By Lucy Komisar

RALEIGH, North Carolina, Inter Press Service (IPS), April 27, 2010

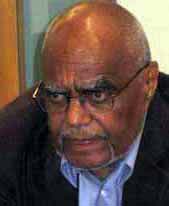

Robert Moses, 75, a legendary leader and organiser in the 1960s U.S. civil rights movement, was huddled with a dozen people discussing plans for a campaign to make quality education a constitutional right. On one side was his son Omowale, 38. Next to Omo was John Doar, 89, head of the civil rights division of the U.S. Justice Department in 1960-67 and prosecutor of the major civil rights cases of that era.

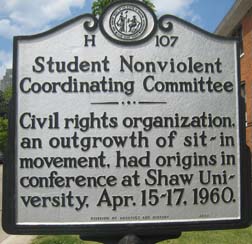

The age differences were noticeable at the conference they attended this month in Raleigh, North Carolina, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It was a moment for the elders – as high school and college students at the conference called them – to pass the torch to a new generation of activists.

SNCC, or snick, as it was known, was founded on the campus of a black college, Shaw University in Raleigh, to coordinate the Southern student civil rights movement. A few months earlier, four black students had sat-in and demanded service at a lunch counter at a Greensboro, NC Woolworth’s department store that reserved stools for whites. The management refused.

On succeeding days, more students joined them. As word spread, other college students staged sit-ins around the South.

SNCC took the movement further, evolving from a coordinating committee to an office that sent field secretaries to most Southern states. By 1963, there were 181 young staff and volunteers who lived and worked with local leaders to register and educate black voters and wage economic campaigns to gain their rights.

The next year, 1,000 young people, mostly whites, came to Mississippi for a SNCC campaign to register voters and run 28 political freedom schools. Two of the whites and a Southern black youth were murdered by racists.

In 1964, SNCC organised a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party challenge to the all-white state delegation to the Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City. In 1965, it challenged the seating of Mississippi’s congressional delegation in Washington. It supported black candidates for Congress and local office; black elected officials in the southern states increased from 72 in 1965 to 388 in 1968.

SNCC actions led to a ban on segregated Democratic Party organisations and ultimately prompted Southern racists to quit and join the Republican Party. The awareness SNCC created played a role in Congressional passage of the anti-segregation Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

SNCC made foreign policy issues part of the black agenda. Staffer Julian Bond won election to the Georgia legislature in 1965, but the body refused to seat him because he endorsed SNCC’s criticism of the U.S. war in Vietnam. A year later, his admission was ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court. He served for 20 years.

Bond told the conference that, What began 50 years ago is not history. It was a part of a mighty movement that started many years ago and that continues to this day – ordinary women and men proving they can perform extraordinary tasks in the pursuit of freedom.

That resonated with the young people. Abeni Nazer, 18, a freshman at the University of Baltimore, said, I’ve never met Dr. [Martin Luther] King, I’ve never met Malcolm X [a Black Muslim leader assassinated in 1965]. But Bob Moses and a lot of people here, I actually get to meet them and I feel like, when you have first-hand experience and you’re sitting face to face with these people, it’s totally different than reading it in a book or seeing it on television. It inspires me more; it puts the passion back.

Robert Moses is a bridge to the modern movement. A former high school math teacher, in 1982, he started the Algebra Project, to develop methods to teach math to low income and minority students. That led to the Young People’s Project, headed by his son Omowale, which trains high school and college students to work with students on math and to promote reform of math education. They follow SNCC’s strategy.

Albert Sykes, 26, a Jackson, Mississippi YPP leader told IPS that SNCC’s lesson was start local and think local. He explained, The initial sit-in was four guys sitting at a lunch counter. It was a single action but had a ripple effect. The message from the elders is to stay local and do small incremental steps, which for YPP is quality education as a constitutional right.

Later, addressing conference participants in Shaw’s gymnasium, he said, We transition from Feb. 1, 1960 and the sit-in movement to the ‘stand up’ movement. Young people in Jackson, Mississippi have to stand up, young people from Chicago, Illinois, from Minnesota, Georgia, have to stand up… And the young people stood up to applause from the elders.

He complained that, Some of the challenges come from the torch not being properly passed between the SNCC generation and our parents and our parents’ generation not handing the work to us.

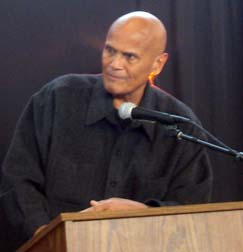

Other SNCC leaders also seek to pass the torch. Ivanhoe Donaldson, who organised for SNCC in Mississippi and Selma, Alabama and Bernard Lafayette, who worked on a Selma voting rights campaign, joined singer and civil rights supporter Harry Belafonte in 2005 to found The Gathering for Justice.

Carmen Perez, 33, a worker for the group, said for her the challenge was a criminal justice system that incarcerates children.

Javier Maisonet, 25, who works in Chicago for YPP, said the sit-ins put everything in perspective. He explained that one SNCC activist said, Once you come to terms with the worst thing that can happen to you, you can do whatever needs to be done.

Lucy Komisar attended the founding conference of SNCC in 1960. She was editor of the Mississippi Free Press, a civil rights newspaper in Jackson, Miss., in 1962-63.

Article on IPS site.