By Lucy Komisar

Robert Schenkkan has written a drama that should be performed in every city, every school and college in America. This play is both a stunning history lesson and a thrilling reenactment of one of the most exciting and important moments of recent American history. It‘s the struggle to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 at the moment when the civil rights struggle was roiling the south and capturing international headlines.

The flawed hero of the drama is President Lyndon Baines Johnson whose re-election slogan was “All the Way with LBJ.” The time was 50 years ago, and a lot of people who see the play and read this review may have only a vague memory of that time. It was vivid to me. I had just returned from a year in Jackson, Mississippi where, as a northern civil rights supporter, I edited the “Mississippi Free Press.” I knew many of the black and white activists portrayed in this play.

Johnson was flawed, of course, because he ratcheted up American presence in the war in Vietnam that John F. Kennedy had started. But he was also a giant.

The set is chairs and wood desks placed on risers that represent the Congress Johnson would deal with. And he does so splendidly. Schenkkan shows us Johnson as the most masterful politician who has occupied the White House since Franklin Roosevelt, and it‘s no accident that Johnson calls himself a New Dealer at heart.

You see Johnson sworn in as president after John F. Kennedy‘s death. It‘s the early 60s, the time of the civil rights movement, of Martin Luther King and southern student activists.

Johnson uses every sinew of his mind and body to enact the historic Civil Rights Act that would ban discrimination in jobs, education and public facilities. (The voting bill would come a year later.)

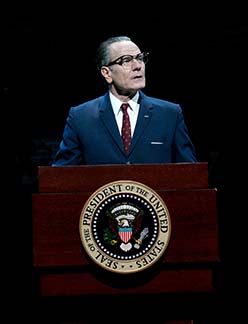

Bryan Cranston is brilliant as he channels LBJ‘s accent, his aggression, his sense of power. He wheedles and needles, schmoozes and sucks up to Southern Democrats and Republicans in the Senate and House whose votes have to be changed. What does a particular member want? Does he need black vote to win? Director Bill Rauch transports us in temperament and time.

John McMartin is excellent as Georgia Sen. Richard Russell, a key man Johnson had to turn around. He gets the Johnson treatment, with the president sticking his beaky nose practically in Russell‘s face as if trying to impale him.

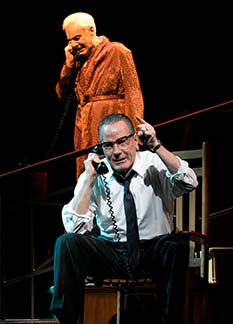

We see him playing to the vanity of Republican Sen. Everett Dirksen (Richard Poe) who he knows wants to be a great man. Or on the phone: “Senator Hayden! For sixteen years, the thirsty citizens of Phoenix and Tucson have been waiting with the patience of Job for your Central Arizona Water Project. California‘s got the water and your people need it. You vote for cloture and I will personally see that water flowing and your deserts bloom.”

We see the scurrilous FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover who wiretaps Martin Luther King‘s advisor Stanley Levison, a New York leftist who Hoover, a villain of the piece, uses to smear King because Levison years ago had been an (ideological) communist, ie guilty of a thought crime. (In spite of the First Amendment, expressing certain ideas was not allowed.)

The Washington Post publishes Hoover‘s attacks with gusto. (Time Magazine also ran stories about King’s communist connections.) When agents learn of a plot against King‘s life, Hoover says, “Inform the local authorities.” He‘s told, “They may be involved.” He repeats, “Inform local authorities.”

Hoover also isn’t above blackmailing LBJ as he had presidents before him. (That raises the question about the power of whoever has access to NSA data, that proliferates surveillance, to blackmail presidents.)

Hoover also targets Walter Jenkins, Johnson‘s long time aide, who is caught inappropriately in a men‘s room. Of course, everyone now knows that Hoover, who lived with his “40-year companion,” Clyde Anderson Tolson, was gay. Hypocrisy writ large. When will we change the name of the FBI building so it doesn‘t honor this abominable guy?

One of the best back stories is of Sen. Howard Smith (Richard Poe), Virginia Democrat and racist, who adds a ban on sex discrimination to the Civil Rights bill “to protect white Anglo-Saxon women.” The purpose of course is to derail the bill. He knows his colleagues! When the bill passes with the amendment, he and his racist-sexist fellows get hoist on their own petard! Feminists would laugh heartily about that.

Johnson beats back an attempt to exclude schools and jobs from coverage by the bill, which is finally voted by the Senate June 19, 1964. (Please read that sentence again. It would have been okay to refuse to hire blacks or let them into schools.)

Schenkkan does more than tell, “this happened, that happened.” He explains the roots of the opposition. It wasn’t just about nasty racist southerners, it was (and still is) about economics.

Johnson says, “This ain‘t about the Constitution. This is about those who got more, wantin‘ to hang on to what they got, at the expense of those who got nothin‘. And feel good about it. Uncle Dick can talk about his Rights ˜till he‘s blue in the face, but all I see are the faces of those little kids in Cotulla.” That’s the rural Texas school where he taught 1928 to 29.

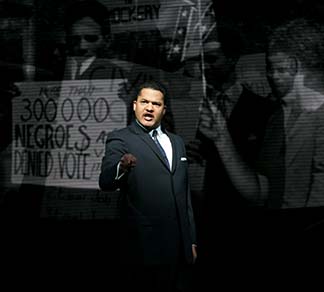

Many of the actors look and sound like their characters. Robert Petkoff is excellent as the sincerely liberal Sen. Humphrey, who desperately wanted Johnson’s support to be president and traded his principles for it. To no avail. Bob Campbell is a mirror image of Alabama Gov. George Wallace. Brandon J. Dirden excellently conjures up Martin Luther King, Jr. and Peter Jay Fernandez channels NAACP leader Roy Wilkins.

The actors do less well – or maybe they don‘t try – to emulate lesser known characters such as Bob Moses, who organized SNCC workers in Mississippi and the voter registration Freedom Summer of 1964. Moses is a soft-spoken but charismatic man. You get nothing of his character from Eric Lenox Abrams‘s portrayal. You also miss the sense of the irony and humor in William Jackson Harper‘s Stokely Carmichael, who I also knew, and who sprinkled his conversation (at least in his Howard college days, the period of the play) with Yiddishisms that he picked up at the Bronx High School of Science.

We get the players on both sides, the liberals – Sen. Hubert Humphrey (D-MN), Rep. Emmanuel Cellar, (D-NY) and the racist southerners — Richard Russell (D-GA, Robert Byrd (D-WV), William Eastland (D-MI) and Strom Thurmond (D-SC). The bigoted southern senators are cruder than their progeny are now, using terms such as mongrel to describe black people. (Or maybe that still exists on Fox News.)

A turning point is the June 21, 1964 murder of three students by klansmen in Neshoba, Mississippi. It is just months before the Democratic Party convention in Atlantic City.

We see Roy Wilkins‘s opposition to the SNCC-supported Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party‘s challenge to the all-white state delegation. Wilkins is an establishment civil rights leader who fears antagonizing liberal Democrats. But King says, “We have to take a stand.” Wilkins laid the groundwork, but it is the radicals that bring change.

Also important in the history that this play establishes are less well-known Mississippi civil rights leaders Ed King, a white minister, and David Dennis a black CORE official, who are significant actors in Jackson. It shows the depth of Schenkkan’s research that they are in this play.

Then at the beginning of August 1964 comes the Gulf of Tonkin event, which is misreported by the White House as an attack by North Vietnamese on a U.S. patrol boat. There is actually no attack. (Does this remind you of the non-existent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq invented by George W. Bush to foam the runway for his invasion? Plus Òa change.) But on August 7, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution passes, 416 to 0 by the House and 88 to 2 by the Senate, saying the President could take all necessary measures to repel armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression. So, no declaration of war by the Congress is required. The two Senators who deserve admiration for opposing jingoist war posturing are Wayne Morse (D-OR) and Ernest Gruening (D-AK).

The play suggests the move is a ruse to get tough on the Republican challenger, Barry Goldwater. But Johnson sinks his own legacy.

The Democratic convention becomes a rout. Humphrey tries to win a compromise by giving two non-voting seats to the Mississippi Freedom Democrats. The state party would not be permitted to send segregated delegations in the future. Johnson – nasty, aggressive, yelling — is personally offended by the actions of people who he thought he did so much for. He goes on TV to cut into the broadcast by MFDP leader Fannie Lou Hamer. He orders Hoover to spy on Hamer, Moses, and King.

But LBJ is also horse-trading on the other side, as the white Mississippians threaten to support Goldwater. He tells Eastland, “You know, Jim, I get grief all the time from Northern liberals, “How come we gotta pay Mississippi farmers NOT to plant?” Mebbe they‘re right. Since I‘m not gonna carry Mississippi anyway, maybe I oughta cut your goddamn six million dollar cotton subsidies! How much of that do you receive on your plantation down there in Sunflower County?”

Johnson achieved the major civil rights legislation of our time. And he did it by manipulating and threatening members of Congress who were racists. Could it have been done any other way? Not as long as masses of blacks had no right to vote. It‘s a fascinating story of progressive change in an imperfect democracy.

The other mystery is who is the real Johnson. He seemed set against Humphrey, the good liberal. On the other hand, to believe Johnson‘s memory of his young days teaching school children in the poor Hill Country, he had a liberal commitment. If only his machismo hadn‘t gotten sandbagged by the Vietnam War, by men such as Robert McNamara and by American militarism – another story. And let‘s add that while Jimmy Carter added human rights to the international lexicon, nothing was done to advance human rights by Kennedy, Clinton or Obama. (Forget the Bushes.) The irony is that, apart from Vietnam, Johnson was the most important progressive American leader since Roosevelt. No one else has come close.

“All the Way.” Written by Robert Schenkkan; directed by Bill Rauch. Neil Simon Theatre, 250 West 52nd Street, New York City. 866-448-7849 (automated) or 800-745-3000. Opened March 6, 2014; closes June 29, 2014. 5/7/14. Review on NY Theatre Wire.

Right on! You’ve really told it as it is. A must-see play that tells today’s younger people what happened and how it happened. The play gives us the opportunity to see the horse trading needed to get critical legislation passed by Congress. Oh that the current Congress could do what needs to be done to renew the voting rights and social legislation and overcome the right wing Supreme Court.