By Lucy Komisar

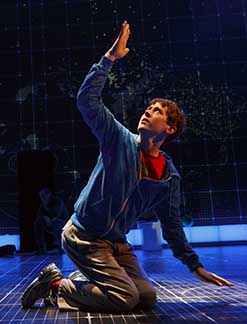

The star of this mesmerizing production is director Marianne Elliott. Her co-star is video designer Finn Ross. Of course, Alex Sharp is superb as the intense, erratic, edgy, wound-up Christopher, the 15-year-old autistic youth whose mind works like a machine but who can’t get personal connections in gear. He is literal, as precise as math. “Where is heaven?” he asks the pastor. He speaks in great detail but doesn‘t like metaphors, because they obscure reality. When a cop says, “Park yourself,” he goes “beep! beep!” and moves backwards.

The play by Simon Stephens is adapted from Mark Haddon‘s novel, which is told in the first person. Here is a case where the play may be better than the book. The visualization of how Christopher thinks and perceives the world is stunning and one of the best uses of video in a theatrical production I have seen.

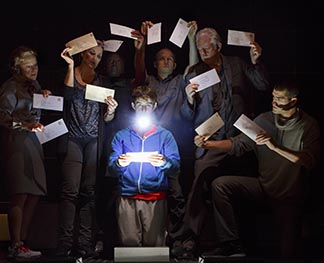

The set is a box made of sides of graph paper, white lines on black. Sometimes, objects are taken out of a square of wall that suddenly becomes a shelf or drawer. Christopher thinks like that mathematical graph. The people of the story all sit on ledges around the set, as they exist in his mind.

The story, which is rather thin, revolves around the mystery of who killed Wellington, the neighbor‘s big white dog. The murder weapon, a large garden fork, is still stuck in the animal when we see it. Christopher is accused of the crime, denies it, and resolves to find the culprit. In the course of his detective work, he writes down everything he learns or that happens.

The play title is from a line in the Sherlock Holmes story, “Silver Blaze,” about a dog that doesn‘t bark, because it knows the killer. And Christopher of course is as methodical as Holmes.

So much is in his mind, and Francesca Faridany as Siobhan, his special-education teacher, recites from his chronicle, which tells us what goes through it.

His father, Ed (Ian Barford) had informed him his mother had a heart attack and died in hospital. (Barford is good as the broad-shouldered working-class guy.)

His investigation turns up the fact that his mother was having an affair with a neighbor. He writes that down. In fact, Judy (Enid Graham, fine as the distraught mother) could not handle Christopher’s behavior — he even screamed when she held him — decamped from Swindon to London with her lover (Ben Horner), the ex-husband of the lady who owned the dog.

The plot takes another turn when Ed comes across the journal. And hides it. But ever the detective, Christopher methodically searches and finds it. And a cache of letters. In the visualization, letters fall out of the sky and he collapses. (Here‘s a metaphor made real!)

It turns out his mother had written repeatedly to Christopher from London.

He resolves to go to London to find her. Here‘s where the set (by Bunny Christie) and lighting (by Paule Constable) become spellbinding. Planning the trip, he uses little houses to represent the village where he is and the place where his mother is. They are connected with a train track complete with model train.

In London, the Tube is a projection of diagrams and staircases – one of which he slides down. He is never intuitive, only arithmetically exact – using a map book, he walks at right angles to find a destination. Red lights dance on the wall map as he walks through streets.

As in any Holmes mystery, the boy‘s pulling together the strands of everyone‘s motives will solve the killing. But by then, we don‘t care about Wellington, we care about the amazing young man whose psychological handicap is overshadowed by a special kind of genius. It’s a riveting production.

“The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.” Written by Simon Stephens, adapted from Mark Haddon‘s novel, directed by Marianne Elliott. The National Theatre at the Barrymore Theatre, 243 West 47th Street, New York City. 212-239-6200. Opened October 5, 2014. 10/21/14.

Perfect review of a thrilling play.