By Lucy Komisar

British playwright-director Robert Icke is fast becoming one of the most important English-language theater makers. Taking the anti-Semitism at the center of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1912 play “Professor Bernhardi” to illuminate today’s identity madness, he has created an essential work.

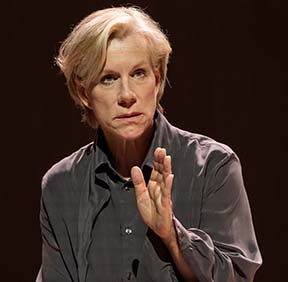

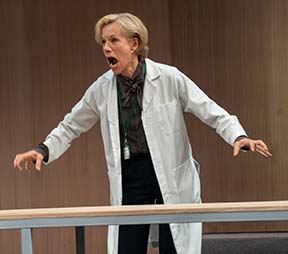

Ruth Wolff (a brilliant Juliet Stevenson) attacked as a Jew, declares “No, I am a doctor.” Wolff is tough bordering on aggressive. (Schnitzler’s Jew was a man.)

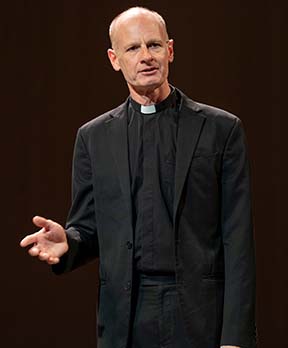

The Jewish issue is raised when Wolff denies the demand of a Catholic priest (John Mackay) to give last rites to a 14-year-old patient dying of sepsis from an abortion caused by taking pills she got online. Ruth thinks, “If they’d let her have a supervised abortion in a medical setting, she’d be eating ice cream now and surfing the internet.”

The priest says, “She was born in mortal sin without being forgiven.” Wolff declares the girl never asked for the priest and has the right to a peaceful death, not (it is understood) to be “forgiven” (abused) for anyone’s “sin.” (The parents are abroad and cannot give consent.)

There’s a bit of a verbal confrontation, and as the priest pushes past Wolff, she touches his shoulder. “Assault!”

The woman is a brilliant medical scientist and founder of the research institute where the girl was brought. She is being targeted by jealous white male Catholic doctors, Murphy (Daniel Rabin) and Hardiman (Naomi Wirthner) who want to give a position to a less qualified black male while she wants the superior candidate, a Jewish woman. No indication they care about blacks; they clearly don’t want a Jewish woman.

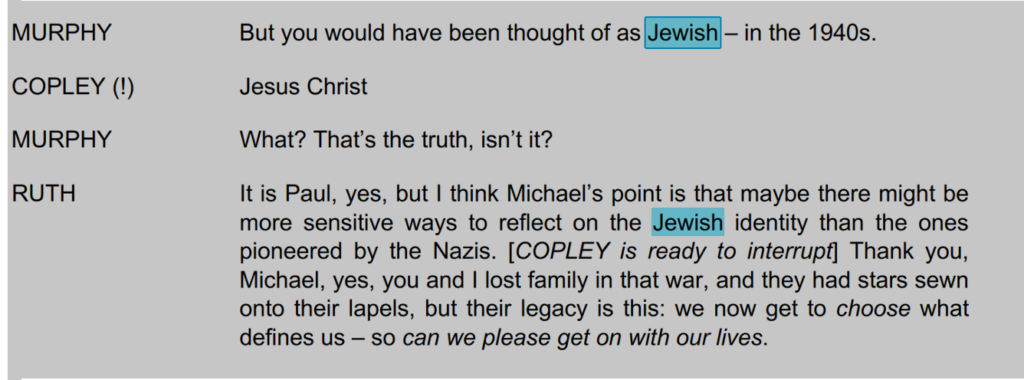

When the Catholic doctors point to her Jewishness, she notes that her parents were Jewish, “they were religious people,” she is not. Murphy brings up the Nazi definition and Doctor Copley, also Jewish, intervenes.

It is a smart turnabout by Icke. When people were defined by groups, instead of treated as individuals, it led to anti-Semitism, which in the years after Schnitzler’s prescient play, led to Naziism. Identity politics by the Third Reich.

Then she fights social media attacks when Catholics and anti-abortionists raise a multi-thousand internet petition over her refusal to allow the priest into the dying girl’s room. She appears bravely before a TV panel that in broad satire (which these days might not be recognized as satire), includes an anti-abortion lawyer, a “Creation Voice” activist, a “post-colonial” black academic and (wait for it) a researcher of unconscious bias!

The black woman condemns her for being white. It shows the corruption of identity politics. The obvious point is that the members of this phalanx, who would turn violently against each other when they had the chance, agree that a strong independent voice is the enemy. As indeed it is.

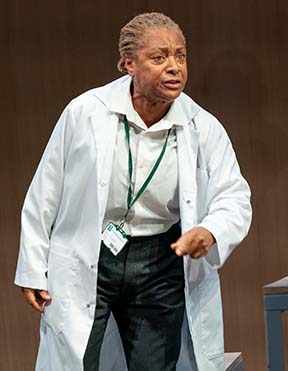

Meanwhile, the institute is trying to raise money for a new building. “We bow to this and we’re putting religion above medicine,” says Cyprian (Doña Croll), the clinical director. Well, of course they do. These Catholic doctors consider lives less important than cult. And maybe cash? But Wolff, of course, has integrity, a rare quality among her colleagues.

I like Icke the writer’s script, but disagree with Icke the director’s production. He takes the notion of canceling identity too far. The script includes this:

The text says the priest is black. The actor is white. That doesn’t challenge the notion of identity, it just confuses the audience.

Casting a white man for a black woman or a black man for a white woman (and all the permutations) is bad when race and gender matters in the text. Or do we want to bring back black face? And white face? Flint is the Minister of Health who had promised to fund the new building. Logically, why can’t a black male actor play her? How about getting some children to play adults, just to mix it up?

On the same line, there’s that apparition of a black woman (or man?) at Wolff’s home to represent the ghost of her dead “partner,” Charlie (Juliet Garricks).

At first, I couldn’t figure out who that was supposed to be, who Ruth was hallucinating or calling up from memory. Then I got a closer look at Charlie. Black female. I don’t have to be told. I just focus my lying eyes.

There is also a character, Ruth’s friend Sami (Matilda Tucker), a young woman who identifies as a boy. Or maybe the other way around, doesn’t matter. Not clear why she/he is there.

For a play to object to the current “fluid identity” politics and then to cast people not of the same sex or color as the character they play is quite contradictory. Casting should care about clarity. You don’t want the audience to keep thinking, “Well, who is that supposed to be?”

There’s no place, because we don’t know who this is. The male Doctor Hardiman, who appears sexless, is also played by a woman (Naomi Wirthner). I thought the actor was a man, but because of her body shape, you hardly notice. Were the castings to make a point or to give jobs to female actors?

More central to the text, a main problem is that Wolff is so tough, it is out of character for her not to keep fighting. But perhaps Icke has to show that the best, most brilliant, most ethical people, who don’t check which way the wind is blowing before they take a position, can be destroyed by the viciousness of identity politics. And that indeed is true.

“The Doctor.” Adapted by Robert Icke from Arthur Schnitzler’s “Professor Bernhardi” and directed by Icke. Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue between 66 & 67th Streets, NYC. Runtime 2hrs25. Opened June 14, closes Aug 19, 2023.