By Lucy Komisar

NEW YORK, July 5 (IPS) – The United States is famous as a country that denies the validity of class. But you’d get a different idea at theaters across New York, where two new plays and a revival look head-on at the way wealth, status and power affect people’s lives.

The new original works are Radio Golf and In The Heights, while the revival is A Moon for the Misbegotten. They’re either on Broadway or moving there shortly.

The first two examine class through the prism race or ethnicity. Radio Golf is the last of the late August Wilson’s plays about a black neighborhood in Pittsburgh in each decade of the 20th century. Here class doesn’t just separate blacks and whites, it divides African Americans as well. It’s 1997, and Harmond Wilks (Harry Lennix), a young up-and-coming black man, the son of a wealthy realtor, is making a run for mayor.

He and his friends are part of the new black middle class. His wife Mame (Tonya Pinkins) is about to get a job as press secretary to the governor. His friend Roosevelt Hicks (James A. Williams) works at a bank but sees his future in bigger things. Hicks cultivates powerful whites. Golf, a game of the rich and upper middle class, becomes a symbol of where Roosevelt wants to be.

In a broken down black neighborhood, next to a storefront Harmond is using for his campaign, you see abandoned shops full of debris, symbols of a community destroyed. Roosevelt tacks a poster of millionaire golf champion Tiger Woods on the storefront wall. Harmond puts up one of Martin Luther King Jr. The two men’s heroes are clearly different.

On the other side of the class divide are Sterling Johnson (John Earl Jelks), who has spent time in jail for bank robbery and ekes out a living doing small painting and construction jobs. He says he is looking for Christians – i.e., people with charity in their souls. Elder Joseph Barlow (Anthony Chisholm), cynical, outspoken, his face in a permanent scowl, has a claim on the house that the Wilks-Hicks project would destroy. Barlow is the real hero of the play, the underclass guardian of family and community. This is about the strivers who would get out of the ghetto, move up, and sometimes turn their backs on moral obligations to those left behind. The dilemma is: will Harmond press ahead with a project to build a 10-story apartment building for the middle class even if it wipes out homes where poor blacks have lived for generations?

On the other side of the class divide are Sterling Johnson (John Earl Jelks), who has spent time in jail for bank robbery and ekes out a living doing small painting and construction jobs. He says he is looking for Christians – i.e., people with charity in their souls. Elder Joseph Barlow (Anthony Chisholm), cynical, outspoken, his face in a permanent scowl, has a claim on the house that the Wilks-Hicks project would destroy. Barlow is the real hero of the play, the underclass guardian of family and community. This is about the strivers who would get out of the ghetto, move up, and sometimes turn their backs on moral obligations to those left behind. The dilemma is: will Harmond press ahead with a project to build a 10-story apartment building for the middle class even if it wipes out homes where poor blacks have lived for generations?

Harmond moves between both sides. He wants to be mayor, and he wants to build the high-rise. But he annoys Mame by refusing to forget about a policeman who killed a black man. Will Harmond forget and betray the underclass of his community? It’s the question that Wilson, who died in 2005, leaves for middle and upper class blacks to ponder about themselves.

In The Heights takes the same conflict of making it vs. commitment to community to Latinos in America. How do those who move up into the middle class relate to those left behind? The story was developed by Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the music and lyrics to a script by Quiara Alegria Hudes. They portray a different dynamic than Wilson did. Here, everyone is a striver.

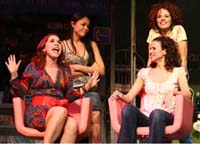

Washington Heights is a neighborhood in upper Manhattan that immigrants from Puerto Rican, Cuba and the Dominican Republic have transformed into a Latino barrio. The play’s setting is a line of tenements and shops — a bodega (Hispanic food shop) and a hair salon  and, then, links to the rest of the city and the country — a car service, an entrance to the subway (the metro), and the lights blinking on a tower of the George Washington Bridge that takes drivers over the Hudson River to the West.

and, then, links to the rest of the city and the country — a car service, an entrance to the subway (the metro), and the lights blinking on a tower of the George Washington Bridge that takes drivers over the Hudson River to the West.

Nina (Mandy Gonzalez) has come back from her first year at Stanford, an exclusive and expensive university in California. But she is conflicted about being at school when it’s costing her parents so much, and she misses the barrio. Unlike Mame and Roosevelt who want to leave their people behind, she wants to stay connected.

So she drops a bombshell: she’s quit Stanford. She’ll go to a local college. Nina’s dad, whose own father was a sugar cane farmer in Cuba, is furious. He’s run a private taxi service since 1986, but his storefront still bears a sign saying O’Hanrahan’s, from the time when Irish immigrants had it. When new Hispanic immigrants are rising from poverty to the middle class, they are doing what other immigrants did before.

They won’t all rise. The working class people in The Heights feel stuck there. Representing them, Vanessa (Karen Olivo), who works in the hair salon, aches to get out. Or they dream about striking it rich in the lottery. Fortunate Nina has a way out. That is emphasized when we see her moment-in-time relationship with Benny (Christopher Jackson), the charming working-class boyfriend who she will leave behind in the sweepstakes for success. Nina’s connection to her community doesn’t stop her from finally returning to Stanford. But it’s also clear she’ll keep her connections.

Those two plays are about the present. There was a lot less mobility, little question of moving up, near the beginning of the last century, especially for women. A Moon for the Misbegotten, written by American master Eugene O’Neill in 1943, is a sharp political commentary about class, money and gender. It depicts a smart woman trapped in a poverty that offers no escape. It is 1923.  The 30-ish Josie Hogan (Eve Best) is helping her self-involved father Paul (Colm Meaney) scrape survival out of a hard scrabble Connecticut farm. Her brother has just taken off for better parts. As a woman, she can’t so easily escape.

The 30-ish Josie Hogan (Eve Best) is helping her self-involved father Paul (Colm Meaney) scrape survival out of a hard scrabble Connecticut farm. Her brother has just taken off for better parts. As a woman, she can’t so easily escape.

Josie and Paul see their way out as Jim Tyrone (Kevin Spacey), a rich, alcoholic, third-rate actor whose inheritance makes him the Hogans’ landlord. They are all of Irish extraction, but the Hogans’ Irish accents — as opposed to Tyrone’s good English — set them a class apart. Jim Tyrone perhaps for want of something better to do visits Josie. Can she catch him? According to her father’s plan to get the farm? For herself to get a husband? Josie is trapped between two largely useless men.

The cards are really held by T. Stedman Harder (Billy Carter), the owner of a neighboring estate, who is defined by his pretentious first initial and his position as an executive with Standard Oil. Paul carries out class conflict by letting his pigs into Harder’s ice pond, which infuriates the oil man. It’s a pyrrhic victory. Harder has the money to buy their place from Tyrone and evict them into the underclass, to a situation that O’Neill leaves to our imagination.

These productions about the class divisions of race, ethnicity and wealth — produced on New York main stages, not in fringe theatres — show that U.S. playwrights, directors and audiences find those themes important — and that the immorality of class power is something they care about.