By Lucy Komisar

Aug 9, 2019

At the Whitney‘s summer exhibit, a rich retrospective of decades of art produced in America, are some highlights that show politically aware painters reflecting the important struggles of the era, against the oppression of workers, against fascism, against racism.

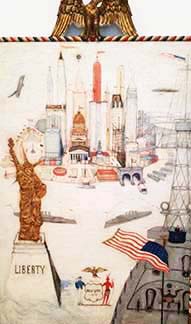

It opens rather na¯vely with Florine Stettheimer‘s “Liberty” (1918-19), the earliest work in the exhibit. It was done to celebrate the end of World War I, with the Statue of Liberty apparently swathed in gold camouflage, staking out a scene of soaring warplanes and skyscrapers glorifying victorious capitalism. Ten years later the stock market crash put a different spin on that.

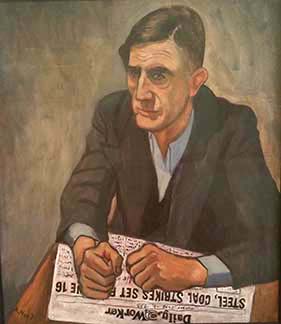

It was hardly “liberty” for all. Alice Neel, a committed leftist, in 1935, in the midst of the Depression, paints Pat Whalen, a longshoremen union organizer in Baltimore.

He holds a copy of “The Daily Worker,” the Communist Party paper. For Neel, he represents the fight for social justice, his fists at the ready.

Workers continued to struggle till the next war, World War II, when in the capitalist answer to unemployment, the state simply drafted them.

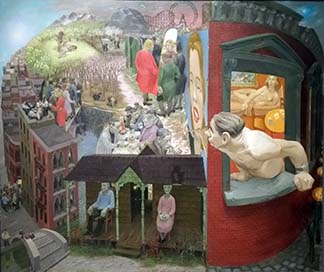

One of the draftees was Henry Koerner, a Jewish escapee from Nazi Austria. In the U.S. military, he was sent to Europe where he sketched the Nuremberg trials.

When he returned to Vienna in 1946, he learned his parents had died in concentration camps. “Mirror of Life” (1946) shows night and day, biblical events and the present, a chaotic reality. The man leaning out of the window is the artist. Hear Koerner’s son speak on the audio guide at #764

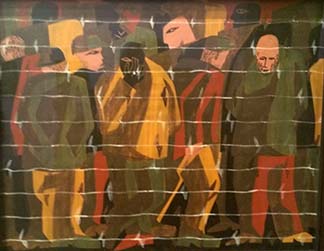

Jacob Lawrence spent his first year of service in the World War II fight against fascism in a racially-segregated U.S. military unit in St. Augustine, Florida.

But a commander, who appreciated art, helped him move to an integrated regiment as an artist, and he documented the war in Italy, England, Egypt and India. In 1946 he won a Guggenheim Fellowship to paint the War Series 1946-47.

Here are two of the 14 paintings: “Going Home” and “Reported Missing” (1947). Hear about the series on the audio guide at #770

Norman Lewis, an abstract expressionist, made “American Totem” in 1960 at the cusp of the 1960s civil rights movement.

The hooded Klansman is made of forms that appear to be apparitions, skulls and masks, the terror is abstract but also real.

“The Whitney Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965.” The Whitney Museum, 99 Gansevoort Street, NYC, between Washington and West Streets. (212) 570-3600. 10:30am to 6pm, Fri and Sat till 10pm. Pay what you wish Fri 7 to 10pm. Open daily July and Aug. Closed Tuesdays Sept-June. Mobile guide.

Photos by Lucy Komisar.