By Lucy Komisar

Oct 29, 2023

I wrote about Israeli apartheid over 40 years ago. I visited Israel and the West Bank in 1981. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat had just been assassinated, though my visit had been planned before that. First I went on a trip organized for journalists by the Israeli government. Then, believing I hadn’t been shown the full story, I went months later on my own. This is what I wrote for The Nation, prescient in the title, “The West Bank as Bantustan.”

Curious that the only archive where I could find it was the Palestinian Museum. It had it in the Palestine National Theatre collection, because it was cited by a Palestinian theater director who noted a section I wrote about an East Jerusalem company doing political theater.

Here is the museum’s story link and the citation. Printed text is below the graphic which shows the director’s marking of the section about the theater troupe.

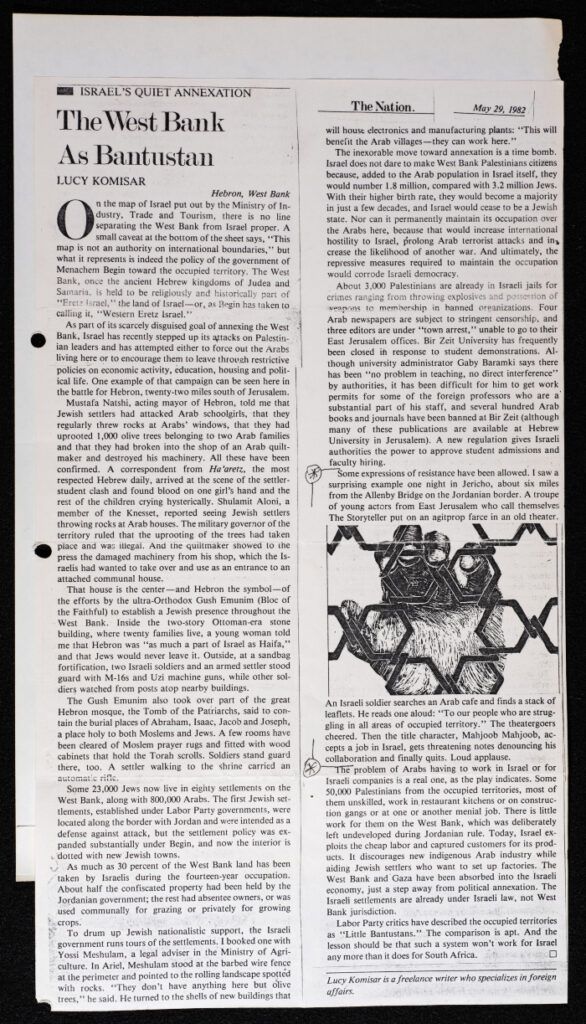

The Nation, May 29, 1982: “The West Bank as Bantustan”

Hebron, West Bank

On the map of Israel put out by the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism, there is no line separating the West Bank from Israel proper. A small caveat at the bottom of the sheet says, “This map is not an authority on international boundaries,” but what it represents is indeed the policy of the government of Menachem Begin toward the occupied territory. The West Bank, once the ancient Hebrew kingdoms of Judea and Samaria is held to be religiously and historically part of “Eretz Israel,” the land of Israel—or, as Begin has taken to calling it, “Western Eretz Israel.”

As part of its scarcely disguised goal of annexing the West Bank, Israel has recently stepped up its attacks on Palestinian leaders and has attempted either to force out the Arabs living here or to encourage them to leave through restrictive policies on economic activity, education, housing and political life. One example of that campaign can be seen here in the battle for Hebron, twenty-two miles south of Jerusalem.

Mustafa Natshi, acting mayor of Hebron, told me that Jewish settlers had attacked Arab schoolgirls, that they regularly threw rocks at Arabs’ windows, that they had uprooted 1,000 olive trees belonging to two Arab families and that they had broken into the shop of an Arab quiltmaker and destroyed his machinery. All these have been confirmed. A correspondent from Ha’aretz, the most respected Hebrew daily, arrived at the scene of the settler-student clash and found blood on one girl’s hand and the rest of the children crying hysterically. Shulamit Aloni, a member of the Knesset, reported seeing Jewish settlers throwing rocks at Arab houses. The military governor of the territory ruled that the uprooting of the trees had taken place and was illegal. And the quiltmaker showed to the press the damaged machinery from his shop, which the Israelis had wanted to take over and use as an entrance to an attached communal house.

That house is the center—and Hebron the symbol—of the efforts by the ultra-Orthodox Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful) to establish a Jewish presence throughout the West Bank. Inside the two-story Ottoman-era stone building, where twenty families live, a young woman told me that Hebron was “as much a part of Israel as Haifa,” and that Jews would never leave it. Outside, at a sandbag fortification, two Israeli soldiers and an armed settler stood guard with M-16s and Uzi machine guns, while other soldiers watched from posts atop nearby buildings.

The Gush Emunim also took over part of the great Hebron mosque, the Tomb of the Patriarchs, said to contain the burial places of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph, a place holy to both Moslems and Jews. A few rooms have been cleared of Moslem prayer rugs and fitted with wood cabinets that hold the Torah scrolls. Soldiers stand guard there, too. A settler walking to the shrine carried an automatic rifle.

Some 23,000 Jews now live in eighty settlements on the West Bank, along with 800,000 Arabs. The first Jewish settlements, established under Labor Party governments, were located along the border with Jordan and were intended as a defense against attack, but the settlement policy was expanded substantially under Begin, and now the interior is dotted with new Jewish towns. As much as 30 percent of the West Bank land has been taken by Israelis during the fourteen-year occupation. About half the confiscated property had been held by the Jordanian government; the rest had absentee owners, or was used communally for grazing or privately for growing crops.

To drum up Jewish nationalistic support, the Israeli government runs tours of the settlements. I booked one with Yossi Meshulam, a legal adviser in the Ministry of Agriculture. In Ariel, Meshulam stood at the barbed wire fence at the perimeter and pointed to the rolling landscape spotted with rocks. “They don’t have anything here but olive trees,” he said. He turned to the shells of new buildings that will house electronics and manufacturing plants: “This will benefit the Arab villages—they can work here.” The inexorable move toward annexation is a time bomb. Israel does not dare to make West Bank Palestinians citizens because, added to the Arab population in Israel itself, they would number 1.8 million, compared with 3.2 million Jews. With their higher birth rate, they would become a majority in just a few decades, and Israel would cease to be a Jewish state. Nor can it permanently maintain its occupation over the Arabs here, because that would increase international hostility to Israel, prolong Arab terrorist attacks and increase the likelihood of another war. And ultimately, the repressive measures required to maintain the occupation would corrode Israeli democracy.

About 3,000 Palestinians are already in Israeli jails for crimes ranging from throwing explosives and possession of weapons to membership in banned organizations. Four Arab newspapers are subject to stringent censorship, and three editors are under “town arrest,” unable to go to their East Jerusalem offices. Bir Zeit University has frequently been closed in response to student demonstrations. Although university administrator Gaby Baramki says there has been “no problem in teaching, no direct interference” by authorities, it has been difficult for him to get work permits for some of the foreign professors who are a substantial part of his staff, and several hundred Arab books and journals have been banned at Bir Zeit (although many of these publications are available at Hebrew University in Jerusalem). A new regulation gives Israeli authorities the power to approve student admissions and faculty hiring.

Some expressions of resistance have been allowed. I saw a surprising example one night in Jericho, about six miles from the Allenby Bridge on the Jordanian border. A troupe of young actors from East Jerusalem who call themselves “The Storyteller” put on an agitprop farce in an old theater. An Israeli soldier searches an Arab cafe and finds a stack of leaflets. He reads one aloud: “To our people who are struggling in all areas of occupied territory.” The theatergoers cheered. Then the title character, Mahjoob Mahjoob, accepts a job in Israel, gets threatening notes denouncing his collaboration and finally quits. Loud applause.

The problem of Arabs having to work in Israel or for Israeli companies is a real one, as the play indicates. Some 50,000 Palestinians from the occupied territories, most of them unskilled, work in restaurant kitchens or on construction gangs or at one or another menial job. There is little work for them on the West Bank, which was deliberately left undeveloped during Jordanian rule. Today, Israel exploits the cheap labor and captured customers for its products. It discourages new indigenous Arab industry while aiding Jewish settlers who want to set up factories. The West Bank and Gaza have been absorbed into the Israeli economy, just a step away from political annexation. The Israeli settlements are already under Israeli law, not West Bank jurisdiction.

Labor Party critics have described the occupied territories as “Little Bantustans.” The comparison is apt. And the lesson should be that such a system won’t work for Israel any more than it does for South Africa.

The Citation

Thanks for finding this copy of your 1982 article. It is easy to follow the ideas; and always good to have viewpoints from journalists who visit a place during an important point in history.

Pingback: Queens College president had police waiting at gates during commencement : The Komisar Scoop