By Lucy Komisar

Robert Icke’s “Oresteia” is a brilliant takes-your-breath-away modern version of the Greek narrative of Athens’ war on Troy which, at its center, is about male warmongering and sexism. It makes you realize that little is new about rulers who would sacrifice their own children as well as masses of citizen subjects to maintain their power over other lands. The universality is made clear when Calchas (Michael Aabubakar), a Greek god and seer, intones names of god Zeus, and then goes on to name two dozen others, Allah, Apollo, Buddah…, because military in every land called up gods to bless their marauding.

Icke pulls together stories from several Greek plays on the narrative and turns them into a near cinematic political thriller and a moral condemnation of macho politicians and world leaders.

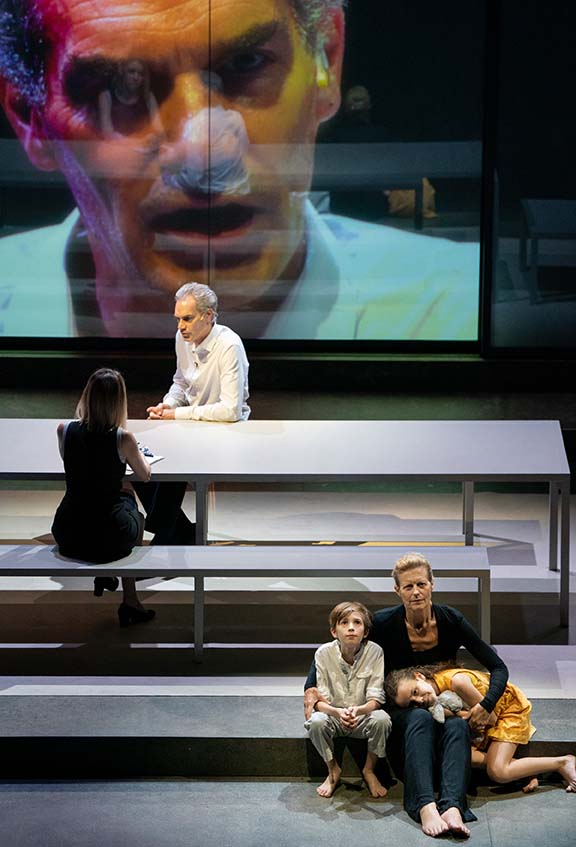

We see Agamemnon (the powerful, moving Angus Wright), on a large screen, declare, “It’s essential to ask the bigger questions. Why are we doing this?” An interviewer gets more concrete: “Do you study other conflicts?” He replies, “I try and look forward rather than backward.” Nothing like not learning from history.

Now we get an amazing conversation on the morality of killing for your cause, which could take place in a Pentagon war room, so it is worth citing in detail. Transfer to U.S. wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Ukraine. All done almost casually, as Agamemnon wears a white shirt and black pants and is barefoot, no suit and tie.

The problem is that Athens’ fleet, which must sail to attack Troy, is becalmed. The gods say he has to kill his daughter to get the winds. Agamemnon declares, “I’m not a pacifist.” There appears a text, “child killer.” That represents all the citizens who will perish, though leaders prefer “not pacifist” to “killer.”

His collaborators appear. One says, “The enemy is mobilizing. – a huge movement of troops into positions which suggest we are extremely close to an attack.

Agamemnon: “So we need to strike first.”

His brother Menelaus, (Peter Wight, in a dark suit, good as the typical state bureaucrat): “Yes.” He wants the war to avenge Paris of Troy’s kidnapping his wife, Helen.

Agamemnon: “We run the better part of the world. Great men have sat in your chairs. Honor their memories.” Shivers go through you when you realize he is speaking the words of decades of U.S. foreign policy makers who assert that their country is the hegemon and that war to preserve that power is noble.

Menelaus has no problem with killing his niece. He says, “You would be putting this country before your family in real terms. You’d hold their kids up higher than your own, and – if that got out, you would be – idolized.” So modern in thought and language!

He throws on the table photos of dead soldiers. Another says, “If it was ended…no more deaths.” Except, before it ends, a lot more deaths.

Agamemnon: “She’s not made that choice, she’s not a soldier.” She represents all the innocents the country’s leaders send to their death. To cut guilt, they tell him she wouldn’t feel anything. A single tablet with active ingredients sodium pentobarbital at 75mg and phenytoin sodium at 30mg. This tablet has a particularly bitter taste, so a sweet drink is normally offered thereafter for comfort. Sleep would follow, then unconsciousness.” The rationale of executioners.

He says, “I should resign. No: the life I should take is my own.” Of course, he won’t. With no sense of irony in his description of murder, Menelaus declares, “It’s a civilized procedure.”

Agamemnon puts himself in a long tradition. He says, “I worshipped them when I was young – the generals, their ranks, their battles, their medals, you know? They moved the borders of the world.” Moving borders was called conquest then, imperialism now.

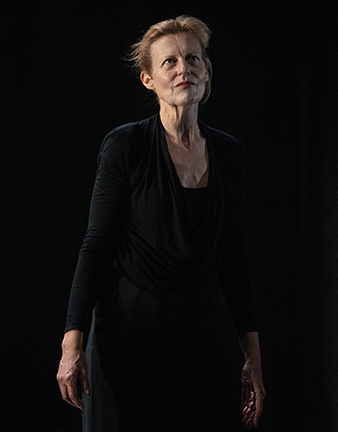

The only honest person is his wife, Klytemnestra (the superb Anastasia Hill, svelte in a black pants suit, her blonde hair pulled back, suddenly a real human being): “The world in which you have to kill your child? You get down on your knees every night and you pray – but let’s call god by his real name, call him the way we actually live our lives, the things you actually serve – call him money, call him power, call him wars against the weak – “

Agamemnon: “I’m trying to be honest and you know this war is a necessary evil, we are fighting an enemy that can’t be left unfought.”

Klytemnestra: “Put whatever words on it you like but it’s killing people in order to take their things or prove them wrong or ‘cause you don’t like the people they are – but let’s be clear, those people die.” This is a stunning indictment of the U.S./NATO attack on countries that don’t accept their rule.

The killing is totally modern. He holds his daughter in his lap and says (still no irony), “You’re a very brave girl.” Behind a screen are witnesses. Once it’s done, papers fly across the stage to show the fair winds have come. Years later, triumphal martial music heralds the Athenians’ victory.

A clever interlude is a TV interview of Klytemnestra, with the interviewer a stand-in for all the fools you see on TV. He says, “Your husband left only days after the tragic passing of your daughter, of Iphigenia. She corrects his pronunciation, “Iphigeni-a. Yes.” He asks if her husband might feel responsible for those who died. She doesn’t know. She hasn’t seen him. Interviewer: “But as a woman, you must have an opinion? These are people’s children.”

Her riposte: ‘As a woman’. I find that a disquieting phrase. I mean, I don’t have sets of opinions depending on the mask I’m wearing, it’s not as if I think one thing when I’m – breastfeeding and then change entirely when I’m doing something – I mean, I can’t answer you as a woman. …My gender isn’t something I selected for myself; it doesn’t surprise me when I look in the mirror.”

He asks: “Finally, what does today mean?” She is out of patience: “Who wrote your questions? Well, it means something different to each of us.”

After Agamemnon arrives home, the two go to a balcony to address the crowd. Klytemnestra says, “We are all, every one of us, all your families. Around the world. We stretch our hands out to hold yours. We share your loss. We mourn your loss.” She is an excellent orator. Agamemnon is annoyed, suggests her speech went on too long, then declares, “We won, we got them!” More and more, we sympathize with Klytemnestra and think Agamemnon a macho fool. Though he notes his brother Menelaus didn’t come back.

He has brought back a young woman, Cassandra (Hara Yannas) who wears a dress the same saffron color as Iphigenia’s. There is suspicion she is his personal conquest. She is also a soothsayer. She declares, “the house breathes slaughter. He dies. Murder. He dies now. No good gods here. Not in this story. These are his final moments.” Cassandra cries loudly, like a wounded animal. Then, “It’s same story doesn’t stop doesn’t cease my story is your story is – family extinct – only survivor —father after father the blood runs down.”

Agamemnon goes to the large concrete tub to take a bath.

Klytemnestra goes to the bath with a sheet she will throw over Agamemnon before she stabs him. She says, “The war came home,” that killing him is just “the balance” of his act.” Indeed.

The rest of the play belongs to the high-strung Orestes (a fine Luke Treadaway) who had left the city, is distraught and being treated by a doctor. The music is Nick Lowe’s pop “The beast in me/ Is caged by frail and fragile bars/ Restless by day And by night rants and rages at the stars,” about a struggle with destructive habits and personality traits, first recorded by Johnny Cash, Lowe’s father-in-law.

The rest is told according to the Greek narrative. Orestes puts on his father’s red robe and kills Aegisthus (Wright) who has become his mother’s lover. Of course, Klytemnestra will be his next victim, placed in a pool of red wine signifying blood on the dining table where they had imbibed wine at family dinners.

Most fascinating is Orestes’ murder trial with the goddess Athene (Yannas), as judge. Prosecutors and defense are at opposite tables. The names of exhibits are lit on a screen. Again, Icke’s feminism is powerful. Klytemnestra, now a prosecutor, declares, “A sister, a father, a mother – are dead. There has to come an end. But allow me to ask the house: why does the murder of the mother count for less than that of the father? Because the woman is less important. Why is the mother’s motive for revenge lesser than the son’s? She revenged a daughter; he a father. Because the woman is less important. This woman has paid the price. But this house cannot be a place where the woman is less important.”

A stunning feminist anti-war take on the Greek tragedies.

”Oresteia.” After Aeschylus, adapted and directed by Robert Icke. Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue between 66th and 67th Streets, NYC. Tkts (212) 933-5812. so*******@**********rk.org Runtime 3hrs30. Opened July 26, closes Aug 13, 2022. Review on New York Theatre Wire.