By Lucy Komisar

Whatever playwright Susan-Lori Parks turns her hand to is bound to be surprising and memorable. Her latest work, the first of three parts, is a brave Brechtian drama about slaves during the time of the Civil War. Nothing and no one are quite what they seem. It‘s a commentary about blacks today who sell out their people for, what? (Can we put Clarence Thomas in this equation?) And a powerful feminist commentary.

The characters boldly represent archetypes. There is the villain slave master (Ken Marks), Homer (Jeremie Harris) the brave young slave who attempts to escape, Hero (Sterling K. Brown), the misnamed slave who turns him in, Penny (Jenny Jules), who loves Hero, and a captured Union soldier (Louis Cancelmi) who turns out to be only passing for white and challenges both master and Hero about their attitudes about slavery. The acting is cool and superb. Director Jo Bonney makes surreal events seem natural.

The mood is drab, the costumes are drab with raggedy gray and tan clothes. But the country music performed by Steven Bargonetti sets a strong mood.

Parks challenges a lot of stereotypes about how black playwrights might deal with slavery, starting with the fact that Hero is an anti-hero.

As it‘s just the first part of projected series that continues the story, we can‘t know yet the sense of it all, yet one wonders at what will happen in the next odyssey of a man, now called Ulysses, who starts out betraying fellow slaves.

In the first play (really an act, but called a play), slaves are chatting, wondering whether Hero will go to the war with his confederate master, who has promised him freedom for his service. He opines, “I was thinking I‘d be on wrong side.” By the way, he‘d been promised his freedom before and the master reneged. So why do these slaves (writ the current oppressed) keep believing their oppressors?

Yes he does go to war with the master, a Confederate colonel. Second chance for freedom. First was when he caught Homer, who had run away, and at the master‘s order he cut off his foot. He explains to Penny, “I got a chance at getting something.” Freedom. Is that how a hero gets freedom?

And to emphasize the humiliation, he has to run behind the boss master who rides on a horse. It requires him to foot through horse droppings. And flying bullets.

In the second play, he is in a clearing with the colonel and Smith, a captured Union captain who is held in a bamboo prisoner box. (It reminds one of the Vietnam tiger cages the American side used.) He asks the captain if he ever wanted to own a slave. The response is “No.”

It turns out that the “captain,” who claims he commands a troop of colored soldiers from Kansas, is actually one of them – he just appropriated the jacket of an officer. When the master leaves, will Hero free the “captain?”

There is no subtly about where power resides. The colonel declares, “I am grateful every day that God made me white. As a white I stand on the summit and all the other colors reside beneath me, down below. For me, no matter how much money I‘ve got or don‘t got, if my farm is failing or my horse is dead, if my woman is sour or my child has passed on, I can at least rest in the grace that God made me white.” (Please translate that to how poor Southern whites are encouraged to feel.)

Hero is not so sure he wants the freedom that the war could give him.

HERO How much you think we‘re gonna be worth when Freedom comes? What kind of price we gonna fetch then?

SMITH We won‘t have a price. Just like they don‘t. That‘ll be the beauty of it.

HERO Where‘s the beauty in not being worth nothing?

SMITH We wont be able to be moved around, beaten, bought or sold, forced to work and make men rich while we stay poor.

HERO Most soldiers they‘re poor, colored and white both.

SMITH There‘s more to Freedom than I can explain, but believe me it‘s like living in Glory.

HERO Who will I belong to?

SMITH You‘ll belong to yourself.

HERO So—when a Patroller comes up to me, when I‘m walking down the road to work or to what-have-you and a Patroller comes up to me and says “whose Nigger are you, Nigger?” I‘m gonna say “I belong to myself?” Today I can say “I belong to the Colonel.” “I belong to the Colonel,” I says now. That‘s how come they don‘t beat me. But when Freedom comes and they stop me and ask and I say “I‘m my own. I‘m on my own and I own my ownself,” you think they‘ll leave me be?

SMITH I don‘t know.

HERO Seems like the worth of a colored man, once he‘s made Free, is less than his worth when he‘s a slave.

Subtle powerful point. When the people in power set the price, blacks were worth more than they could command free.

In the last act, some slaves are planning to flee and are spending the day outside the unpainted, weathered cabin Penny now shares with Homer. Penny has never stopped loving Hero, who arrives with the news of several betrayals. He is both the victim and the perpetrator.

At first Penny agrees to fix up the cottage for Hero and the new woman he has brought back. She says, “Why I thought I deserved something special, I‘ll never know. I‘ll go inside and make the house ready. For you and for your new bride. You can count on me, Old Hero, to do at least that.” She dutifully goes into the house.

And then there is a feminist challenge.

The runaway slaves declare / sing:

The place I‘m going now is Freedom

But where is Freedom, really?

Will the air smell sweet?

Will the streets be paved with gold?

Will all in Freedomville welcome me with open arms?

Will there be food?

Will there be a bed to lay my Freedom-head?

Freedom will swell me, maybe

Maybe it will burst my brains to madness

Maybe it will flood my heart to death

Will I say, at the end of the day,

“God, I wish I‘d stayed home?”

I‘m afraid of what will happen next.

Inside, Penny makes up the marriage bed

And in doing so she takes her place in a long line of the Wronged.

Come out of the house, true wife, true love,

Come with us

Come with us

Come break the chain.

Come break the chain.

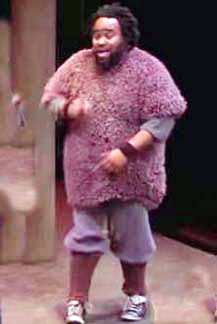

Finally, Hero has only the critical loyalty of Odyssey Dog, the terrific comic Jacob Ming-Trent dressed in a shaggy rug, to tell his shaggy dog tale. Is Odyssey Dog the voice of Parks?

Father Comes Home From the Wars. Parts 1, 2 & 3. Written by Susan-Lori Parks; directed by Jo Bonney. American Repertory Theater at the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, New York City. 212-967-7555. Opened Oct 28, 2014; closes Dec 7, 2014. 11/14/14.

who is the father of Penny’s baby – Homer or Hero?

LK: I would say Hero, since Penny loved and still loves him.