By Lucy Komisar

I was having dinner at the Moscow apartment of Tatiana Kudryavtseva, the Russian translator of books by Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, Norman Mailer, John Updike and William Styron, among others. But it wasn’t a literary evening. The other guest was Rufina Philby,  widow of the British spy. Tatiana knew her through Greene, who had written a preface to Philby’s memoir.

widow of the British spy. Tatiana knew her through Greene, who had written a preface to Philby’s memoir.

Rufina, or Rutchka, as Tatiana called her, is a striking woman in her 60s, her short, brown hair glistening from a reddish tint. She was disarming, referring to Kim as the spy and recounting how they’d met in Moscow when a friend couldn’t use a ticket to the U.S. Ice Capades.  The couple going with her invited Kim. She recalled how depressed he’d been in his Russian exile until the KGB finally gave him a job–training spies to behave as proper Brits so they’d pass easily in England.

The couple going with her invited Kim. She recalled how depressed he’d been in his Russian exile until the KGB finally gave him a job–training spies to behave as proper Brits so they’d pass easily in England.

I asked if she’d been to the KGB Museum I’d heard about.

I’ve never been there, she said. I don’t know anything about it. I didn’t know there was one.

If I arrange it, will you go with me? I asked. Yes, just let me know, she replied, giving me her phone numbers for Moscow and the dacha.

The museum is at Bolshaya Lubyanka 12 in a sandstone-colored building with columns and round windows a block north of the massive headquarters of the KGB, now FSB (Federal Security Service). It’s run by the FSB public relations office. Patterns of secrecy die hard. There’s no sign on the building.

Museum? What museum?

When I opened the door, a woman in a military uniform blocked the way. She said she had no information about the museum, but finally acknowledged that it was there and that I could visit with a tour. She didn’t know where to book a tour or who to call. Finally, a man appeared in the entranceway and provided that information.

Patriarshy Dom Tours, the name I was given, runs visits twice a month. (One can’t go alone, only through a tour company.) Rufina confirmed the date I chose, and I booked via e-mail, giving our names and identifying myself as a journalist. When I phoned to confirm, the travel agent told me, They don’t like journalists. And they don’t like your taking Mrs. Philby. A few days later, Rufina called and said she was so sorry; she’d forgotten an appointment for that day.

On the chosen morning, I joined 18 people from places as disparate as Jamaica, Mauritius, Ireland, England, France, Germany and the U.S. outside the Sidmoy Kontinent supermarket on the corner of Bolshaya Lubyanka. Speaking English, the guide, Anna, directed, No photos.

Ireland, England, France, Germany and the U.S. outside the Sidmoy Kontinent supermarket on the corner of Bolshaya Lubyanka. Speaking English, the guide, Anna, directed, No photos.

It’s finished, I said, indicating there was no film in my camera. That’s a KGB trick, retorted Anna.

She would translate for the FSB official, Valery, who said proudly he’d been in the service 25 years. He wouldn’t give his last name.

The museum, which includes 2,000 exhibits in four rooms, was opened in 1984 by KGB chairman Yury Andropov, who led the agency for 15 years. Initially it was just for KGB employees, not even for spouses and children. I couldn’t think of a time when we would admit foreigners; now, we invite colleagues from different security services, mused Valery.

For the next two hours, Valery gave us a detailed  account of the exhibits, moving along displays of photos and letters, uniforms and spy paraphernalia. There was no little revisionism and subtle gloating at the KGB’s successes over the West.

account of the exhibits, moving along displays of photos and letters, uniforms and spy paraphernalia. There was no little revisionism and subtle gloating at the KGB’s successes over the West.

We got some new spins on the agency’s old leaders. Valery informed us that founder Felix Derzhinsky supported the market economy. The museum shows his study with a wood desk Valery said was built by a U.S.-Russian pre-revolutionary joint venture.

Valery described the Stalin purges of the ’30s not as a time of KGB brutality but of KGB suffering. Thirty thousand of our agents were exterminated, every third man, our best people, said Valery, those who didn’t want to participate in purges.

As he pointed out the displays of captured spies, Valery expressed satisfaction at the KGB’s besting of the West.

Valery pointed to a photo of a tapestry presented by children to U.S. Ambassador Averill Harriman in 1945 and kept in his embassy study. It featured an eagle whose mouth was bugged.

Martha Peterson, U.S. cultural affairs attaché,  was caught putting a container with money and a miniature camera into a niche cut in a bridge. The photo shows her being arrested.

was caught putting a container with money and a miniature camera into a niche cut in a bridge. The photo shows her being arrested.

Double agent Oleg Penkovskiy, who worked for Soviet military intelligence, used a Minox camera to photograph secret documents for the Americans and British. The cameras are shown along with the drop box he left behind a heater in a building entrance hall. A Soviet photo catches a U.S. diplomat collecting the film.

There were exhibits from the rare moments of alliance. One display told of a failed assassination plot that targeted Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Teheran Conference in 1943; Nazi agents were arrested.

Then there were displays to honor the Soviet agents who were caught. Atomic secrets spy Klaus Fuchs was detected in England in 1949, sentenced to 14 years and released after 9. Valery noted with relief, In the U.S., he would have gotten the electric chair.

Soviet spy Rudolph Abel was arrested in 1957 and exchanged for American Gary Powers, whose spy aircraft was shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960. Both men apparently had an artistic bent. A book of fine paintings by Abel is for sale. A bit of a rug Powers made in prison from potato sacks was donated by his son.

And of course, there’s Kim Philby, the Third Man of British Intelligence, who was part  of the illustrious Cambridge group. Photos show Kim, his book and other mementos, including one of those elaborate medals that officials like to pin on each other. I understand that his wife, Rufina, lives in Moscow. Has she seen this exhibit? I inquired.

of the illustrious Cambridge group. Photos show Kim, his book and other mementos, including one of those elaborate medals that officials like to pin on each other. I understand that his wife, Rufina, lives in Moscow. Has she seen this exhibit? I inquired.

Oh, yes, Valery replied. She’s visited the museum. She brought us this book (‘My Secret War’) and his Order of People’s Friendship.

Hmmm.

The most fun was the gear used by foreign agents on both sides. One display showed real and counterfeit Soviet passports. Staples in USSR passports corroded, while the U.S. used stainless steel. Valery said hundreds of American agents were caught, because their phony passports had the wrong staples.

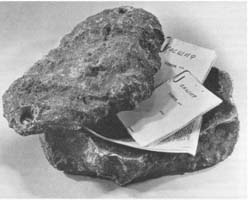

There are numerous displays of secret containers, planks of wood and tubes and false rocks. A photo shot from a rubbish container where a photographer waited for two days shows an American spy sticking his arm out of a car and throwing a piece of wood into the forest. A log stump that covered a silver and glass device, was used by U.S. intelligence to retrieve information about nearby missile testing. An American tape recorder ensconced in a tree branch was set near a military airport.

planks of wood and tubes and false rocks. A photo shot from a rubbish container where a photographer waited for two days shows an American spy sticking his arm out of a car and throwing a piece of wood into the forest. A log stump that covered a silver and glass device, was used by U.S. intelligence to retrieve information about nearby missile testing. An American tape recorder ensconced in a tree branch was set near a military airport.  A suitcase with equipment to send encrypted messages via satellite was found with Gary Powers. It had a small bottle of poison hidden in a false bottom. Of course, there were cameras in watches and cigarette lighters and deceptive soap, cigarette packs and soda cans.

A suitcase with equipment to send encrypted messages via satellite was found with Gary Powers. It had a small bottle of poison hidden in a false bottom. Of course, there were cameras in watches and cigarette lighters and deceptive soap, cigarette packs and soda cans.

After our tour, I called Tatiana to tell her about the conflict between Rufina’s story and what Valery had said about her visit. She replied instinctively, Maybe the KGB is lying.

IF YOU GO

Patriarshy Dom Tours runs visits to the museum. In the U.S.: phone/fax 650-678-7076; e-mail pd*****@***oo.com. In Moscow: phone/fax 095-795-0927. Valery said tours also are available from Intourist, Interservice and Nikatour.

First published by The Chicago Tribune and The Toronto Star.

interesting bits of history. our secrets are still hidden by bush, bush and co-conspirators.

As a historian, I find much to criticize in American declassification policy. That said, It is simply incorrect to suggest that the Soviet/Russian record on declassifying intelligence history is better than the American one.

Since the 1970s, the Freedom of Information Act has brought about the release of a great deal of information. In addition, the various intelligence agencies, notably the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency have robust declassification programs, releasing both to the National Archives and the web great volumes of intelligence documents. (Note, for instance, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Corona, and Venona releases.)

These efforts continued during the Bush Administration. (E.g. declassification of SIGINT pertaining to the attack on the Liberty, NSA’s official history of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, release of the CIA’s “Family Jewels,” releases of intelligence estimates on China and Vietnam, release of once very sensitive HUMINT reporting on the Warsaw Pact, etc.) There are almost no American WWII-era intelligence records that are still classified. Compare this to Soviet KGB and GRU records from that era which are mostly still secret.

It is also worth noting that there are two major museums in the United States devoted to intelligence and open to the public. One is the National Cryptologic Museum, associated with the National Security Agency and the other is the International Spy Museum. (Full disclosure: I am the Historian at the latter.)

LK: There’s nothing in the article that says the Russians are better at declassifying intelligence than the Americans. I look forward to visiting the International Spy Museum.

Interesting story about TRIGON. I just saw a documentary about it. In USSR they made a movie based on this story “Tass Upolnomochen Zayavit”…

reminds me of a recent spy scandal when the Russian agent was exposed… secret services of both countries are doing pretty good job…