagner makes him appear always perturbed, as well he must have been. And there is the hawkish Defense Secretary Robert McNamara (Reed Armstrong, a perfect McNamara to the ends of his slicked back hair).

He also meets with Georgia Sen. Richard Russell (Yaakov Sullivan), a Dixiecrat, i.e. a racist Southern Democrat, and Republican Sen. Everett Dirksen (Robert Ierardi), the GOP minority leader, who supported his Vietnam policy, as well as with Arkansas Sen. J. William Fulbright (James Lurie) who was chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and Oregon Sen. Wayne Morse (Mac Brydon), both Democrats who opposed it. Fulbright, a fellow Southerner, accuses Johnson of selling out to the hawks.

Elena McGhee as Lady Bird is a very smart Southern charmer, very incisive and very supportive of a guy who occasionally showed his insecurities.

Seth Duerr‘s direction is strong and realistic, almost cinematic.

Harrington has constructed the dialogue from published texts. However, he acknowledges in the playbill that sometimes, for the sake of the drama, he has composited events. He has put people at meetings they didn‘t attend and put words in the mouths of individuals who didn‘t say them. He believes he was faithful to the characters‘ views except for one case where, he said, “It is possible walk away from [one] scene with a misinterpretation of McNamara‘s views.”

So, although not uncommon in historical dramas, the play tells a story that is generally accurate but not always specifically accurate. It‘s a small quibble in the context of the overall truth of the production.

Some comments are surprising. Russell, the conservative, says to McNamara, about North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, “They call him ˜Uncle Ho.‘ Bob, you can‘t beat an enemy the people think is their damn uncle.”

The civil rights part of the Johnson drama focuses on his dealings with King and Rustin. They come to the Oval Office calling on the President to pass the Voting Rights Act. He demurs, thinking that after Congress has just passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it isn‘t the time to press the legislators for more.

He is also angry at the Mississippi Freedom Democrats‘ challenge to the white state delegation at the 1964 Democratic convention. (I went to Atlantic City to report on the challenge and thought it a brilliant political move.)

Then in March 1965, the Selma to Montgomery march takes place, it is attacked by the thuggish troops of Gov. George Wallace, and white sympathizer Viola Liuzzo is shot dead. The Voting Rights Act gets passed.

Harrington is sympathetic to Johnson, who he shows telling Fulbright that he wants to get Vietnam out of the way so he can finish the job Roosevelt started. Indeed, it was Johnson who gave us Medicare and Medicaid. Harrington shows Johnson‘s resentment at the liberals who loved Jack and Bobby Kennedy in spite of the fact that they were middle-of-the-roaders. He wants people to love him as they loved FDR.

It‘s amusing to see the interaction between Congressmen, how Russell and Strom Thurmond suck up to each other. There‘s also a lot of bloviating. (Plus §a change.)

And it‘s enlightening to learn how Johnson had been willing to accept a deal that would have eliminated public accommodations from the Civil Rights Act. But on voting rights, he gets tough. He hovers over Dirksen, ordering him to support the bill.

Johnson gets angry as King becomes a critic of the war. In a riveting scene, Johnson tries to persuade him not to give an anti-war speech in New York City to Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam. Tebo shows Johnson twisted in fury at this “betrayal” by someone whose civil rights goals he had supported.

Viewers might be surprised that Rustin also urges King not to make the speech. But as Harrington knew, Rustin‘s opposition to driving a wedge between the civil rights movement and the labor movement, whose key leaders were supporting the war, made him part of a faction that split the Socialist Party. The anti-war faction was led by Michael Harrington.

Johnson‘s machismo made him view the war as a personal contest, and that would do him in. He tells Lady Bird, “If I were to withdraw, the communists will overrun South Vietnam, and people‘ll say LBJ turned tail and handed America its first defeat.” But Harrington also has him distraught, thinking about a sergeant attached to the White House who has six kids in the military.

More clear-headed, the Southern Democrat Russell tells him, “Mr. President, you are — you‘re talking about bombing the military facilities of a sovereign nation.” And, supporting the view of Wayne Morse, Russell says, “Electoral politics has no place in a discussion of national security.” (Among my few quibbles is that Mac Brydon‘s Morse is too intemperate.”)

Harrington wants to persuade us that Johnson wanted to do the right thing, but didn’t have the courage to take the political fall-out of winding down the war. Still, the military policy in Vietnam was his call. Consumed by the fear of seeming week, Johnson accepts McNamara‘s policy of escalation and attacks the critical Humphrey for his “treachery.” He orders “Operation Rolling Thunder” to bomb North Vietnam. According to the CIA, the 44 month bombing campaign killed 90,000 Vietnamese, including 72,000 civilians. More than 800 U.S. airmen died. The campaign failed in its mission to defeat the North.

The bombing also destroyed Johnson‘s political chances. The anti-war movement was galvanized. We hear voices shouting, “Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Johnson’s dramatic announcement that he would not run again for President was their victory.

Harrington uses real dialogue to construct a dramatic picture that is absorbing for theater audiences and could give students of newer generations a vivid understanding of events fifty years ago that still reverberate.

“The Great Society.” Written by Alexander Harrington; directed by Seth Duerr. Clurman Theater, 410 West 42nd Street, New York City. (212) 239-6200; 800-432-7250. Opened Aug 8, 2013; closes Aug 24, 2013. 8/19/13.

Well, it’s all about to be repeated, in different color perhaps, like black for white… Supreme Leader Obama getting about starting to bomb Syria (back to the Stone Age, of course) under a false flag, with the American people consent, or at most, their total indifference, what have we ever learned ?

Kind regards,

Dom