By Lucy Komisar

Aug 12, 2008

In a year when race is an undercurrent in America‘s presidential election, it is fitting that the smash musical of the Broadway season is “South Pacific,” a play first presented nearly 60 years ago on the theme of intolerance. Based on Tales of the South Pacific by James A. Michener, who served in the region during World War II, the play turns on the anti-Polynesian prejudice of the heroine, young Navy nurse Nellie Forbush (a vibrant Kelli O‘Hara), who is posted to a war-time island base of the U.S. Navy.

While “South Pacific” has been celebrated around the world for its joyous, clever, entertaining musical numbers, and director Bartlett Sher‘s staging is exhilarating, it‘s worth looking at how the show presents its message.

Among the most important American musicals, the play was written by the classic masters of the genre, Richard Rodgers (music), Oscar Hammerstein II (book and lyrics) and Joshua Logan (book). Their goal was to skewer prejudice against Polynesians on the island to deliver a message about racism in general.

The 1949 play is back-dropped by an America warring against fascism that tolerated racism in its own military. Sher subtly points that out by positioning black sailors off to the side, in the background, isolated from the whites who dominate the action.

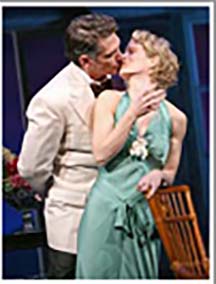

Nellie falls in love with a middle-aged French planter, Emile de Becque (the sophisticated Paulo Szot), but will face a personal crisis when she discovers that he has two Eurasian children from a five-year relationship with a Polynesian woman.

Nellie is white and from the South — Little Rock, Ark, — the city that ironically is iconic for Americans, because in 1957 it blocked black children from attending high school after the Supreme Court in 1954 ruled segregation unconstitutional.

When Nellie complains that her mother is prejudiced — “She makes a big thing out of two people having different backgrounds” — she means mother is against Emile de Becque for being French. Racial bigotry is taken for granted.

The Navy officers want Nellie to check out Emile‘s background, because they‘re considering asking him to sneak behind Japanese lines and report on troop movements. In answer to their question, she replies that he has no children. After she leaves, one of the officers comments, “Well, you don‘t spring a couple of Polynesian kids on a woman right off the bat!”

After a party Emile gives to introduce Nellie to his French friends, she sings, “I hear the human race is falling on its face…” Emile responds: And hasn’t very far to go!” (from “A Cockeyed Optimist.”) Suddenly the children, Ngana (Laurissa Romain) 11, and Jerome (Luka Kain) 8, appear in their nightgowns, followed by the servant, Henry (Helmar Augustus Cooper).

Nellie is enchanted. “Are they Henry’s?” she asks. Emile replies, “They’re mine.”

At first she thinks it‘s a joke. “Oh, of course, they look exactly like you, don‘t they? Where did you hide their mother? Emile: “She’s dead, Nellie.”

Nellie: “She’s—Emile, they are yours!” Emile: “Yes, Nellie, I‘m their father.”

Nellie is shocked “… and ”their mother…was a…was…a…” Emile: “Polynesian and she was beautiful, Nellie, and charming, too.” Nellie: “but you and she….” Nellie departs hurriedly. She breaks off their relationship.

The French planters abuse the local population in their own way, through economic exploitation. Captain Brackett (Skipp Sudduth) tells the comical Luther Billis (Danny Burstein), who hires Polynesians to make souvenirs to sell the sailors: You are causing an economic revolution on this island. These French planters can’t find a native to pick a coconut or milk a cow, because you’re paying them ten times as much to make these ridiculous grass skirts. A local trader nicknamed Bloody Mary by the sailors declares, French planters stingy bastards!

The authors quietly raise questions of American values when the U.S. officers ask Emile to go on the dangerous mission to lick the Japs.” The Americans say, “It‘s as simple as that. We’re against the Japs.” And Emile replies, “I know what you’re against. What are you for?”

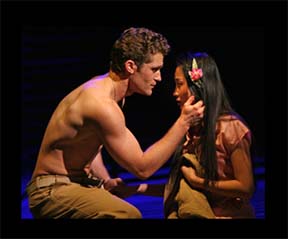

One sailor who has a late conversion is the upper class Lt Joseph Cable (Matthew Morrison). He falls in love with Bloody Mary‘s 17-year-old daughter, Liat (Li Jun Li), but then rejects her as a wife. Joe tells Nellie, I’ve just seen her for the last time, I guess. I love her and yet I just heard myself saying I can’t marry her. What’s the matter with me, Nellie? What kind of guy am I, anyway?

When Emile arrives, Nellie admits she can‘t marry him because of his relationship to the Polynesian mother of his children. She says, “It isn’t as if I could give you a good reason. There is no reason. This is emotional. This is something that is born in me.

In a moving high point of this morality play, Joe declares, “It’s not born in you! It happens after you’re born….” And he sings:

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear,

You’ve got to be taught from year to year,

It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear”

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made,

And people whose skin is a different shade”

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate”

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

Ironically, when Emile helps Joe plan to go behind the lines, he tells him, You will get in touch with my friends, Basile and Inato ”two black men” wonderful hunters. The mission crucial to dislodging the Japanese from the islands depends on two black men!

As this is Broadway à la Hollywood, Nellie, thinking about Emile, suddenly gets an epiphany. She realizes, “I know what counts now. You. All those other things, ”the woman you had before,” her color…. (She laughs bitterly.) What piffle! What a pinhead I was.”

It took Americans another 15 years from then to pass the civil rights act. And, maybe, 60 years from the opening of “South Pacific,” to choose a mixed-race president.

“South Pacific.” Book by Oscar Hammerstein II & Joshua Logan. Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. Music by Richard Rodgers. Directed by Bartlett Sher. Choreography by Christopher Gattelli. Lincoln Center Theater at Vivian Beaumont Theater, 150 West 65th St. 212-239-6200 Running time: 2:50.