By Lucy Komisar

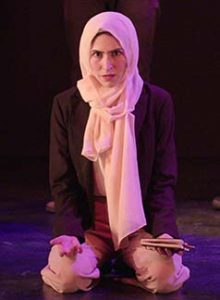

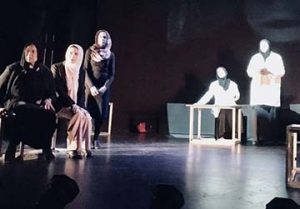

This stunning play, sometimes surreal, tells the story of Basra, Iraq, in 2007, from the point of view of the people who lived there, the residents and the militias. The main character, Hero (Karen Alvarado, who also directs), is a woman in search of her disappeared husband, Aqeel (Sufi Malhotra), who was a translator for the British. As counterpoint are militiamen who comment on events in an almost comic fashion.

This was a period of exceptional violence, if that phrase even has meaning, after the British withdrawal from Basra, southern Iraq. Playwright John Meyer had been in Iraq that year as a US Airborne Ranger. The play was built on a collaboration with artists from Basra.

Hero was 10 when the Americans invaded Iraq in 1991; when the play occurs in 2003, she is 23.

A British radio broadcast is suddenly heard over a hand-cranked radio. Hero is being interviewed by the BBC.

Militiamen are listening. They talk about how Americans view the war through movies and joke about how they will be depicted. In 1993, ‘Hot Shots,’ Charlie Sheen …he kills Saddam twice, first in a sword duel, and then Saddam comes back but he’s like werewolf Saddam. Well, it’s a comedy, so they push a piano on top of Saddam and kill him. It was 1993, but Saddam died in 2006. The piano must have missed.

The laconic BBC reporters appear half bored by the repetition of violence.

A militia man says, “But what if it was our story to make?” If they made own movie, “Like, it’s first-world status thing. Does your country make bombs? Yes. Does your country make movies? Yes. Congratulations, you are now a first-world power. We could hire Oliver Reed or…”

Hero says Saddam Hussein hated Basra, the city I was born in. He used to say, ‘Basra is the bride of the Gulf, but she’s a peasant. Peasant brides deserve three days of nice treatment, and then chase them to the fields.’

Hero says, “The story I am trying to tell you this time begins in 2007. When the British military abandoned my city, Basra, to the militias.” She adds, “Despite the violence of this period, we are not all dead.”

The story moves between Hero‘s story and the militiamen. There are problems in her marriage, because she hasn‘t had a child and worries her husband will leave her. Her mother-in-law, Monica Vilela (Um Aqeel = Mother of Aqeel), says, “Your body punishes you for reading too many books.”

On stage you see bodies of the dead, burned and bloody. Then everyone gets up and cleans off the blood and filth. A woman studies law. A man goes shopping. But mortars are launched and crash, destroying one house, damaging others.

When the British left, the militias imposed ruthless Islamic law. We see them confront several young Iraqi women in modern dress and hold them at gunpoint. The women go down on their knees, hands up. The militia soldiers gun down the young people and drag them off stage. Hero resumes her ‘dead’ posture.

A British journalist in a spot of light: “It seems so very long ago. On April 6, 2003, the British Army occupied the city of Basra, Iraq, and a sense of excitement hung in the air.”

Now back up in time. Aqeel is angry Hero talked to the British. Militiamen have been following him and tracked him to his home. Sometime after, he disappears.

But the truth is more complex. Hero says to her mother-in-law, “You made Alex work for the British, we must go to the morgue.” Aqeel appears on a slide. Hero scratches name into the concrete tombstone with a rock shard.

Two months later, she receives a letter addressed to Aqeel, stating that his application for a visa had been denied. She suspects he took his pay and left

This is a compelling play by a very young man, poetic, sensitive, politically astute. It tells history, attitudes and feelings. The actors are an ensemble who inhabit their roles as if they were the characters. And the ghosts of characters. In fact, I was surprised to learn they were not all from the region.

“Bride of the Gulf” was staged three times at the New York Theater Festival, Feb-March 2018. It deserves a production by a serious Off-Broadway theater.

“Bride of the Gulf.” Written by John M. Meyer; directed by Karen Alvarado; music by Sean Ullmer and Kais Ouda. Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Edinburgh. Aug 2 – 27, 2018.