By Lucy Komisar

March 23, 2020

Knockout details about how Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky used transfer-pricing in sales of Yukos oil to cheat the Russian government and minority shareholders of massive amounts of money are found in this seemingly staid business-academic book by Mikhail Glazunov.

Glazunov, now an independent consultant, has been a Lecturer in the Department of Business Studies at the University of Hertfordshire, UK, and Chief Executive Officer of a Russian company.

Transfer pricing, he explains in business-academic speak, operates as an instrument for the distribution of costs and profits between different corporate units and does not represent real market prices.

It works this way. One part of a company sells to another part at a fake price “reducing the firm‘s effective tax rate and lowering the cost of capital.” Cost of capital is a way of saying investors are cheated of dividends.

He explains, “the profit is shifted to a region where tax avoidance is easier due to tax administration being fragile, with less strict enforcement of fiscal laws; or to a region with high corruption, where tax can be reduced to zero.”

The case of Yukos Oil Company

He writes: Yukos Oil Company was created on 15 April 1993 and included the oil extraction enterprise Yuganskneftegaz, three oil refineries in the Samara region, oil distribution networks in a few Russian regions and a number of construction and service companies. In 1995, the oil extraction company Samaraneftegaz and several research and industrial organisations were added to the assets of Yukos.

By the end of 1995, the Russian government decided to sell state-owned shares. The sale was carried out in several stages: 45 per cent of the shares, in the public domain, were put up for auction escrow; 33 per cent of the shares at an investment tender and 7.96 per cent at cash auctions. Another 7.04 per cent of the shares were distributed among the workforce of Yukos and 7 per cent of the balance transferred to the company for resale in the secondary market.

He describes Khodorkovsky‘s corruption.

“The winner of the auction and the investment competition was the firm Laguna, which was owned by the bank Menatep. Shares traded on cash auctions were mostly acquired by structures close to Menatep. In December 1996, Menatep bought the government stake in Yukos, which was in pledge, and became the owner of 85 per cent shares of the company.” By the way, the auction was run by Menatep!

He says Yukos over several years became one of Russia‘s largest oil companies. Then he inexplicably says it became “a leader in corporate governance reform.

Reform? He has described a corrupt auction. He will shortly tell of massive transfer-pricing tax evasion. Once MBK had stolen Yukos and other companies, he did some serious PR, and western media and academics drank his Kool-Aid about now he was going straight.

In 2000, Vladimir Putin became president of Russia after the death of Yeltsin. People like Khodorkovsky found they could not get away with what they had gotten away with before.

Glazunov notes that Khodorkovsky‘s October 2002 arrest was for “acting illegally in the privatization process of the former state-owned fertilizer company Apatit. In addition, he was charged with large-scale tax evasion.”

and important player in the oil industry, from Wikipedia.

Khodorkovsky has protested that he was being taxed more than company profits. But Glazunov points out that “the high value of claims was due to an unprecedented level of fines” due to the deliberate nonpayment of taxes.

How the tax cheating worked

Taxes had been “calculated as a percentage of the commercial oil sales revenue of oil companies.” According to the scheme developed, an oil extraction enterprise sold wellbore fluid subsidiary companies, which were registered in territories with preferential tax rates dramatically lower than in other parts of Russia. All the companies were created in December 1997 and controlled by the management of Yukos.

Wellbore fluid is a mixture of oil, water, salts and impurities such as sand. It is not a commercial product and its production is not liable for tax because the object of taxation under the tax code is dehydrated, desalted and stabilized oil. The wellbore fluid was delivered by the Sverdlovsk‘s company to the plant located near the well, where commercial oil was extracted.

Oil was sold to the companies registered in the Sverdlovsk region and in Mordovia at a low price, based on the fact that this oil and raw materials were not used for production. Then the wellbore fluid was delivered to the plant located near the well, where it was extracted for the preparation of commercial oil. The company paid taxes at the regional special rate and paid income in the form of dividends to its offshore shareholder.

Using the offshore system

Dividends were included, if needed, in the consolidated balance sheet of Yukos. For optimizing this tax, the factory capacity of refineries was rented to companies which bought oil and oil products at the lowest prices and sold at market prices on the domestic market or abroad. Export products were bought out by foreign offshore operations associated with Yukos, and then sold at world prices.

Glazunov writes, “Allegedly, these schemes enabled Yukos and its affiliates to reduce its revenue for the year 2000 by 210 billion roubles, and the government sued the company for $28 billion for back taxes and penalties. These schemes were legally justified, they were assured by the large international auditors and were admired by minority shareholders, for which Yukos was positioned as the most profitable and efficient oil company in Russia.”

Thievery pays!

Glazunov added, “It must be noted that similar schemes were used by all Russian oil companies, but only Yukos used the version with wellbore fluid.

Khodorkovsky found guilty

On May 16, 2005, the judgment of the Meshchansky District Court (Moscow) found Khodorkovsky guilty of the crimes stipulated under different Articles of the Criminal Code and imposed a final sentence in the form of imprisonment for a term of nine years in a correctional colony. As a result, the main oil-producing assets of Yukos became the property of the state oil company Rosneft, and the company Yukos became bankrupt.

He quotes another source as noting that vertical integration and transfer pricing were used by most mining companies.

He says that other companies received a higher tax bill due to the inferior talents of their lawyers and accountants in comparison with those of Yukos, who used tax optimization techniques and efforts to protect the legality of these activities on an extremely large scale. For a long time, the Yukos government relations department successfully blocked any resistance of regional authorities to tax optimization, including the arbitration courts, but this led Yukos management to a loss of vigilance and they were not forced to think about urgent changes in company strategy.

“Tax Optimization” is the international corporate way of saying how to evade taxes.

While the West bought Khodorkovsky‘s story that the government went after him on taxes, because he brought attention to government corruption, Glazunov says, “Yukos is not an exceptional case; the Russian government has initiated other similar investigations against large oil companies that employed transfer pricing and demanded back-taxes and penalties. The oil giant Lukoil got a $200 million back-tax claim for 2000 and 2001 for use of transfer pricing. The TNK oil company was hit with a tax claim for nearly $1 billion for 2000.

His citations about Lukoil and TNK are from this article I wrote for CorpWatch in 2005.

Citizens think backroom asset deals are frauds

He quotes Paul Klebnikov, the Forbes journalist murdered in Moscow in 2004, that when a business buys state assets in the course of a backroom deal and at such a low price, it takes the large risk that its rights to the new property will never be safe. Citizens will consider this business as a fraud, and the state will take it as a custodian rather than the asset‘s real owner.

Glazunov says that “transfer pricing was the dominant strategy in almost all large Russian oil companies in the 2000s.

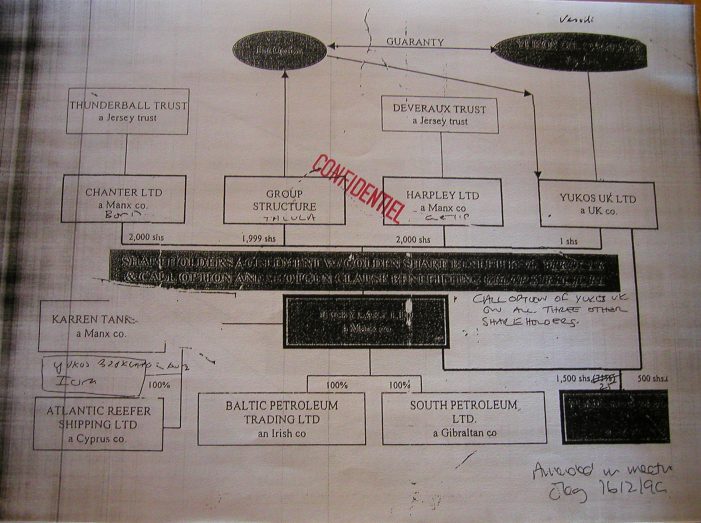

He writes, “In all cases, large oil companies‘ production subsidiaries sold crude oil at dramatically below-market prices to shell companies which were established in SEZs (special economic zones) and were affiliated with the central companies. Shell companies sold oil and/or petroleum products to domestic and foreign buyers at market prices, they also managed to resell oil or oil products a few times between different affiliated companies which could be in different jurisdictions and had different tax benefits.” Note the offshore chart above.

“Companies strictly controlled the full processes of the shell companies through placement of directors, force support and contracts with the shell company. Under contracts, oil giants organised the purchase, transport, processing and sale of oil and petroleum products. The shell companies received the main part of the profit resulting from the sale of oil. The transfer pricing policies allowed oil giants to avoid taxes as the shell companies had large tax privileges in different sorts of taxation.”

Western commentators and governments look back at the Yeltsin period with nostalgia. Since Western banks run the offshore system, they probably got a nice piece of the action.

Corporate Strategy in Post-Communist Russia, by Mikhail Glazunov, Routledge, 2016.

Pingback: Aussie Channel 10’s The Project a stenographer for fraudster Wm Browder aimed at pressuring Parliament & Foreign Minister to protect his looted $millions – The Komisar Scoop