By Lucy Komisar

Susan Sontag was a precocious, smart, self-involved writer whose literary canvas was herself. Let me add the word “pretentious,” which seems best expressed by the white streak in her dark hair which in this dramatic memoir directed by Marianne Weems is exaggerated to a thick snowy patch.

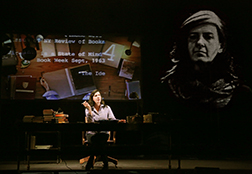

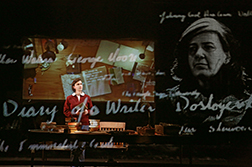

The play, based on her diaries and edited by her son David Rieff, is essentially the young Sontag (Moe Angelos) conversing with the older one (also Angelos) projected on a large screen. (The various projections by Austin Switser are brilliantly done.) The play is fascinating as a psychological if not a literary portrait.

The story begins with Sontag‘s youth, which sets the trajectory in this turgid commentary: “..What is it to be young in years and suddenly wakened to the anguish, the urgency of life? It is to… stumble out of the jungle and fall into an abyss…” She writes that childhood was a terrible waste of time.

Despite the childish prose, Sontag was smart and got into Berkeley at 16. We hear the list of all the books she has to read. (The book lists are repeated. We must understand that she read a lot.) We learn of her meeting in California with Thomas Mann: she kept a cigarette he gave her.

But the play surprisingly deals hardly at all with her own writing, other than to cite some titles and pub dates.

It‘s mostly about her lesbian sex life, which flowered when she left her University of Chicago professor husband and their child, David, and went to Paris.

Sontag described herself as bisexual, but that wasn‘t true. Prof. Rieff was her last man. We see her in Paris at a lesbian bar where women are dressed in men‘s clothes. She decides, “I want to sleep with many people.”

In Paris, she frequented the circles of celebrity women, including the daughter of Colette, a playgirl living off her mother‘s money. (This is not in the play.) Her big affair there, described in the script, was with the Cuban-American playwright Mara Irene Fornés. Her longest relationship, till her death, was with the American photographer Annie Liebowitz. That is also not in the play, which ends at an earlier time.

Sontag grew fond of her son when he got older and he wasn‘t in her professional way. One has to wonder at his conflicting motives in editing and presenting these texts by the mother who abandoned him. Because you don‘t get a sense of the brilliant writer, just of the sexual athelete. Why should we care about who she slept with in Paris?

My own view of Sontag‘s personality is colored by my experience as a board member of PEN, the writers group, during a few years in the late 1980s when Sontag was president. She presided at board meetings and when members spoke on issues, she intervened after every comment to say what she thought of that board member‘s view. It was the most inappropriate and outrageous behavior of a presiding officer I ever encountered in twenty years as a PEN board member. But when I saw this production of the self-centered, self-involved Sontag, I nodded in complete recognition.

Is this worthwhile as a play? Only if you have an insider’s interest in Sontag and her milieu. Otherwise, it’s a literary curiosity, although well presented by Weems and Switser.

Sontag died in 2004.

“Sontag Reborn.” Based on the diaries of Susan Sontag edited by her son David Rieff. Adapted and performed by Moe Angelos. Directed by Marianne Weems. Produced in collaboration with The Builders Association at the New York Theatre Workshop, 79 East Fourth Street, New York City. 212-460-5475. Opened June 6, 2013, closes June 30, 2013. 6/28/13.

Sontag reigns as one of my great heroes acquired in real time circa 1968 when I read, Against Interpretation. From that point, I was hooked on her mind. Thanks ever so sincerely for this fascinating review of this tacky play. You have saved me a good deal of time better spent meditating on the sign of Saturn and the erotics of art.