I spent six days in August at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world‘s largest arts festival. Out of the hundreds of plays presented, I sought out those about politics. I‘ve divided the best by their themes. Here are several about war and its fallout: Angel, Glasgow Girls and Hess.

“Angel”

Written by Henry Naylor; directed by Michael Cabot.

“Angel” is the stunning final play in Henry Naylor‘s trilogy about the west‘s imperial wars. The first, which I saw in Edinburgh in 2014, was The Collector, inspired, by the U.S. prison at Abu Graib. not just about American brutality against Muslim prisoners, but about America‘s flouting of its moral commitment to people who believed its stated values and risked their lives to help the American project.

The second, “Echoes,” a 2015 Fringe play I saw at 59E59 theaters, explores the imperialist mindset as it compares the experiences of two women who lived 175 years apart in Ipswich, England, and were each swept up in the murderous rampage of godly imperialist killers.

In “Angel,” Filipa Bragan§a, who starred in “Echoes,” gives a tour de force performance as Rehana, a real person who lived in Kobane, a Kurdish town in northern Syria. She was known as the Angel of Kobane because she took up arms to fight ISIS and is said to have killed 100 ISIS fighters. Her father had taught her to shoot to protect their farm, practicing on orangina cans.

Bragan§a, an exceptional actress, captures the accents of multiple characters. The play is directed with careful intensity by Michael Cabot.

Rehana is the child of farmers. She wants to go to law school. She sings Beyoncé‘s “All the single ladies.” But in 2014, her family must flee, because “Daesh are coming.” “Don‘t worry,” she is told. “They will look after us in Europe.” But the Turks won‘t let them cross the border, a kilometer to the north. And her father stays to fight.

The drama begins when she gives up safety to return to find him. Tension rises as Bragan§a acts out the horrors that ensue. Her driver Sabah is killed by Kurds, because he has tattoos and is believed to be Ayzadi. Then she is captured, shackled to other women, selected for rape by a man of influence. She escapes by pretending to have her period.

A pacifist, she becomes part of a fighting unit of women whose choice is “violence which empowers you or that enslaves you.” She teaches recruits how to clean guns, to load and shoot at orangina tins. At her abandoned home, she finds her legal textbooks charred, used as fuel. Sweet, innocent, she becomes tough and battle hardened. Even in tragedy, we are uplifted by the unusual courage this “Angel” displays.

Naylor‘s play won a 2016 The Scotsman Fringe First Award.

Glasgow Girls

Book by David Greig; conceived for the stage and directed by Cora Bissett.

Refugees should be the lucky ones if they get asylum. But a tough, vibrant musical about another real story, a deportation threat to a young Roma, has been a hit in the UK and at the Fringe.

In 1999, British authorities moved asylum seekers from London to Glasgow. Aggie had been threatened with death and the family home was burned down in Kosovo, where both sides in the conflict opposed the Roma. She was put in school in Glasgow, and then in 2005 her world collapsed when the Home Office announced she would be deported. The government view was, “I think they‘re over here to live for free.” But ironically, people also accused asylum seekers of taking jobs.

Her classmates unite to get Aggie back from deportation detention. They organize letters to embarrass the Home Office. They get support from members of parliament to stop the detention and removal of children. They arrange for lawyers to speak at the United Nations. When asylum seekers in the area begin disappearing at night, they go on patrol, and when vans come, they call the targets: “Tonight!”

And then they write a show about the campaign, “Glasgow Girls.” There‘s a Broadway sound to this jazzy pop musical, with a mood reminiscent of “West Side Story,” though it sometimes is hard for a foreigner to understand the Scottish dialect. The direction is also Broadway style, even a dance with umbrellas for a tongue-in-cheek number about what they love about Glasgow: “It‘s constantly raining.” A young violinist perched above the stage reminded me of “Fiddler on the Roof.”

The young women have talent – and panache. It‘s a powerful political musical about how solidarity makes people winners.

“Hess”

Written by Michael Burrell; directed by Kim Kinnie.

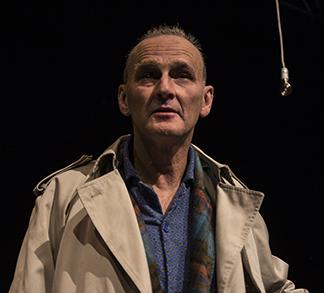

Then there is the detritus of war, what‘s left behind. Michael Burrell‘s unusual fictional story deals with the case of Rudolf Hess (portrayed by the excellent Derek Crawford Munn), who was Hitler‘s deputy. In 1941, he flew solo to the UK and bailed out over Scotland on a peace mission to end the war. The idea, bizarre on the face, was to make a deal where Germany would be supreme in Europe and the British Empire in the rest of the world.

Instead, he was captured, condemned at Nuremberg not to death but to life in prison. To a prison that would hold only him in Spandau in the west of Berlin. This play occurs during his 40th year in confinement and was first staged in the late 1970s. He died in 1987.

Supposedly, he has evaded prison guards on his way to a military hospital, and in this space, he sees people, the first since his confinement in Spandau in 1947. We hear what he says to that audience about himself, about the Third Reich and current times. With deep set eyes and graying hair combed to both sides, Munn is at various times in a light tan-plaid raincoat or green bathrobe and slippers. Sometimes he feeds the birds. His voice is chirpy, but occasionally explodes into fury.

He declares that he had solutions, a dream. And he notes that the Russians were “your enemy, too.” The Germans and the West should have joined to smash them. He says Churchill was too weak, afraid of his American allies. He adds, “You too have dealt with the military on your hands.” He doesn‘t explain the weird plan he wanted to propose. He calls himself “The most expensive prisoner in the world.” And he declares, “They are afraid to let me out.” He twists on the floor in anguish at history and his body, now wracked with an ulcer.

But Hess never stopped being a National Socialist. At his 9-month trial in Nuremberg, where he saw the old files of Goering and von Ribbentrop, he said he didn‘t know of the camps. And he has no regrets; he would have wanted a new Reich. Still, he protests, “How can I be tried by Americans and Russians. I was out of the war before they got into it.” He was acquitted of crimes against humanity but convicted of crimes against peace. He protests that “all war is a crime.”

He sounds like a lawyer arguing for acquittal. And not very credibly. Some prominent politicians tried to get his release – the post-war German government got other Nazis out – but the Soviet Union refused. The play is a fascinating imaginary footnote to history.

Pingback: 9.09.2016 Nearly Naked Links | Daily Links & News