By Lucy Komisar

August Wilson’s powerful, moving play conjures up a mood that is both poetic and surreal, though on the face of it, it is completely naturalistic. Perhaps it’s the distance of time, nearly a century ago, 1911, when blacks, only 50 years away from the start of the Civil War, were living on the border between slavery and freedom. Or it could be the ethereal staging by director Bartlett Sher, who excellently follows Wilson’s intent to turn the characters into symbols of their kind as well as real people. Sher starts that by showing the characters first in silhouette.

We are in a Pittsburg boarding house run by Seth Holly (Ernie Hudson) and his wife Bertha (Latanya Richardson Jackson). The action takes place around a long wood dining table encircled by mismatched spindleback chairs. Tomatoes and cabbages struggle to survive in a tiny patch of yard. (Set by Michael Yeargan.)

Seth Holly works at night in a mill and makes pots and pans out of scrap. He is uncompromising and unforgiving in his moral demands that people behave and work and don’t make excuses. But the people who live in boarding houses can’t always meet that standard.

They are all looking for something.

The young Mattie Campbell (Marsha Stephanie Blake) had a lover who deserted her, does ironing now, and is courted by Jeremy Furlow (Andre Holland) who has come up from the south and hopes to make it with his guitar playing. She wants love and security; he wants a good time.

Then there is the mystical Bynum Walker (an avuncular Roger Robinson), a country spiritualist on the track of the shining man who has the secret of life. He helps people to cope. When Mattie pines for her old lover, he gives her a charm to forget. He is known as a conjur man, but he’s really a psychologist and therapist who dispenses common sense.

The high drama is sparked by Herald Loomis (Chad L. Coleman), who has arrived with his daughter Zonia (Amari Rose Leigh) in search of the wife he was separated from in 1901 when Joe Turner, the brother of the governor, seized him and other blacks and forced them to work on his land for seven years.

Turner is based on the real Joe Turney, the brother of a governor of Tennessee, who kidnapped Negroes and forced them into seven years servitude. A morose fellow with a black coat and big brimmed hat, Coleman plays him as a man who seems about to explode from fury.

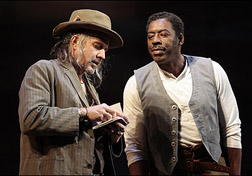

Loomis asks for help from the itinerant peddler, Rutherford Selig (a shrewd Arliss Howard), who sells pots and pans (including those made by Holly) and other household necessities on his route around Pittsburg. Selig makes it his business to find out just who is living where, which feeds his second job as the people finder. It appears that his family made money from blacks in ways that, with some irony, suited the times: his grandfather was a slaver, and his father found runaway slaves for plantations.

The rest of the morality tale is embellished by Molly Cunningham (Aunjanue Ellis), a sexy lady who tells Seth Holly, I likes me some company from time to time, to which he replies, I don’t have no women hauling no men up to rooms to be making their living.

Somehow, their stories are submerged in a common sense of origins when they dance the lively African Juba, a shuffle and stomp which Wilson means to evoke the Ring Shouts of the African slaves. It’s a Christian African fantasy, with references to the Holy Ghost.

People need to know their songs, Bynum tells them. It’s the symbolism of recognizing oneself.

When a man forgets his song he goes in search of it. Wilson’s message is the need for self-discovery and self-knowledge. It’s what binds people together.

The ensemble of actors takes that message to heart, delivering performances that define each character as a distinct individual but also one of a shared community.

Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. Written by August Wilson, Directed by Bartlett Sher. Produced by Lincoln Center Theater. Belasco Theatre, 111 West 44th Street. 212-239-6200. Opened April 16, 2009, Closes June 14, 2009. http://www.lct.org/

Review on NY Theatre-Wire site.