By Lucy Komisar

This is a moving paen to the bomb-throwing and window-smashing militant British suffragists. A powerful play written and directed by John Woudberg and vividly performed by Claire Moore, it will set every feminist‘s blood boiling in anger and pride at what Edith Rigby, a heroic woman who forswore the advantages of being a doctor‘s wife, suffered and achieved in the British struggle for the vote. Suffered means being beaten and force-fed in jail hunger strikes, which today one recognizes as torture.

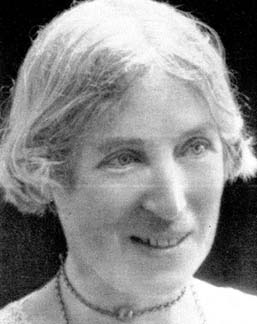

Rigby’s appearance is bourgeois, as Moore wears an upsweep, green velvet jacket and long purple skirt. Her father was also a doctor, though with ten children life wasn‘t always easy, and she was sympathetic to the poor. Early on she was a breaker of rules. Her story starts when at 16 she is the first woman in Preston, Lancashire, to ride a bicycle. A scandal. Does this remind you of Saudi Arabia banning women drivers?

Moore performs this piece as she might recite a dramatic poem. She tells how Rigby marries Charles, 13 years older. He understands that life with her won‘t be “a walk in the park.” When Charles demands she do his bidding, because he pays the bills, she shrewdly leaves the household and finds a job as housemaid, so she can pay her way. He drops the demand.

She is concerned about young women working in the mills and asks about their pay, hours and working conditions. She starts a school for working girls. Rigby explains, Injustice weaves its thread through these girls lives, these women in waiting whose potential chokes and dies. Girls, sharp as tacks, who never will be teachers. Born-leader-girls who never will lead – girls of social-conscience, who can’t become MP’s. Moore makes Rigby come alive and also plays many parts, taking the voices of neighbors and others in the drama.

In the early 1900s, Rigby joins the women‘s movement led by Emmeline Pankhurst. When at a demonstration she is knocked down and beaten, Moore tells us that she is “forged in flames” and must go to jail or die. She organizes in town and brings people to a march of 3,000 through Hyde Park to parliament. Men heckle, “Darling do you wish you was a man?” She replies, “No, do you?”

Women, led by the fearless Pankhurst, sing “Rise up women” to the music of “Glory, glory hallelujah.” Mounted police knock them down, beat them, jail them. When they leave prison, hundreds welcome them.

In the play, Moore recites her elegant lines, What makes a little girl of principal, become a lurking shadow in the night? A breaker of rules? Of windows? A breaker of heads?…..Knowledge!

The movement grows to 300,000 activists. They challenge Prime Minister Asquith at dinner parties, they smashed windows, chain themselves to the PM‘s residence at Downing street. They declare they are political prisoners and fast. King Edward recommends they be force fed, which is now defined as torture. It‘s done through the mouth, nose, anus, vagina. So, this torture is also rape. Police grab their privates, twist their breasts. The women suffer broken heads and limbs. Two die from injuries. The upper-class notion of chivalry towards women is a gruesome joke.

Still, they persist. In 1912, they set letter boxes ablaze. Rigby throws black pudding at a Labor MP, is arrested, goes on hunger strike. The women set off a bomb at a railroad station and fight their police assaulters with clubs.

Rigby says, If Boudicca and Joan of Arc, Queen Elizabeth and Nightingale can’t prove women’s worthiness to vote then women must be seen to break the law! (Boudicca was queen of the British Celtic Iceni tribe who led an uprising against the occupying forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60.)

Are they condemned for their violence? She responds, “Men‘s causes have drenched the world in blood.” (Men’s goals had been to obtain resources and markets, not anybody’s freedom.)

At the start of World War I, the women suspend the fight for the war effort. And when it‘s over, a 1918 law gives the vote only to women over 30 with property. So, denying women the vote was not just about gender, it was about class. Perhaps working class women lacked upper class sympathies. It was another ten years before women could vote on the same terms as men.

Rigby retires to Wales where she dies in 1948 at 76. She was an extraordinary person, and this play should contribute to the public attention she deserves.

“Woman on Fire.” Written and directed by John Woudberg and performed by Claire Moore. TheSpace, Edinburgh Festival Fringe, August 2017. 8/14/17.