By Lucy Komisar

The reenactment of the 1965 Cambridge University debate between James Baldwin and William Buckley is an interesting if minor moment in civil rights history, but a disappointment as theater. That is partly because two long monologues (not really a debate) and two short introducers don’t provide enough dramatic tension for theater. You want a real interaction. And partly because two of the actors are fine but the other two are middling to mediocre.

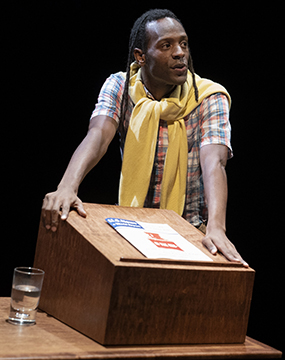

The play begins with two students introducing the men they support. Gavin Price, a white actor as Heycock, speaking for Baldwin, sleepwalks through his role, a classic case of mailing in his lines. On the other hand, Christopher-Rashee Stevenson, a black actor playing Burford, favoring Buckley, is superb. His entrance was an explosion, packing surprise and drama into every line. He is an actor of importance, till now working with groups such as Mabou Mines. Maybe almost wasted here, he should be “discovered.”

The problem is the main event. The civil rights explosions of the early Sixties, including the arrests of Martin Luther King Jr. and violence in Alabama, were drawing the world’s attention to the repression of the country’s blacks.

At Cambridge University in England, novelist and essayist Baldwin (Greig Sargeant) and conservative writer and TV host Buckley (Ben Jaslosa Williams) are debating whether “the American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” This review doesn’t consider the texts as the author’s script: those are given.

Of course, Baldwin is right in detailing the horrors visited on American blacks, then called Negroes. (Negro to black to African-American, etc, made a lot of people feel good but changed nobody’s lives.) Baldwin has a dark wit: “It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you!”

Or that, “It is only since the Second World War that there’s been a counter image in the world, and that image had not come about through any legislation on the part of any American government, but through the fact that Africa was suddenly on the stage of the world and Africans had to be dealt with in a way they had never been dealt with before. This gave an American Negro, for the first time, a sense of himself beyond a savage or a clown. It has created, and will create, a great many conundrums.”

Buckley is a supercilious racist arguing that American Negroes are better off than their comparables in other countries. “But we must also reach through to the Negro people and tell them that their best chances are in a mobile society. And the most mobile society in the world today, my friends, is the United States of America.” Of course, that is provably untrue, with much more mobility in Europe, especially Scandinavia, than in the U.S. And he says Negroes’ problems are their own fault for not struggling hard enough.

Buckley warns “that where the Negro is concerned, the danger as far as I can see at this moment is that they will seek to reach for some sort of radical solutions on the basis of which the true problem is obscured.” In fact, most of the “radical solutions” have been symbolic, lately pulling down statues rather than organizing all workers around their interests.

Greig Sargeant conceived the play with the Elevator Repair Service company. So he took the role of Baldwin. Director John Collins obviously didn’t have the option of casting someone else. But Sargeant never persuades you he is Baldwin. Even visually, he doesn’t call up the man. Many people have seen Baldwin on television. He was an elegant, sophisticated, subtle, bitingly clever man. None of that comes through.

Sargeant’s Baldwin is plodding. He reminded me of late Congressman John Lewis. In fact, he’d be a good choice for a Lewis biodrama. Occasionally he raises his voice to anger. Mostly, he speaks softly, without passion. And mostly, he stays at his podium, sometimes turning to see audience members to his back.

Ben Jaslosa Williams is the incarnation of Buckley, tall, lanky, with a chiseled face, that aquiline nose, and even, for a few minutes, the low rumbling voice that was Buckley’s trademark. You think he did it to show you he could. He walks around engaging the audience. His arguments are facile: should we tear up the works of Plato and Aristotle because they supported slaves?

A minor complaint: I don’t know if there’s a recording of the Cambridge event and if Williams’ mispronunciation is deliberate, but Williams calls civil rights leader Bayard Rustin BAYard instead of BYEard. A smart actor or director would know better. (I was a student volunteer at Rustin’s 125th Street Harlem office of The Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South in the early 60s. I know how to say his name!)

In the end, the vote of the Cambridge students was 544 for the proposition and 164 against.

Sargeant has added an invented bit co-written with April Matthis based on his communications with playwright Lorraine Hansberry (Daphne Gaines). Most of it is how they met in 2007 when hired as actors in a production of Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury,” because there hadn’t been any blacks in it. A stretch to talking about the persistence of racism with a bit of self-promotion.

The debate makes a good reading for students. But this is a disappointing theater production.

“Baldwin and Buckley at Cambridge.” Conceived by Greig Sargeant with Elevator Repair Service (ERS). Directed by ERS Artistic Director John Collins. The Public Theatre, 425 Lafayette Street (at Astor Place), NYC. Runtime 60min. Opened Oct 2, 2022, closes Oct 23, 2022. Masks not required at most performances (check website). Review on NY Theatre Wire.