By Lucy Komisar

August 3, 2009

Corazon Aquino, who died on July 31st, is an historic figure who played the role scripted for her by her late husband, Benigno Aquino, to end a dictatorship, but missed the chance to usher in real democracy.

Benigno, an opposition leader, had been murdered in 1983 on the orders of dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

In January 1986, I went to the Philippines to chronicle the growing movement against the Marcos dictatorship. I was there for the February people power revolution, a non-violent massive street protest of which Cory became the titular head and which finally drove Marcos from power.

In January 1986, I went to the Philippines to chronicle the growing movement against the Marcos dictatorship. I was there for the February people power revolution, a non-violent massive street protest of which Cory became the titular head and which finally drove Marcos from power.

I remember being outside the presidential palace the night he fled and racing through the streets when gunfire erupted.

The U.S., which had supported him for decades, flew him and his wife Imelda to Honolulu, along with documents that detailed how they had looted the country and where the money was. Think Switzerland and Liechtenstein. See Marcos’ Missing Millions.

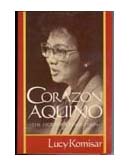

I returned months later to research and write a political biography of Aquino (Corazon Aquino: the Story of a Revolution, Braziller, New York, 1987, also published in the Philippines and in Switzerland).

The question everyone posed then was whether President Cory Aquino, of a family of sugar oligarchs, would betray her class, institute land reform and usher in real democratic reform. The answer, alas, was no.

Her brother Jose Cojuangco was corrupt and used his connections accordingly. She didn’t have the vision or fortitude to challenge him and his ilk and make the political break that was needed. The Philippines today doesn’t have a strong-man dictatorship, but it has a corrupt oligarchic rule, run now by Gloria Macapagal-Arroyao, the daughter of late former Philippine President Diosdada Mcapagal.

Cory Aquino missed her chance.