By Lucy Komisar

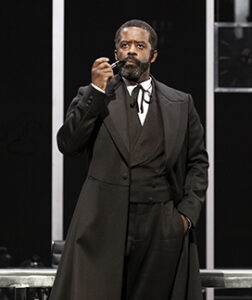

“The Lehman Trilogy” by Stefano Massini appears to be a love song to American capitalism, though if you look carefully, you will see some tarnishings and even betrayals. It starts with Henry Lehman (Simon Russell Beale), a German-Jewish immigrant, arriving in Montgomery, Alabama in 1844, nervous in his best black suit and coat.

Getting Americanized fast, he became Henry via an immigration official’s inability to write Heyum and opened a store to sell fabrics to the working class. There were only three colors, and people bought fabrics by the inch. Between that and the creation of the banking and trading empire Lehman Brothers is a fascinating tale told epoch by epoch through the lives of generations of Lehman men. (There are some women, but just wives and children.)

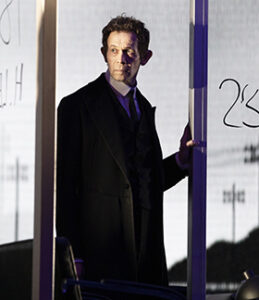

The play switches seamlessly, sometimes one sentence to the next, between narrative and dialogue, with the actors moving about a huge glass cube that rotates on the stage, lighted skylight panels at the top, with minimal furnishings that change through the eras – old fashioned offices are replaced with svelte ones, cardboard cartons have myriad uses — and scenes of the period in black and white photographs on the backdrop. The buildings will get taller, more modern. Es Devlin designed the set. Unobtrusive background music by Nick Powell is played by Candida Caldicot on a piano placed just below the stage on one side.

Henry Lehman expanded the dry goods business to sell farm implements to plantations. The 2019 production appeared to miss the fact of slavery as essential to cotton production, and the current script was changed slightly to make reference its role in the Southern system. But the Lehmans don’t take any moral positions here. It was capitalism.

During this time, Henry’s two younger brothers arrive. As if to make some amends, the director chose Adrian Lester, a black actor, to be Emanuel Lehman and later members of the family. He replaced the white Ben Miles who left to portray Thomas Cromwell in London. This was color-blind casting; there is nothing in the play to suggest Emanuel was not a white Jew from Bavaria. The third brother Mayer is performed by Adam Godley. All three are masterful in the roles. And Sam Mendes mounts a rich production so deftly that you are pulled into the characters and the times even as they change personae and decades.

The Lehmans knew how to take advantage of crises that afflicted others. When you see white smoke rising, it means plantations are on fire. Everything is lost, everything needs to be rebuilt. They get state financing to help the plantations survive and take a share of ownership. From there they become suppliers of cotton to northern manufacturers.

Yellow fever takes Henry. The Lehmans become brokers for cotton growers in other states.

Emanuel goes to the New York Cotton Fair. He finds a wife, the daughter of a man who introduces himself as “one of the richest Jews in New York.” The Jewish part is very prominent in the early Lehman stories, they become less observant as the generations pass, highlighted by the decreasing attention paid to mourning rituals.

When the Civil War breaks out, plantations burn, sales to the North stop, and the cotton is sold to Europe. After the war, the Lehmans propose that Alabama give them money to invest in rebuilding, and they get millions in capital, setting up the Lehman Brothers Bank of Alabama.

But the South is not where the action is, and Emanuel insists they go to New York. The signs change at the Lehman Brothers Bank. There’s a board room. Talk is bigger. Herbert Lehman (Lester) joins the New York Stock Exchange.

Another son, Philip (Beale), invests in railroads and oil, he wins bets on tobacco. He wants seven zeroes profit. He says Lehman Brothers’ success is not based on luck, it’s strategy.

And that applies to his personal life. In his journal, he discusses marriage. He does sexist ratings of the women he might wed. Lester and Godley play the prospective brides. The perfect wife is not a feminist! The three actors are good at playing wives and children, albeit the depictions are a bit hokey.

Mayer’s son Herbert as a child “has a big problem with the idea that a brother is worth more than a sister…Herbert Lehman wanted things to be fair, and in the world in which he found himself, that meant he would always have a problem.”

He goes into finance instead of banking and then to politics. He would become governor and then senator of New York, the greatest Lehman, marked by a morality the others eschewed.

Robert (Bobby) Lehman goes to Yale, travels in Europe, buys art, and wants to bet on entertainment, on movies

There is another sign change. The Lehman Corporation turns to pure finance. And then October 1929 happens.

Black Thursday, panic hits Wall Street. People say “Give me my money.” There is no money. Stockbrokers in white suits and ties jump out of windows.

Lehman Brothers has lost all value. But Mayer notes that other banks will go bankrupt, and the state will let certain banks fail.

He says: “The state will let the first banks fail, won’t lift a finger. They need to look like they aren’t helping. It’s in Lehman’s interest that certain banks close. It’ll give the sense that the chaos is at its peak, that some rotten apples needed to be dealt with, that things can only improve.

That’s why we shouldn’t help the other banks in crisis: if they ask for loans, we should say no. The state will do the same. After that first moment, the state will need strong banks and they’ll help us. If we can survive the first month, they won’t let us fail.”

He adds, “Regulation will be the cost.” (The morality of capitalism. Remember that about letting banks fail 80 years later!) And regulation by the agencies the banks control will be fake.

There’s a curious diversion to a diner in Nebraska run by a Greek named George Petropoulos, who changes it to Peterson. He teaches his son Pete mathematics by getting him to do the accounts.

The corruption of the system is evidenced by Lester as a marketing director from Mississippi. It’s the only time race matters, as he is described as the product of a segregated school who now stands in the board room. He declares, “People will give us money they don’t have for what they don’t need…. Everyone will borrow, everyone will buy, and we will become all powerful.” They bet on computers.

Bobby restructures the bank. He wants to invest in King Kong and TV. And after Pearl Harbor, Lehman Brothers will invest in war, “Lehman invests in arms, and it pays off.” They are miffed at the upright Lehman, now a senator: “Herbert Lehman is killing us with these regulations.”

But they survive and expand globally. They celebrate their success. But it’s now a stock company and new board members are promoting changes.

Fast forward, in 1973, the new president of the bank will be Pete Peterson. No more Lehmans at the top. Peterson had just come from serving as Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Commerce, 1972-3. He’d be chairman and CEO of Lehman Brothers 1973–1977 and Lehman Brothers, Kuhn, Loeb 1977–1984.

Lew Glucksman, son of a Hungarian, is a master at manipulating stocks and proposes to create a trading division. “You won’t be able to show us off in the living room.” It is set up on Water Street, on the Lower East Side apart from the financial district, long tables with computer screens and Chinese takeout. The partners hate him. His protégé will be Dick Fuld.

He will offer Peterson millions: “Give me the bank and you’ll have it tomorrow.” Reply: “It’s a deal. Lewis Glucksman, You’re the new president.”

A year later, with the cash, Peterson co-founded the multi-billion-dollar private equity Blackstone Group. Under a misnamed Bill Clinton entitlement and tax “reform” commission, he called for cuts in social security for ordinary folks. He set up a foundation to promote the retrograde idea, but it didn’t fly. Spreading his largesse, he would become chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations. That’s where I met him, as right-wing as ever. This is just to point out that as corporations took over the government, they brought with them the self-interest of the market.

In September 2008 there was another financial crash. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, who had close ties to Lehman’s competitor Goldman Sachs, said no government money would be sent to save Lehman. Fuld would claim that the firm was a victim of organized naked short selling (selling stock the traders didn’t own and never obtained to send to buyers) that destroyed its stock even as it had cash stashed elsewhere. (For more on naked short selling, go here and here.)

So, the Lehmans and their international financial behemoth were eaten by the amoral and routinely corrupt system that produced them. A brilliant and fascinating play and production.

“The Lehman Trilogy.” Written by Stefano Massini, adapted by Ben Power, directed by Sam Mendes. Nederlander Theatre, 208 W 41st St. New York City. (877) 250-2929. Three acts; runtime 3:15. Opened Oct. 14, 2021, closes Jan 2, 2022. Review on New York Theatre-Wire.