By Lucy Komisar

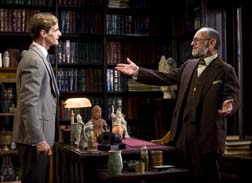

Imagine that you are hidden in a corner of Sigmund Freud’s cozy Hampstead study, with a wall of book shelves, a large window onto the garden and a leather chair next to the iconic couch. It’s 1939, King George speaks on the radio, sirens warn people to extinguish their lights to evade the bombs of the Luftwaffe. Freud (Martin Rayner) is being visited by a young Oxford professor, C.S. Lewis (Mark H. Dold) who had satirized him in a book. His interest piqued, Freud invited him for a chat.

Mark St. Germain’s play was inspired by The Question of God by Armand M Nicholi Jr, who wondered, Did Freud and Lewis ever meet? A young Oxford professor had visited Freud after he immigrated to England, but his name is not known.

Freud was 83 and Lewis 41. Lewis, at the beginnings of his career as an accomplished novelist, medievalist, literary critic and professor at Oxford, had rejected Christianity, then returned to it, and as is common in such cases, became a fervent advocate, even a lay theologian.

Freud, of course, in his cynical, erudite way, had contempt for religion. They discourse, they argue, they jibe. Actually, Freud jibes; Lewis is more earnest. Freud asks, Why should I take Christ’s claim to be God more seriously than patients who claim to be Christ. And he tells Lewis that the desire to see God is a search for an ideal father figure.

Lewis insists that there is a God and those who believe are not suffering from a pathetic obsessional neurosis. What’s more, he sees in God the origins of morality, of the sense of good and evil.

Freud counters, What you call conscience are behaviors taught by parents. He rejects the Bible’s moralistic platitudes. The radio has reported Chamberlain’s demand that Nazi troops withdraw from Poland. When the sirens wail, Lewis helps Freud with his gas mask. Freud asks, Should Poland turn the other cheek to Hitler?

They argue about sex, with Freud declaring, The bible is a bestiary of sexuality! And about death. And the right to suicide, which Freud, suffering from inoperable cancer of the mouth, contemplates.

You feel as if you are present in a fascinating salon. The conversation between the two is stimulating, spellbinding. Rayner as Freud and Dold as Lewis are excellent in their roles. Rayner is powerful as the skeptical Freud, masterfully channeling Freud’s mind, spirit and body in his portrayal. Dold recreates Lewis as a committed but respectful interlocutor. They set intellectual sparks ricocheting.

Director Tyler Marchant expertly moves the characters around the set, Freud’s large wood desk and the inevitable couch – which in a turn-about Freud repairs to — even statues of gods and goddesses (Freud sees no conflict there), to draw you in, make you feel you are really in the master’s office, a copy of his Vienna study.

I thought that Freud easily won the debate. But maybe that depends on what view you arrived with.

Freud’s Last Session. Written by Mark St. Germain; directed by Tyler Marchant. Marjorie S. Deane Little Theatre, 5 West 63rd Street, New York City. 212-352-3101. Opened July 22, 2010. Oct 7, 2011 moves to New World Stages, 340 West 50th Street, 212-239-6200.