By Lucy Komisar

It‘s uncanny how Shakespeare could describe coup politics in modern-day Africa. Of course, what director Gregory Doran shows in this brilliant Royal Shakespeare Company production is that ambition, demagoguery, the manipulation of masses and betrayal of ones comrades haven‘t changed much since the era of Julius Caesar 2000 years ago or the treachery of kings and rivals closer to the Bard‘s time. Doran ingeniously sets the play in the continent now most prone to violent political upheavals.

On the Brooklyn Academy of Music stage, people in African dress moving to tribal music and marching with posters of Caesar greet the military victor. The white-suited Caesar (Jeffrey Kissoon) takes on a modern feel. He is smarmy and blustery as Mark Antony (Ray Fearon) offers him a crown. That the soothsayer warning about the Ides of March is a painted shaman hardly surprises.

The set is an expanse of broad white concrete steps leading up to a platform on which sits a huge golden statue of a man, whom we see only from the back. Though the population is clad in brightly colored pants, skirts and shirts, the actors in the political drama are set apart by dress of dramatic black and white.

There is a sense of déj vu as the conspirators, plunging long knives into Caesar, cry out “liberty” and “freedom.” Where have we seen this before? Where will we see it again?

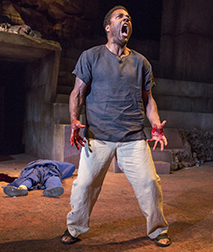

When Caesar‘s acolyte Mark Antony views the bloody corpse, he wails “Cry havoc.” Fearon, in white pants and a gray t-shirt, is a searing Antony. There will be bloodshed. Brutus (Paterson Joseph) tells the throng at Caesar‘s funeral that he went against the military chief because of his ambition, that they would have become slaves. Joseph exudes power and self-confidence as Brutus.

After the mob turns against the conspirators, Cinna (Chinna Wodu) is captured, a tire is thrown around his neck and he is dragged away. A favorite method that black South Africans used to kill accused traitors in the fight against apartheid was to necklace them – put tires around their necks and set the rubber aflame.

Then there‘s the always prevalent corruption. Brutus accuses Cassius (richly portrayed by Cyril Nri) of having an itching palm, of taking bribes for offices.

Some dialogue is not understandable because of the African accents, but as we know the play, that doesn‘t matter. In fact, the accent reminds us of another irony, that during the 1970s of the decades of imprisonment of members of the African National Congress on Robbin Island, a volume of Shakespeare‘s collected works was passed around among the prisoners, including Nelson Mandela, and annotated. Mandela put his initials on the lines of “Julius Caesar” that “Cowards die many times before their deaths. The valiant never taste of death but once. (What would Margaret Thatcher, the justly reviled British conservative prime minister who cruelly and crudely supported the apartheid regime, have made of the importance of Shakespeare to the imprisoned ANC leaders!)

At the end, the black cloaks are traded for camouflage and army boots worn by Brutus and his collaborators and the red berets and assault weapons of Antony‘s officers. In another eerie touch, the statue falls, like the one of Saddam Hussein pulled down by U.S. Marines. Will the next version of the play be set in the Middle East?

“Julius Caesar.” Written by William Shakespeare; directed by Gregory Doran. Royal Shakespeare Company at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton Street, Brooklyn. 718-636-4100 ext 1. Opened April 10, 2013; closes April 28, 2013. 4/21/13.