By Lucy Komisar

InsideParadeplatz (Zurich)

Aug 10, 2024

which validates news stories the mainstream and “alternative” press ignore, has cited this article, noting “UBS has actively sought to suppress media coverage of the case. The bank has stated that it does not want journalists at the hearings, and no other sources have covered this story.”

A couple in the Bahamas claims that UBS scammed them by taking their money and making fictitious trades into U.S. markets. Some of the documents they supply show money going in and out of their account for securities trades. But UBS repeatedly refused to supply required trade confirmations from the American brokers.

The couple speaks volumes about their charge and UBS declines to comment, saying only, “We believe these allegations have no merit.” And they have spent ten years fighting in court to block a trial on the merits.

The evidence is strong that UBS Bahamas was abusive toward these retail clients and that the Bahamas court system is corrupt.

Yuri and Irina Starostenko, Italian citizens living in the Bahamas, allege that UBS Bahamas defrauded them by promising to execute trades on their behalf in U.S. markets and taking their money but not making the trades. They gave the court the documents they had, but can’t get the UBS documents they say could prove their claims. That is because UBS has blocked them from having their day in court, which would give them “discovery” – the right to demand the documents. Why would UBS want to keep the Staros’ trade documents secret?

- UBS is the largest private bank in the world. It has been found guilty of felonies by western governments numerous times.

- In 2012, UBS Bahamas offered them a loan deal to provide cash for investments.

- From June-September 2013, the couple placed 252 trade orders into U.S. markets, but UBS failed to provide confirmations required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that the trades were executed.

- In 2018-2019, after litigation, UBS provided internal documents purporting to show the trades, but they did not include required confirmations from U.S. brokers proving the trades occurred.

- An affidavit from a UBS official in 2019 admitted it had no other trade records.

- A New York lawyer who specializes in suing big banks said that “confirms” should show up in trading accounts under “statements.” If they aren’t provided, it’s because a firm didn’t execute trades.

- The dispute continues in the Bahamas courts where judges’ delays were condemned by a chief justice. In the latest, June 19th, the judge cancelled a hearing that should have granted the Starostenkos a trial date.

- The Starostenkos also sued UBS in U.S. court for securities fraud. UBS got the suit in the U.S. dismissed on jurisdictional grounds, but the couple filed an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- The story raises the question of why UBS would pay millions of dollars over a decade to a well-connected law firm (a partner sits on the stock market regulator board) for a minor case brought by a day-trading couple.

- Financial regulators and prosecutors in the Bahamas, Switzerland and the U.S. have not investigated the couple’s claims.

THE STORY

Under the swaying palms of Lyford Cay is evidence of an illicit world of fake stock trades and fleeced investors. This exclusive Bahamian gated community, home to titans like the Mellons and Bacardis, welcomed Yuri Starostenko and Irina Tsareva, born Russian, now citizens of Italy. .

The Starostenkos’ story begins with a wartime saga. Irina Tsareva’s Jewish mother survived WWII Odessa, her identity hidden by a grandmother’s fictitious marriage. Yuri’s family fled Siberian repression.

The families in the West might be called middle class. Irina says, “My grandpa Valdimir Isaakovicth Litvak taught in the ship engineering department of Odessa National Maritime University and lectured all around the USSR.” She says her grandfather fought in the Russian army against the Nazis and that her mother survived the German occupation of Odessa, because her grandmother bought fake documents and made a fictitious marriage to a Polish man who claimed her mother was his daughter and hid her for two years in a village house, because the three-year-old had Jewish looks. Her family name is Tsareva.

Irina Tsareva says, “Yuri’s family were on his mother’s side Jewish merchants from the Urals and on his father’s side Belarusian kulaks (farmers). Both sides of the family went to Siberia escaping famine and repression. The kulaks lost their lands in the 1920s, and his grandfather was sent to prison in Siberia. He wife followed to be near him. His father taught at a coal institute and worked in mines; his mother was a head of a police department of their city.”

After the Soviet empire collapsed, the couple left Russia in the 1990s, drifted west, became citizens of Italy, and found their footing in Belgium, where they say that in the years of stock boom they did well in the Russian securities market. In 2007, they moved to the Bahamas to raise their five sons, ages one to nine; the next year, a sixth son was born.

Lyford Cay is an enclave whose prominent residents have included Henry Ford II, Aga Khan IV, Prince Rainier III of Monaco, Huntington Hartford II, Babe Paley, the Bacardis, and the Mellons, who have a family estate with 200 feet of white sand beach. In 1962, when President Kennedy was in Nassau for private meetings with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, he stayed at the home of Canadian brewery tycoon E.P. Taylor, and Macmillan was next door.

Lyford Cay, with yachts bobbing in the marina and ice clinking in the clubhouse, felt like paradise. Built in the late 1950s by Taylor, it has about 450 luxury villas, restaurants, a marina, a golf course and beaches. The Starostenkos bought a 2-story, 5-bedroom house with a guest cottage, swimming pool and garden for $2.4 million.

The couple had no papers to work locally, but they could trade. They became clients of Credit Suisse AG, Nassau Branch in 2008. Four years later they switched to UBS Bahamas Ltd. lured by the promise of easy profits through trading U.S. stocks. UBS offered a $1.4 million loan, their home as collateral, half deposited into an investment account.

UBS, the world’s largest private bank, operates in over 50 other countries, in all major financial centers. It has a checkered past. In 2008, U.S. Senate investigators reported how it used code names and encrypted computers to help hundreds of rich Americans evade multi-millions on taxes. Just a year later, UBS agreed to pay $1.56 billion to the U.S. for failing to report about 14,000 foreigners’ trades of U.S. registered securities and paying the required withholding tax. Since then, UBS must report all trades in U.S. securities to the IRS. In 2012, the U.S. fined UBS $1.5 billion for manipulating Libor and other benchmark interest rates.

Did missing confirmations mean fictitious trades?

From 2013 to 2014, Yuri Starostenko feverishly placed over 200 stock orders on U.S. markets. Under U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules, records should have contained trade confirmations from U.S. brokers, proof the trades were executed as ordered on NYSE or Nasdaq. It should have come from UBS Financial Services, which handled the Bahamas orders. Instead, that never happened. “We never received a single confirmation,” Irina Tsareva said, “despite endless requests.” (Irina is the talkative one, speaking at court hearings. Yuri does the legal research and writes the filings for their pro se legal actions. They do not have a lawyer.)

The Starostenkos protested to their broker that they were not getting confirmations. At an October 2013 meeting, the UBS account manager cryptically claimed lawyers would need to approve providing confirmations, a violation of SEC rules that traders are entitled to them. Red flags snapped in the tropical breeze. Why the stonewalling over standard documents?

Even more alarming to them, Kevin Price, the head of UBS’ Bahamas trading desk, had from 1994-1998 worked in the U.S. for fraudster Bernie Madoff, who built his Ponzi scheme on phantom trades. Later, in 2013, when Price worked for UBS Bahamas and handled the Starostenkos’ trades, he also worked for UBS Financial Services, which was supposed to send the confirmations.

Why had they believed UBS’s promises?

Ironically, the Starostenkos were victims of the myth of western capitalism imbibed in the communist Soviet Union. Irina Tsareva said, “We were raised, especially my social group, academics, with a deep admiration for the West, where the U.S. is the apex of all good and Swiss banks are examples of honesty, truth — you can trust them as the elite honest holders in affairs. Basically, if you have a bank account in Switzerland, you are resident in paradise.”

On October 2, 2013, UBS provided a list of 204 trades, dated Sept 19, 2013 for the trades executed on June-September 2013, which it called trade confirmations but included no confirmations from U.S. brokers. The money credit and debited for particular trades does show those trades were recorded. But were they actually made?

The Loan

UBS held a trump card, the loan in which the bank lent them $1.4 million in exchange for collateral of their home, worth $2.8 mil in 2012 according to the appraisers engaged by UBS. Half would be in a trading account, half in a cash account which they put in another bank. But the card was a Joker. UBS, which was an offshore bank allowed to provide services for foreigners, had obtained a license from the Central Bank to give mortgages to foreigners for second homes. However, the loan was made to the Starostenkos eight months earlier, and they were permanent residents. The mortgage deal was not allowed by the bank’s license.

In November (2013), after their account dipped below the required $700K and following their protests about lack of “confirms,” UBS sent them a letter demanding they pay back the loan. Both sides’ numbers differ slightly, but they agreed the investment account dipped below $600K.

Irina Tsareva says they didn’t use money from the cash account at the other bank to cover the trading shortfall on grounds they didn’t have to abide by the $700K agreement, because UBS was not providing promised services, that they would have not defaulted if not for $138K of damages due to UBS “breaches” in handling their securities: late executions and fictitious trades.

She said, “Because we already spend one year battling with UBS for proper execution of our trades, instead of topping up the account, we requested UBS refunds.” They could have withdrawn from the deal, but then they would have had to pay back the $1.4-million loan. The Starostenkos also claimed that the $700K loan clause did not govern relations between the parties because the UBS had never invoked it. But whatever the merits, they didn’t get a chance to argue in a Bahamas court whose judges have denied them a trial.

Appeal to UBS Zurich

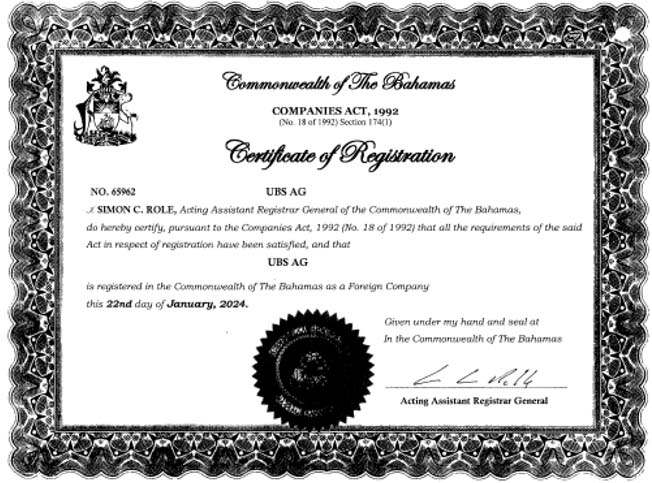

UBS Bahamas is owned by UBS AG Zurich, which has more than 200 companies in the U.S., including UBS Financial Services which handles trading and private wealth management and UBS Securities which is the investment banking division.

By 2014, the Starostenkos were convinced they were being scammed. They contacted UBS’s Zurich headquarters, pleading with the assistant of CEO Sergio Ermotti for help. Irina told of the lack of confirmations for the months of trading. Headquarters repeated the company response – UBS acted properly. Sasha Savic, UBS chief of staff for Latin America & Caribbean replied, “We have investigated this matter, and are satisfied that the Bank and its personnel have acted properly in relation to your matter and we cannot find any basis for your position.” In April 2023, Ermotti, who had left the company, would be brought back to head UBS in the merger with Credit Suisse.

On January 30, 2014, Irina Tsareva again requested confirmations and explained to Fabio Jenny, manager at UBS Bahamas and second after the CEO, that the records provided were not confirmations, but UBS accounting slips. Jenny said “thank you for the reminder. We will be in touch with you shortly”.

The Loan

The meeting was scheduled for March 12, but on February 28, Yuri Starostenko received a letter from UBS’ lawyers Lennox Paton demanding the immediate repayment of the entire loan. Lennox Paton is well-connected. It was the registered agent in the Bahamas for Bernie Madoff. Brian Sims, the principal partner, was chosen by the Securities Commission of the Bahamas to be liquidator of FTX, the company of convicted fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried. Another partner, Michael Paton, sits on the board of the Commission, with authority over UBS’s compliance with trading rules.

The Trades

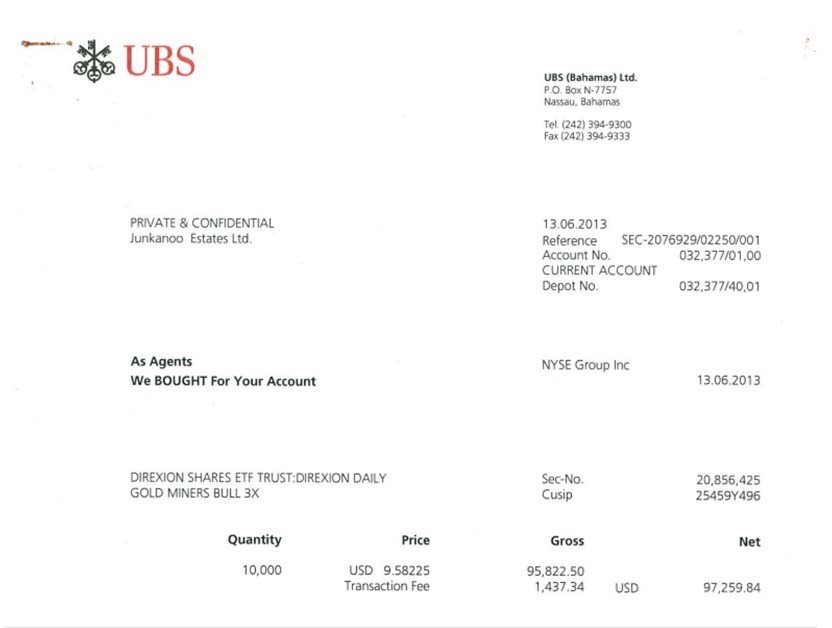

Meanwhile, on February 28, 2014 the Starostenkos also received from UBS 205 sheets delivered for trades from June 13, 2013 to September 18, 2013. It included 199 trade advises. It lists buys and sells of the same securities on the same day to be flat at end of day. It was part of their trading strategy because UBS did not have “stoploss” service to automatically sell if securities suddenly went sharply down.

Here is a first page:

UBS loves the Bahamas and then it doesn’t

In 2012, UBS Wealth Management Division CEO Jürg Zeltner told “The Bahamas Investor” that the Bahamas was an attractive, international financial and booking center, “especially in terms of wealth structuring– in particular the trust business.” He said “the beauty” was that it is offshore but close by. He said UBS’s strategy for the Bahamas was “to grow.” And to be “globally compliant,” meaning “transparent.” He added, “The world has agreed to a new, level playing field which The Bahamas is part of. That makes it stronger, because it complies and, if it had not, then I think there would not be too much of a future.”

Less than two years later, UBS liquidated its Bahamas operation. On March 7, UBS told the Securities Commission of the Bahamas that it was “winding down the banking side of its operations over the next year.” That included trading. In fact, it was going into voluntary liquidation. No reason was given, but it avoided dealing with new rules that would have revealed that its traders were not registered (only the CEO and compliance officer were registered), and it removed out of the country officials who could have been readily called to testify in the Starostenkos’ suit.

Curiously, the minutes of a meeting of March 18, disclosed by UBS during the lawsuit discovery process, says “client follow-up trade confirmations requested some weeks ago” and at the bottom ” trade confirmation to client – legal to sign off.” But it was not just “legal,” which UBS Bahamas officials should have known, the denial was illegal under U.S. law for trades on American exchanges. And U.S. law enforcers cast a wide net, not stopping at the border.

The Loan

On April 11, 2014, UBS Bahamas appropriated from the trading account a claimed balance of more than half a million ($525K.) In October, it sued the couple for falling below $700K minimum to be kept on the account. It repeated the demand they forfeit the home they had bought for $2.4 million and which assessments showed had increased in value to near $4 million. After UBS accused the Starostenkos of being in default on the loan, they filed a counterclaim. The cases were joined and neither has been heard, with the trial postponed since 2015 and without a new date appointed.

The Starostenkos say that absent proof of the trades, $204K should be refunded with interest. The couple has copies of emails showing real buys and sells with UBS replies. Here are copies of emailed orders Aug-Sept 2013. And UBS’s acknowledgement of trades. Many showed profits. Irina Tsareva insists the trades were never executed and that UBS took its own cash to cover the gains. But she has no proof, because she can’t see UBS accounts.

And UBS does not want “discovery” on that issue. Lead lawyer Marco Turnquest did not reply to the query: “Can you provide evidence that the trades the Starostenkos made were actually sent to U.S. exchanges in spite of the fact the UBS Bahamas refused to send them trade confirmations? Is there a reason UBS Bahamas refused to send the confirmations in spite of numerous requests?”

After several years of legal maneuvers, on Feb 27, 2018, a team sent by UBS lawyers forced the Starostenkos out of their home. The video. The family depended on friends to house them. They would become eligible for food vouchers. The failure to top off the loan shortfall had a disastrous end.

One of team sent to evict the Starostenkos grabs teenage son, Teo. From the video.

The Starostenkos had been struggling to get a trial on the 2014 case. The judges granted numerous UBS petitions for delay. Then, in 2018, Supreme Court Chief Justice Ian Winder delivered a ruling that a trial would take place the next year. That the discovery, the stage when the parties can claim access to the other’s documents and proofs, should be concluded by August 2018. That expert witnesses’ statements would be filed April and May 2019 and a trial would occur Sept 23, 2019.

Meanwhile, November 1, 2018 they received an email from the Securities Commission of the Bahamas confirming that only two UBS executives but none of the persons executing their trades was licensed.

The Trades

For a hearing November 12, 2018, the Starostenkos asked that UBS produce trade confirmations. Instead, UBS arrived with a surprise application for sale of the Starostenkos’ home “to cover costs” for $1 million, claimed in an affidavit by a partner of the UBS liquidator, a realtor, while the house had been appraised at more than three times that value, at $3.6 million, in December 2017.

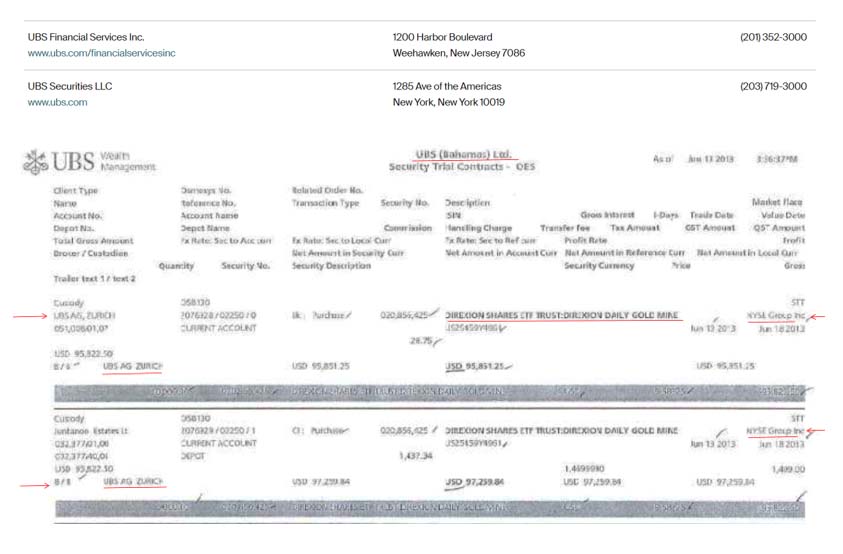

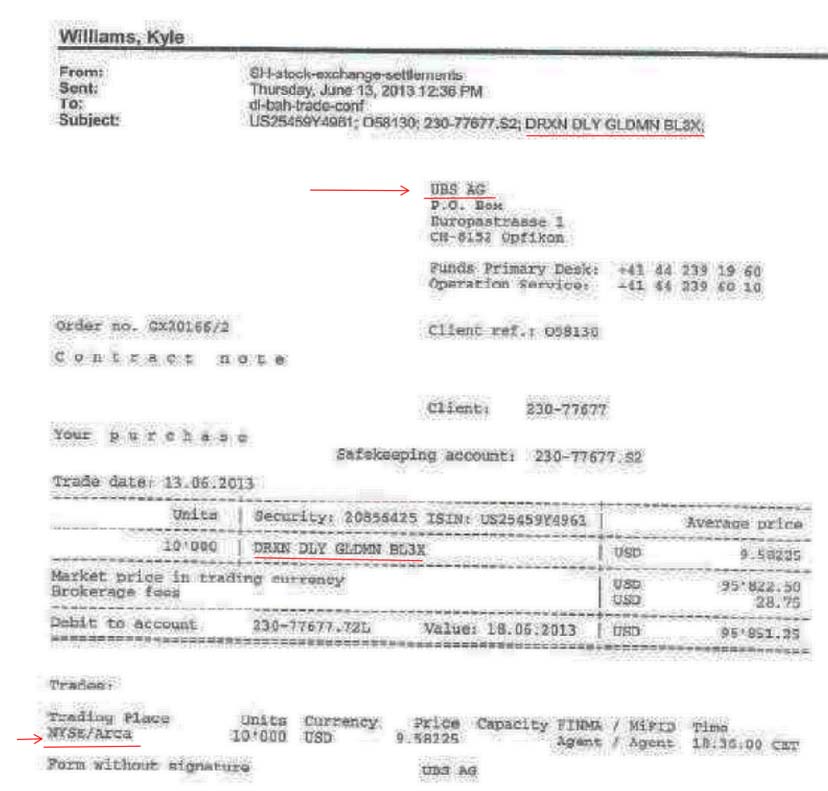

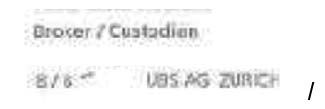

The bank on November 7, 2018 provided a second set of documents, dated December 31, 2013 which were individual pages that showed 51 trades with “Securities Trial Contracts” from UBS Wealth Management indicating a trade handled by UBS Bahamas (dated June 11, 2013) and related “Contract Notes” from UBS AG Zurich (dated June 13, 2013) about the same trade.

Document showing the UBS connection to the Bahamas trades into the U.S. markets.

Dr. Susanne Trimbath, who worked for the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), the U.S. national clearing agency, and is a consultant on stock settlement and author of several books on the stock market, explained, “Every broker/firm has its own system to produce these customer documents. As a rule, what they send to/from the SROs [self-regulating organizations] is consistently formatted (SROs dictate the file layouts).”

Looking at the document, she said, “UBS AG Zurich is the custodian; they don’t appear to reveal the broker-dealer unless those first 3 symbols (can’t read) before ‘UBS AG Zurich’ is the broker. The column header indicates ‘Broker / Custodian’ for that line.”

She said, “The document header is ‘UBS Wealth Management. The document indicates that the shares were 1) held by UBS AG Zurich as custodian [probably after receiving them from the broker since the $28.75 commission shows there] then 2) moved to Junkanoo Estates Lt. [the Starostenkos’ company. Irina Tsareva said they chose the name of a Caribbean folk festival they witnessed on their arrival to pay tribute to the Bahamas.] The second section is the same as the first with the exception of the addition of the $1,437.34 UBS commission. The final message confirms that $28.75 was the broker’s fee (the UBS fee would be an advisory fee).”

“So, to me it says the trade was done on NYSE but by ‘another broker-dealer.’ If UBS Wealth Management trades as principle, it doesn’t go to an exchange but takes shares from their own inventory. She concluded, “None of the documents say that UBS Financial Services executed the trades on NYSE. Even the internal documents only show UBS AG was the agent, not the broker.”

To reprise, here are the documents on alleged confirmation UBS provided

1 On October 2, 2013, UBS provided a three-page list of 204 trades, dated Sept 19, 2013 for the trades executed on June-September 2013.

2 On February 28, 2014 the Starostenkos received 205 sheets delivered by George Maillis for trades from June 13, 2013 to September 18, 2013. It included 199 trade advises. (205 pages)

3 On November 7, 2018, they got a UBS account statement with 51 “Contract Notes” and related 51 “Securities Trade Contracts,” documents the bank created. (121 pages) It mentioned UBS Bahamas, UBS Wealth Management and UBS AG Zurich. See this.

4 On December 13, 2018, they got a UBS December 31, 2013 Account Statement for 2013, containing listings of 205 cash transactions and 202 security transactions. (23 pages) See this. Opening is from the first page of the ‘Cash Transactions’ section of the statement shows a $617.8K balance, the last page shows a $557.7K closing balance, a loss of about $60K.

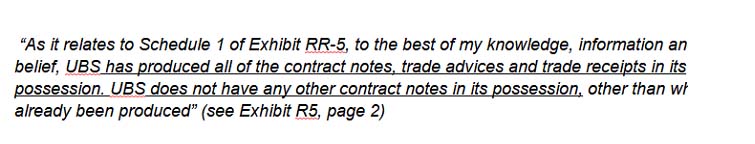

At a hearing February 21, 2019, UBS told the judge that trading advises are regular documents for trading in NYSE. Following the Starostenkos’ insistence that the papers UBS had provided were not confirmations and after UBS’ attorneys said that they produced all in their client’s possession and had no other documents, Judge Ian R. Winder said, “I will make the order that your client produce an affidavit in the very terms that you’re representing to me now.” He ordered UBS to swear an affidavit that it did not have other documents.

Then, a UBS executive confirmed that after extensive searches, no other documents could be located. The March 7, 2019, affidavit filed by Renate Raeber, former head of business management of UBS Bahamas, said: “As it relates to Schedule 1 of Exhibit RR-5, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, UBS has produced all of the contract notes, trade advices and trade receipts in its possession. UBS does not have any other contract notes in its possession, other than what has already been produced.”

Irina Tsareva claimed, “This proves our worst fears. UBS likely never executed a single trade on NYSE or Nasdaq.” The couple asked for the documents mentioned in the affidavit. UBS, advised by lawyers, refused repeated demands for the confirmations.

According to the New York lawyer who was cited earlier, “Confirms are always provided, they show up in trading account under statements, at least in all the retail trading platforms I’m aware of (E-Trade, Schwab, Fidelity, TD, etc.). It’s not because trade confirms aren’t provided due to bad customer service, but rather, here, that they weren’t provided, because UBS didn’t execute some of their trades that were allegedly submitted by email.” He would allow his name to be used. Many lawyers and law professors contacted on this story declined to comment. It is common for lawyers to avoid criticizing prospective major clients.

The Court

The judge on the case, Ian Winder, had ordered that each party must file two witnesses and two experts. Raeber, in an August 1, 2019 affidavit, swore that the UBS had no witnesses and that the Starostenkos had not filed expert witness statements. This last was not true. The Starostenkos had filed four in April and May.

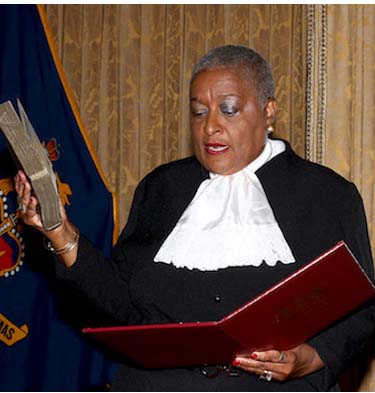

Raeber said that UBS needed six weeks to get its own witnesses. Nevertheless, when, more than six weeks later, the Starostenkos arrived for the first day of the trial September 23, 2019, they heard that it was just a “housekeeping hearing.” Judge Ruth Bowe-Darville, a new judge on the case, had been sworn in May 2019 just three days before she reached retirement age. There was widespread criticism of that appointment, questioning the independence of the Judicial and Legal Services Commission. Yet, the prime minister would extend her tenure for more than two years, enough to keep her on the UBS case.

Irina Tsareva said, “We came to the September 2019 trial, and it was cancelled.” Judge Bowe-Darville had accepted UBS’ motion that it had no witness and needed to postpone the trial. She set no future date. Raising the corruption issue, a Bahamas critic wrote, “Legal observers have opined that she [Bowe-Darville] was one of the most political judges on the bench as the FNM appointed party supporters in an attempt to secure convictions in the prosecution of political opponents.” She never released a ruling, an order or even transcripts in the Starostenkos’ case.

Corruption or not, UBS benefitted from Bahamas judges’ failure over years to hold a trial. The bank showed an interest in destroying the Starostenkos’ ability to bring the case to court.

For four years, Bowe-Darville and her successor allowed the bank’s motions to block a trial and squeeze the Starostenkos, who by then said they had no income or savings. Irina Tsareva wondered “why have all of UBS’ applications been heard even if they are clearly absurd, and ours are pending for literally years?”

The years of repeated filings-to-delay, led Chief Justice Winder in May 2023 to rule that “there is no doubt that there was inexcusable delay in the matter…on the brink of a trial date.” He said “The delay caused thereby has deprived the Plaintiffs of a trial date.” Since March 2023, it was required to fix a trial date six weeks after the defense was filed. Irina Tsareva said, “After such a ruling the course of action would have to go straight towards the judgment against UBS.”

Seizing the house

But the new case judge Carla Card-Stubbs, in office just three months (since February 2023), didn’t order a trial. Instead, in July, she said that UBS’ application to sell the Starostenkos’ house would be heard on December 8 and that the Starostenkos’ application to take back the home and to enjoin UBS from further applications for sale would be heard on December 11. This seemed time-line backwards. Meanwhile, in September, UBS filed an an affidavit by George Damianos, owner of Sotheby’s Bahamas, appraising the Starostenkos’ home at $1 million. He was not a certified appraiser in the Bahamas, not listed in either of the appraiser databases. See this and this. Evaluations of $3.4 and $3.7 million had been made by legitimate appraisers.

Then on December 11 2023, Carla-Stubbs ordered that their applications opposing the sale of their home would not be heard until April 22 and 29, 2024. Not till June 24, 2024 would the Starostenkos be given a date for a hearing on their other applications. The dates were backwards. And the Starostenkos, after ten years, were still denied the right to a trial, violating the court rules. It was more evidence for the Starostenkos that the fix was in.

The court

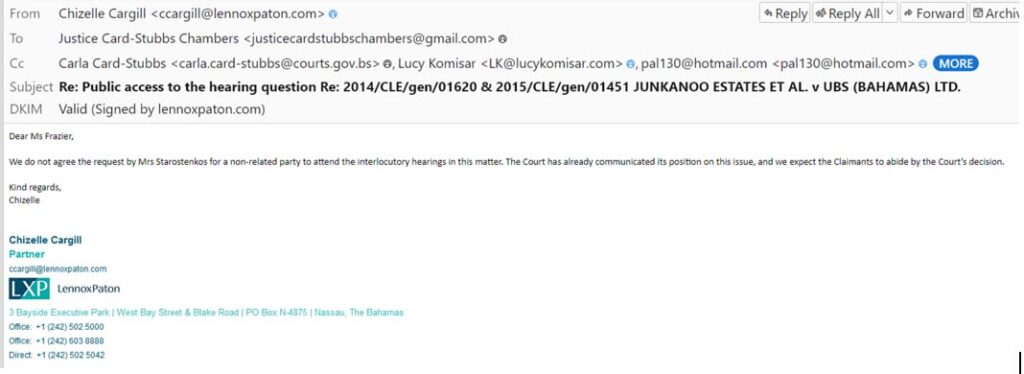

I viewed the February 20, 2024 court hearing on a zoom call. I had watched several other hearings until, apparently on a question from the UBS lawyers, I was identified as a journalist. During the July 14, 2023 hearing, Judge Card-Stubbs had ordered me off the zoomcast and said I could not attend the December 8 and 11 hearings, because they were on “preliminary” issues, but I could attend the “main” hearing, which would be the trial, something judges’ rulings supporting UBS motions have for a decade successfully prevented. I tried again in February, but was ordered off.

The Starostenkos protested Card-Stubbs’ refusal to set a trial date, her order throwing this reporter out of the zoom public court room, and her failure to order a hearing on evidence of the possibly fraudulent appraisal of the Starostenkos’ home. The judge refused permission to present the issues to the Court of Appeal. She seemed less interested in a trial on the evidence of UBS’s fictitious trades than the disposition of the Starostenkos’ property.

She did not recuse herself over consideration of UBS’ attempts to sell the Lyford Cay house or reveal in the hearings that she is a real estate agent.

The judge ran a hearing April 22 on the Starostenkos’ attempt to repossess their home and block UBS’ attempt sell it on grounds the eviction was illegal. This time this reporter didn’t get on the zoom connection long enough to be knocked off. Here I was (top right) ready to view the hearing. Then the zoom meeting curiously was ended before it began.

When I attempted log in again, I was not admitted. “We’ve let them know you’re here” remained on the screen for nearly three hours, indicating that the judge did not want an American reporter looking into the case.

The Starostenkos expressed their “concern” to the court about the ban, noting that Justice Brian Moree – later chief justice — in a 2002 judgment declared, “The Courts at every level are fully free open and public forums which operate with open doors through which the media (including the International News Media) and representatives of public, civic and non-governmental organizations may enter without hindrance. The proceedings of our Courts may be freely and fully reported.” The Starostenkos said, “We hope the other side would also agree to Ms. Komisar attending the hearing.”

But UBS said it does not want this journalist at the hearings.

I was blocked again the following week as Judge Card-Stubbs violated the Bahamas courts’ commitment to allow the public and press at hearings.

The U.S. courts

If the right to a legal challenge against a global financial company is problematic in the Bahamas, there are the U.S. courts. The Starostenkos in November 2019 had filed a case in U.S. Federal Court, Southern District of New York, which has authority over violations of SEC regulations. They sued UBS for creating 51 false trade records. UBS lawyer John Murphy curiously argued that if, as the Starostenkos claimed, there were no real trades through the U.S. — which he neither confirmed nor denied — then U.S. courts had no jurisdiction in the case.

U.S. federal judge Katherine Polk Failla and the appeals court dismissed the case without allowing discovery on grounds jurisdiction belonged in the Bahamas, not the U.S. (Failla’s former law firm, Morgan Lewis & Bockius, in 2014 bought Bingham McCutchen, one of the main law firms of UBS in the U.S.) The Starostenkos filed a complaint with the SEC. And in February this year, the couple filed a petition for review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

How does a bank accused of counterfeiting trades simply shrug off the allegations and avoid arguing a defense in court? And why should the SEC and U.S. courts not care? The SEC hasn’t responded to the Starostenkos’ complaint.

UBS officials in U.S.

An early draft of this article was sent to Naureen Hassan, President Americas, UBS, and to Erica Chase, head of media relations, Americas, UBS. Hassan had been first vice president and chief operating officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and was an alternate voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee, powerful positions in the U.S. financial system. She declined to comment.

Instead, I was contacted by Jonathan Humphreys, media relations director, UBS Global Wealth Management Americas. He insisted that our phone conversations and emails be off the record, but that didn’t matter since he didn’t say anything of relevance. He declined to provide a sample UBS confirmation to prove that the ones the Starostenkos got were valid.

The only quotable response, attributed to “a UBS spokesman,” was: “We have provided all relevant documentation as required in this [Bahamas court] case. We believe these allegations have no merit.”

I emailed Humphreys, “If the allegations have no merit ….Tell me what has no merit. Tell me your defenses against them. I would be glad to include that in the story. In fact, I would love to include such defenses in my story. The time to say something has no merit is when you have been given the opportunity to challenge the full text provided to you of everything I plan to write, and you decline to do it.

There was no response.

In a shuffle announced in July that named a new UBS Americas chief, Hassan said she would leave the firm.

UBS in Bahamas court case

Though UBS Bahamas continues in voluntary liquidation, UBS AG, the Zurich conglomerate which owns the Bahamas subsidiary, on January 22, 2024 registered in the Bahamas to provide full banking services. The Starostenkos added it as a defendant in their case. But UBS refused to be served with the legal papers at the Credit Suisse office in the Bahamas. UBS AG did not respond to my query asking why. The Starostenkos in March asked for a court judgment on UBS’s failure to acknowledge service. No response from Carla-Stubbs.

A May 8th hearing before the Court of Appeal, which included the Starostenkos’ request for a ruling affirming that court hearings are open to the public and journalists, was opened and closed in 10 minutes, postponed to June 20th. They were trying to get the Court of Appeal to order Judge Card-Stubbs to follow the law and set a trial date. On June 19th she cancelled the hearing at which she should have set a trial date. The Appeal court hearing was also cancelled.

Then on June 11th, Bahamas Attorney General Ryan Pinder filed an application with the Supreme Court asking for a ruling that the Starostenkos not be allowed to file any legal proceedings without a judge’s approval. (Pinder, with a Bahamian father and American mother, got an MBA and law degree from the University of Miami, then took a six-month course in the Bahamas so he could practice there. He renounced his U.S. citizenship to run for parliament.)

The application is based on an affidavit by Lena Bonaby, an associate of Delaney Partners and a member of the law firm’s team handling the voluntary liquidation of UBS Bahamas. The affidavit said their legal proceedings were “vexatious.” In other words, a UBS lawyer says the Starostenkos’ attempts to get a trial on the merits is “vexatious.” Now, at the end of a decade when judges have repeatedly refused to order a trial, one can’t see the “discovery” or arguments on both sides. But the attorney general, a political appointee attempting to block the Starostenkos from using the court system at all, shows the lack of access to legal process in the Bahamas for anyone challenging a powerful institution such as UBS.

Who was right, who was wrong? The Starotenkos made the trades. UBS refused to provide confirmations of the trades. That doesn’t mean they were not made, but it raises questions. Why no confirms? The Starostenkos dropped below the amount required to be held in the loan trading account. They did not top it up from their cash account. UBS did not work out an arrangement with a customer who had traded hundreds of thousands of dollars and had legitimate complaints of how the trades were handled. It seized a house worth many times the breached limit. That may be legal. The court fight has gone on for more than ten years. Allowed in the Bahamas. If this is David vs Goliath, Goliath has so far won. A message to prospective UBS clients.

Changes have been made to the article originally posted to reflect new information.

Pingback: 10 August 2024 – Breaking news: UBS’ fraud exposed – Securities Fraud Bahamas: banks UBS, Credit Suisse