By Lucy Komisar

Love, sex, age and class. Key elements in David Hare‘s 1995 play about a rich guy who had an affair with an employee a few years before and would like to start it up again.

He runs restaurants. She was a lawyer‘s daughter (ie. privileged) who wandered into his eatery on London’s Kings Road and got a job. And a promotion. And a lover. She left six years later when his wife discovered the affair.

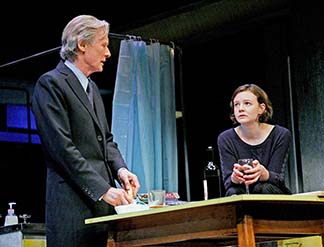

First issue is that with Hare, a writer of the left, the story should be about political attitudes. The script calls for Kyra to be just past 30 and Tom to be near 50. Carey Mulligan who plays Kyra is 29. But Bill Nighy is a craggy-faced 65. Nighy is a terrific actor, but this is bad casting. The script’s age difference is large enough, but in this case she could be his daughter.

Stephen Daldry’s direction is at once smooth, sharp and subtle, but he is directing another play, which has to do with a poor young women and a rich old man. It confuses the issue.

We are in Kyra‘s apartment in a working class part of northwest London. The kitchen has a plain wood table, two chairs and a water heater. Through translucent back walls we see the fa§ade of another council flats building across the courtyard.

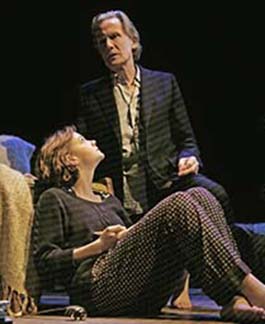

She doesn‘t have money. She teaches poor kids – not what the society values. She wears pants and a baggy sweater. Her flat is cold. Mulligan is cool, realistic.

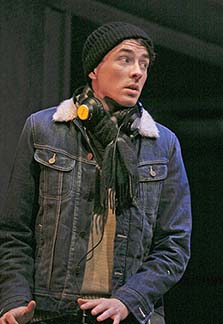

Tom‘s son Edward (Matthew Beard) arrives unannounced. Beard is terrific as an edgy jittery 18 year old. He‘s dealing with the death of his mother and an unresponsive father.

Later Tom appears, with a bottle of whiskey. He has longish gray hair. He is rich and self-involved. He has already “discounted” his wife‘s death. Discounted: a business term. He pointedly won‘t take off his coat, because it‘s too cold. He is insufferable.

It‘s three years after the affair. He accuses Kyra of having a bad attitude to business. In some ways, this is a funny satire.

He says, “Then – oh Christ! – there‘s this fatal moment. Expansion!”

Kyra: “Sure.”

Tom: “And then you borrow. And then you‘re no longer in business, you‘re no longer in what I‘d call business, because it‘s nothing to do with the customer. It‘s you and the bank. And it‘s war! They always have new ways of punishing initiative.”

Nighy‘s facial expressions are as good as dialogue, reporting his fury and anguish. (Sometimes it seems like overacting.) During all of this, Kyra is (really) cooking Bolognese sauce for pasta. Steam comes from the pot.

About the morality of businessmen, we discover that Tom left his wife as she lay dying. Wouldn‘t Kyra like to join him in his house on a Caribbean island?

This play is about values; theirs are now different. She has left the warm bubble of money. Challenged by dealing with poor kids from other countries, she talks about seeing England as it really is. She says “Most people live differently. You have no right to look down.”

He snobbishly disdains her for teaching people at “the bottom of the heap.” He says, “You could be teaching at any university.” He accuses her of female stubbornness.

She responds furiously: “I‘m tired of these sophistries. I‘m tired of these right-wing fuckers. They wouldn‘t lift a finger themselves. They work contentedly in offices and banks. Yet now they sit pontificating in parliament, in papers, impugning our motives, questioning our judgements. And why? Because they themselves need to feel better by putting down everyone whose work is so much harder than theirs.”

She tells him, “Anyone can play. But there‘s only one rule. You can‘t play for nothing. You have to buy some chips to sit at the table. And if you won‘t pay with your own time … with your own effort … then I‘m sorry. Fuck off!‘”

He accuses her of not giving herself in love. That she loves the people, because she doesn‘t have to go home with them.

Why do men always think it‘s all about them?

Kyra: “I mean, apart from anything, there is the arrogance, the unbelievable arrogance of this middle-aged man to imagine that other people‘s behavior – his ex‘s behavior – is always in some direct reaction to him.”

So, the guys who were turned on by an older man-young women meme will get another lesson. And David Hare fans will get another example of why his plays always deliver a deft political message.

Skylight” Written by David Hare; directed by Stephen Daldry. John Golden Theatre, 252 W. 45th Street, between Broadway and 8th Avenue, New York City. 212-239-6200. Opened April 2, 2015; closes June 21, 2015. 6/5/15.

Why is it that in situations promising good focused sex (and one has to assume good sex, absent off-putting peripheral problems, such as age, class, politics etc.) it isn’t recognized that the transaction is complete in itself? It’s a closed circuit. Anything else is unalloyed Puritanism raising its usual ugly head.

The human condition is complicated enough without these intrusions into Mother Nature’s need to be satisfied, which is proved by her providing the means to achieve pure pleasure. Without it, none of us would be here. Enough to say aren’t they lucky in this play, be cool, keep it that way, and good luck to them.