Seeing the best and worst of German character & history

By Lucy Komisar

Weimar and its surroundings represent the best and the worst of the German character and history. On the square is the neoclassical German National Theater, with a statue of poet Johann Goethe (who founded the theater) and his contemporary, dramatist Friedrich Schiller. They were part of the “Sturm und Drang” (storm and stress movement, which advocated a celebration of nature and emotion.

On the day I visited, a group of theatrical activists in red and white robes were performing alongside the statue, handing passers-by advice cards labeled “Secret Agent: freedom training.” Considering what we would soon see, it was an appropriate idea.

About 30 minutes north of the city – which also politically conjures up the failed government of the Weimar Republic – is Buchenwald, the concentration camp that stands as a memorial to the victims of the Nazis who destroyed the Republic.

And 74 miles northeast is Leipzig, where after the fall of communism, the local citizens founded their own museum to detail the human rights violations of the Stasi (pronounced shtah-zy), the nickname of the communist secret police, literally the state security organization, Sta from “staat” (state) and si from “sicherheit” (security).

Beginning with the good part, we visited Goethe‘s house in the center of town, seeing the rooms where he wrote, viewing even the old carriage he rode in. We walked in the park along the Ilm River to see the garden house where he wrote in summer. Goethe benefited from living in an era when rich patrons of the arts adopted writers and poets!

Weimar is peaceful, charming, almost a living museum. The town is small and you can meander through it in a horse carriage. Not far from the theater is house of Schiller, where he wrote “William Tell.” Also on the square is a stunning museum commemorating Weimar as the founding site of Bauhaus art and architecture. The Bauhaus movement was not only avant garde, but had many Jewish participants, and the Nazis destroyed it and killed the participants that couldn‘t flee.

To see of that period, we drove 6 miles to the north. Buchenwald is on all the tourists‘ maps and is well sign-posted from the city.

Buchenwald

I have been to Buchenwald twice, and each time it was appropriately gray and drizzly. There were not a lot of people there. Among the visitors you see are groups of German high school students; this trip is required instruction. Germany‘s remembrance of Nazi war crimes is quite different from the policy of Japan.The government has approved history textbooks which whitewash Japanese wartime atrocities which rivaled the Germans‘ in spirit if not numbers.

When you arrive at Buchenwald, you walk through a gate constructed in a long, low stone building – arrest cells and SS administrators‘ offices — topped by a wooden structure which was the main watchtower. At the top of the structure is a clock stopped at 3:15, the hour of liberation. The Germans had a bizarre habit of inscribing ironic slogans on their concentration camp gates. The one in Auschwitz says “Arbeit Macht Frei” – “Work Makes You Free.” Buchenwald‘s sinister slogan was “To Each His Own.”

Walking around the grounds, you can see the camp fence and watchtowers, the large mustering ground where inmates had to line up in morning and evening to be counted – or to be punished or executed. There are memorial stones to individual and groups of victims such as the gypsies. Many are decked with flowers left by visitors. More flowers are inside, in the arrest cells, in a cellar used for executions and storage of dead bodies, and at the crematorium ovens, for me the most stunning site.

Buchenwald has been open as a memorial since September 1958. The camp was in the post-war Communist zone, and the new GDR government tore down some of the buildings. Plaques and exhibits emphasized the Communist resistance to fascism. They ignored the fact that a section of the camp was later used for internments by the Soviets.

After German reunification, control passed to the former West German government, and new plans were made for the memorial. In 1995, the large storehouse was turned into a museum to portray in minute detail the daily lives and suffering of the prisoners. Exhibits show barracks life and abuse, inmates‘ attempts at survival and resistance, and mass deaths. The photographs and artifacts are chilling.

But even more horrifying is a section at the end which tells what happened to the SS chiefs responsible for the camp. A few were executed; most were sentenced to decades of imprisonment. And then a few years later, by the early 50s, at the height of the Cold War, most of the jailed SS criminals were freed by the West Germans!

Stasi

One can‘t compare evils. The East German Communists did not commit crimes on a par with the Nazis, but they belong in the pantheon of German political terrorism. At Leipzig, which was a center of anti-communist resistance by left activists, we visited the museum that citizens created when the Berlin Wall was knocked down and ended communist rule. The small museum, called “Stasi: Power and Banality,” shows not only the tools of oppression: rifles, barbed wire, and the “spook” spying technology – even cabinets of disguises — that helped the Stasi secret police keep the whole country under surveillance.

It also commemorates the popular resistance. Wall charts recount the peaceful revolution which began with a demonstration in January 1989 to mark the 70th anniversary of the murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg, democratic socialists killed by the right. They also document the ballot rigging at the local elections in May, an environmental demonstration in June, and a mass demonstration October 9, 1989, which passed by the Runde Ecke, then the Stasi‘s district headquarters.

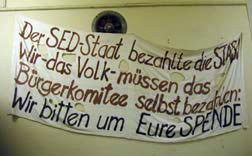

A hand-lettered banner that probably hung out of a window says, “The SED [Socialist Unity Party of Germany] state pays for the Stasi. We – the people— must pay for the Citizens Committee ourselves. We ask for your contributions.” On December 4, members of the public occupied the Runde Ecke, set up a Citizens Committee which stopped the Stasi file shredding and took control of the building. The exhibit opened in 1990 and has been visited by thousands of people.

We stayed at the Weimar Hilton, perfectly located not just for seeing Weimar and Buchenwald, and for visiting Erfurt 17 miles west, but a good jumping off point for Leipzig, which we toured on the way to Berlin. The Hilton is across the street from the Goethe‘s favorite Ilm Park. We had a large room with Hilton‘s typical business-friendly wrap-around-desk, multiple power outlets, several phone ports, and a choice of internet connections: wifi for your own computer or a TV with akeyboard to get you online.

At breakfast there was a superb buffet in a restaurant with Chinese lacquer screens. One fascinating innovation was orange cards set at each dish informing you by color coding which were low fat and low calorie, low cholesterol, high-energy and high fiber. Diners can sit out on the terrace or visit the beer garden set outside among trees. For more relaxation, there is a swimming pool and hot tub. It all provides a welcome calm in the midst of the turmoil portrayed in the surroundings.

Hilton Weimar

Belvederer Allee 25

D-99425 Weimar

Germany

Hi***********@t-******.de

Tel 49 (0) 3643 772 0

Fax 49 (0) 3643 722 741

1 800 Hiltons

Goethe House

Frauenplan 1

Weimar

49 (0)3643 545300

Summer Tues to Sun, 9 to 6

Winter Tues to Sun, 9 to 4

Entrance 6 Euros ($7.40), discounts seniors & youth

Schillerhaus

Schillerstrasse 12

Weimar

49 (0)3643 535450

Apr-Oct, Wed-Mon, 9 to 6

Nov-Mar, Wed-Mon, 9 to 4

Entrance 3.50 Euros ($4.30), discounts seniors & youth

Bauhaus Museum

Theaterplatz

99423 Weimar

49 (0)3643 546161

April-Oct,Tues-Sun, 10 to 6,

Nov to March, Tues-Sun,10 to 4,

in**@ku********************.de

Tourist information

Markt 10

99423 Weimar

49 (0)3642 240000

Mon-Fri 9:30 to 6, Sat & Sun, 9:30 to 3

To**********@we****.de

Buchenwald Memorial

D-99427 Weimar-Buchenwald

49 (0)3643 430200

Group guided tour requests fax 49 (0)3643 430102

bu********@bu*******.de

Inside exhibits and museum:

Apr-Oct, Tues-Sun, 10 to 6 (last entry 5:30)

Nov-Mar, Tues-Sun, 10 to 4 (last entry 3:30)

Outdoor installations open daily till nightfall

Suggested visit lasts 3 hours. Seeing everything could take all day.

Entrance free

From Goetheplatz or main RR station, Weimar, bus #6 (not bus marked Ettersburg)

Stasi Museum

Museum in der Runden Ecke (at the Round Corner)

Bürgerkomitee Leipzig e.V. für die Auflösung der ehemaligen Staatssicherheit (MfS)

Dittrichring 24

Postfach 10 03 45

D-04003 Leipzig

Tel 49 (0)341 961 2443

Fax 49 (0)341 961 2499

ma**@ru****************.de

Ask for the “Tour through the museum” guide in English.

On Sundays at 2 pm, there is a tour in German to the places that marked key events in the 1989 movement against the Communists. It starts at the main entrance to the Nikolaikirche (Nicholas Church); tour price 3 Euros ($3.70). Other tour dates for groups can be arranged.

The best guidebooks:

Germany, DK Eyewitness Travel Guides, $30

This takes you to each town and village and bullets key sites, with mini- on each page and the opening times, costs and other relevant information. Major museums and sites get diagrams, with more details about the key attractions. Suggested hotels and restaurants. Good regional and local maps.

Germany, Insight Guides, Langenscheidt Publishers, $23.95

This offers more detail about the history, art and economy as it moves through the towns and regions in a narrative style. Suggested hotels and restaurants. Good regional and local maps.