By Lucy Komisar

April 18, 2021 – I met Bob Zellner in 1960 at the Shaw University, Raleigh NC, conference that founded SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the youth shock troops of the 1960s civil rights movement.

He was a young white guy from Alabama who had signed on to the movement at a time that most whites north and south were uninterested, noncommittal or on the other side. I was also a white activist.

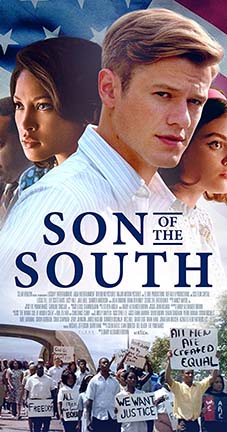

This compelling docudrama, “Son of the South,” by Barry Alexander Brown, is based on Zellner’s 2008 memoir, The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement. The creek divided the rest of the town from the poor. He lived on “the wrong side” where his father was a Methodist minister serving poor whites.

Lucas Till is perfect in depicting Zellner’s likeness and soft-spoken demeanor.

For all the horror it shows, beatings of black people, near lynching of Zellner, it is straightforward and realistic, telling the daily travails of the movement and this rare local white activist. Based on my knowledge of Zellner and the SNCC people he interacted with, helped by my year as editor of the Mississippi Free Press in 1962-3, it is very accurate.

Maybe you know a lot about Martin Luther King Jr. You need to know about people like Bob Zellner. How did he get to that place? The trailer below shows Lucas Till as Zellner with his girlfriend (Lucy Hale) watching civil rights events on TV.

He explains, “My daddy was a minister. He was in the Klan. We went on a cultural exchange in the 30s to the Soviet Union. He hears a Baptist choir. It was a black choir. I was taken aback. They started singing beautiful sounds. We started traveling together. We went over a whole part of Russia. A terrible thing happened. I went color blind. I was ruined as a Klansman. Had to tell daddy. He didn’t want anything to do with robes for the rest of his life.”

But Zellner is pulled between his convictions and his self-interest, especially with acceptance at a northern university. His personal trajectory is a window that parallels the movement.

As a high school kid, he goes to a church meeting of the Montgomery Bus Boycott with other white students under the guise of doing research. Police surround the church, the attorney general attacks them, they are threatened with expulsion.

He goes to the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, a center for black and white activists. He is told, “We need somebody like a boy who can speak to white students throughout the South.”

He sees SNCC leader John Lewis on TV. He is challenged to join the Birmingham to Montgomery Freedom Ride.

You see old newsreels of mobs beating Freedom Riders, accusing them of being “Commies sent by the Kremlin.” (Even then it was “Russia Russia Russia!” Don’t the Russiagaters know their history?)

His girlfriend demands: “Do you want to jeopardize your life for some grand principle?” He does. Forget the northern college. He phones the office of SNCC. “I’m calling from Alabama, wondering if you need volunteers.”

“We could use you. How soon can you get here?” It was Chuck McDew, who was chair of SNCC, a very cool, smart, sophisticated northerner I met at the time and who would years later become a college professor in Minneapolis.

His grandfather (played by a gruff Brian Dennehy) is a Klansman who warns him against what he is doing on white campuses.

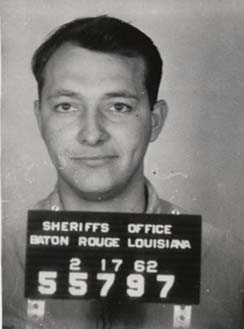

But Zellner goes to the Atlanta office and gets his instructions: “You will open the office, take messages, watch the briefcase.” That latter was a mystery! It seemed to have key movement contact information. In 1962, Zellner became the first white field secretary of SNCC. He’d be arrested and jailed 17 times in the next years.

The film continues with protests organized by the legendary Bob Moses of students marching and singing “Which side are you on.” It was based on a labor anthem. High school kids walking across a bridge: “I woke up this morning with my mind stayed on freedom.” New words to an old church song.

Zellner was targeted as a white traitor and beaten bloody. He was taken to a tree and a noose slipped around his neck.

The Klansmen argued about hanging him, but one pointed out that his minister father had gone to Bob Jones University and moreover, they would have trouble with the Feds, so they cut him down.

The film story ends before the real story ends. The film was shot on location in Alabama and, to show how things have changed, the credits give thanks for the support of the Alabama Film Commission, the mayor, top city officials, and the police department.

Zellner would go on to advocate for the rights of Native Americans on Long Island. Now in his early 80s, he has moved back to Alabama. Here’s what SNCC says about him today.

I must add that this film got an egregiously nasty review in the NYTimes, calling it “ideologically fraught” in current times! How dare there be a film about a white civil rights activist! The reviewer calls the depiction of the attempted lynching “tone deaf” because most lynching victims were black. “So, sorry, Zellner, delete that from your story.” In fact, delete your whole story, delete your amazing life.

And hail the ideological “cancel culture” which appears to believe that white people can never work together with black people for civil rights. Schwerner, Goodman and Cheney apparently didn’t exist.

For those who appreciate a fine and relevant film, cancel the ideological censors. See “Son of the South.”

Producers Colin Bates, Stan Erdreich, Bill Black, Eve Pomerance. Executive producer Spike Lee. Film website. Rent or buy on Youtube.