By Lucy Komisar

“In the West you have no idea….” says the opening voice of a man telling of the joys of Russian songs, picking mushrooms in the forests, laughter in the baths…” In other ways, “Patriots,” written by British playwright Peter Morgan and directed by Rubert Goold, on Broadway after a successful run in London, is based on Brits and Americans having “no idea” of the story it tells. It makes it possible for Morgan to mix fact and propaganda, even in a careless moment admitting as much. So, to find out what was true, I relied on the biography “Putin” by Philip Short, former correspondent for the BBC in Moscow, and acknowledged as the most important book dealing with the characters and period of the play.

“Patriots” is what protagonists Vladimir Putin and Boris Berezovsky think of themselves—Russian patriots.

The first voice is that of Boris Berezovsky, one of the “oligarchs” who became billionaires at the fall of the Soviet Union by scamming the system to take over Russian companies. Then we meet Russian president Vladimir Putin.

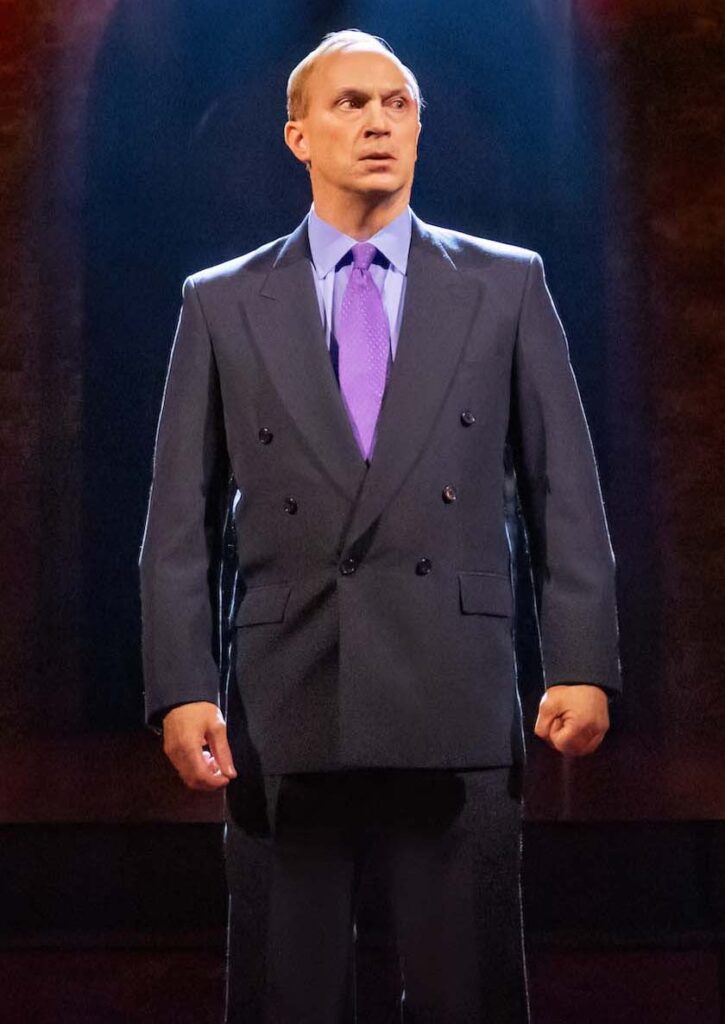

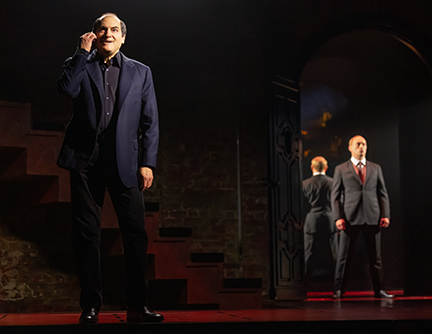

In Morgan’s play, Berezovsky is the mostly (albeit crooked) good guy, set against mostly (albeit incorruptible) bad Vladimir Putin. The problem with black and white is that while Michael Stuhlbarg’s portrayal of Berezovsky is lively, about a complex man who is essentially dishonest, Will Keen’s Putin is flat, since giving him a real personality might humanize him.

In this pas de deux, Berezovsky is the more attentive partner while Putin seems quite comfortable as a solo. And following that metaphor, it is a gorgeous production with Russian singing and dancing. But on substance, it helps to know something of the true events and the cast of characters, what is real and what is fake. So, this review looks at the historical events – what really happened – and the theater script you are invited to believe. Citing Philip Short, some of the script is accurate and some invented. The interactions with Putin are generally invented. I leave someone else to deal with the young oligarch Roman Abramovich and FSB (Federal Security Service, internal security and counterintelligence) agent Aleksander Litvinenko.

Philip Short’s account – if you want to skip the history, go right to The Play below. But you will be flying blind!

So here is Short‘s take on the Putin-Berezovsky story. There was one surprise for me. Near the beginning, Berezovsky calls St Petersburg deputy mayor Putin. He wants an auto dealership. He is told that there is a process, a department in the town hall. “I’m not going to the town hall.” What would he have to do to jump the line? He tells Putin, “I could look after your interest.” Putin says, “I don’t accept bribes.”

Short writes, “When Berezovsky brought a brand-new Zhiguly saloon (auto) to Putin’s dacha, as a token of appreciation for his help (apparently normal government aid) in setting up the dealership, Putin thanked him but refused to accept it. Berezovsky was astonished. ‘He was the first bureaucrat who did not take bribes,’ he told the journalist Masha Gessen years later. Seriously it made a huge impression on me.” Gessen, who has made a name attacking Putin in the western press, does not write about this. Short says, “Most of the people who worked with Putin in St Peterburg have since maintained that he did not take bribes….”

1997 Berezovsky and others wanted to rig an auction for some state media and failed. They campaigned against top officials (First Deputy Prime Ministers Anatoly Chubais and Boris Nemtsov) who had insisted the auction must be fair and got them removed from power. Short says it was a lesson to Putin. “Two of the leading oligarchs, through their wealthy and control of the media, had been able to evict some of the most powerful men in the government and Presidential Administration on essentially specious grounds.”

After Putin became FSB director, in April 1998, five FSB offices working for the Department for Investigating Organized Crime Groups (URPO) reported to FSB official Nikolai Kovalyov that their boss, General Yevgeny Khokholkov, had given them secret orders to assassinate Berezovsky and several other prominent figures. When Kovalyov failed to take action, they made a formal complaint to presidential office and were suspended while military prosecutors investigated.

Berezovsky took the group’s leader Aleksandr Litvinenko to meet Putin and make a full report. Two months later Putin disbanded URPO and transferred Khokholkov to a sinecure in the Tax Inspectorate.

Berezovsky published an open letter claiming FSB was riddled with corrupt officers and demanding Putin act more forcefully to “establish the constitutional order.” That day Litvinenko and his colleagues, some with ski masks to hide faces, gave a press conference repeating the charges. Putin appeared on TV to say there was no independent evidence anyone tried to kill Berezovsky and that the masked officers were under investigation for criminal activities. Litvinenko was dismissed from the FSB and arrested.

On the subject of corruption, Forbes Moscow chief Paul Klebnikov in 1996 wrote that Berezovsky was “a powerful gangland boss.” Klebnikov would be murdered.

Short writes, “Putin had had reservations about Berezovsky ever since their first encounters in St Petersburg. Lyudmila [his wife] told friends that they regarded the oligarch as ‘Enemy Number One’. But curiously after Putin attended Berezovsky wife’s birthday party, something of great importance in Russia, Berezovsky was convinced that Putin was a true and loyal friend. Short: “When Putin was elected, Berezovsky was convinced that his hour had come. ‘Everything’s fine now,’ he exulted. ‘Our man is in power.’” It would become clear Berezovsky had misjudged.

Short writes: “His first mis-step was in April, when he told Putin, even before his inauguration, that he should hold office only for one term. After that, he said, Russia would need a ‘normal President’, elected through a ‘normal party system’. Putin shrugged it off as just another of Berezovsky’s eccentricities, but when the oligarch told Sergei Dorenko, the charismatic chief news anchor on ORT [the TV station Berezovsky controlled] about the conversation, Dorenko was horrified. “You fool!” he told him. ‘You complete fool! You’re not talking to ‘Volodya’ any more. You’re speaking before the throne of the Russian empire! You ought to be on your knees when you go there…You’re an idiot if you don’t understand that…’

“But Berezovsky listened only to himself. Shortly afterwards, he doubled down on his error by opposing Putin’s drive to restore to Moscow the power which Yeltsin had devolved to the regions.” One issue was their refusal to remit locally collected taxes to the federal government. Seven federal districts headed by a presidential representative would ensure that Russian laws were applied throughout the country. Governors would continue to be elected. But they would not be ex officio members of the upper house of parliament which meant they would lose immunity from prosecution. And federal authorities could dismiss them.

Berezovsky opposed the measures because he had won governors’ support in the Duma elections by promising them that Putin would not limit their powers. In open letter in Kommersant, which he owned, he attacked the changes as inappropriate and anti-democratic, which would produce closed, corrupt, monolithic local bureaucracies. Short says he told Putin, “If it’s like that, I shall publicly oppose you,” to which “the president replied drily, ‘as you like. That’s your affair.'” Short writes: “Berezovsky’s mistake had been to think that Putin was his creation and that he could treat him accordingly.”

Berezovsky resigned his seat in the Duma, a post Short says that “he had wangled through money and connections” and tried to set up a party of governors to oppose Putin’s reforms, which he denounced publicly as “a path towards dictatorship.” It never got off the ground. Sometime later, Putin told his aides he would not meet him again.

When the submarine Kursk sank in the Barents Sea in 2000, the result of a fuel explosion, ORT, attacked Putin for his handling of the tragedy – he had been at a beach resort and didn’t provide information fast or accurately enough. But the state had 51% of ORT’s shares. It ended Berezovsky’s control. He insisted on hearing that from Putin, who told him, “The show is over.” They never met again.

The prosecutor general revived a case against Berezovsky for defrauding the Russian airline Aeroflot of tens of millions of dollars through a network of Swiss companies which had creamed off its foreign currency revenue. He moved to the UK and applied for political asylum. He would never return. He sold his ORT shares to Sibneft, the oil company owned by former business associate Roman Abramovich.

London

Litvinenko had quit the FSB and gone to London. Short says, “Berezovsky hires him. He has given up on bribery and declares himself to be “a patriot trying to wake up Russia.” Short writes, “MI6 [British intelligence] had paid him a retainer for a time for information about the Russian leadership, but he was regarded as something of a loose cannon and the relationship was discontinued. He remained close to Boris Berezovsky who gave him a generous stipend to work for his quixotic campaign to bring down Putin’s regime.” Short cites NYTimes correspondent Alan Cowell that Litvinenko was “prone to obsessions and crusades…He was undiscerning of the truth. He relished campaigns, reached wild conclusions. He was a zealot. He was flaky. He saw connections where no one else did.”

Short says explosions in Moscow were seized on by Putin’s opponents, taken up by Berezovsky who financed a TV documentary “The Assassination of Russia” and books “Blowing Up Russia” and “The Lyubyanka Criminal Group” coauthored by Litvinenko which claimed that Putin had ordered apartment building bombings.

Short says “Twenty years later, many Russian politicians, newspaper editors and political commentators, as well as their counterparts in the West remain firmly convinced attacks carried out by, or with the connivance of, the FSB….Yet it is almost certainly false.” He says Kremlin strategists would have rejected such measures. They were not idiots. And he cites historian Richard Hofstadter about “the American tendency to view every enemy as amoral superman, sinister, cruel…” He says “Putin is no more an aberration in Russia than Donald Trump in America, Boris Johnson in Britain or Emmanuel Macron in France. He represents the hopes and fears, the aspirations and anguish, the conceits and resentments of a substantial part of the Russian population, who regularly support him.”

So to The Play

Morgan’s version is largely accurate, except he appears to take the view of Berezovsky’s friends that this oligarch “made” Putin. Short would disagree. And he makes Putin appear so disagreeable, he proves the truth of Hofstadter’s comment, which goes for Brits as well as Americans.

Berezovsky (Michael Stuhlbarg) calls Putin (Will Keen) deputy mayor of St Petersburg and asks for support to set up auto dealership. Putin tells him there is a process for this in town hall. Boris asks how can he skip the line. Putin tells him he doesn’t accept bribes.

Berezovsky tells Korzhakov (Paul Kynman) head of President Yeltsin’s security service, “I will make our President rich, powerful and secure in his job if I’m permitted to buy a controlling stake in the State television channel. ORT.” Then there is a car explosion, an attempt on his life. Boris is hospitalized.

The team that investigates the explosion includes Litvinenko (Alex Hurt). Berezovsky offers him a job. He first declines, then later takes a proffered Mercedes. Berezovsky tells Litvinenko’s wife (Stella Baker), “I am also a patriot trying to wake up Russia after seventy years of slumber. I can introduce him to some of the most influential people in the country. For me it is just a phone call. In return I will have someone who will protect me whatever it takes.”

The play has Putin tell Berezovsky, “Actually, now you mention the President [Yeltsin] and your close association, it is for this reason that I came to see you. You might remember how I was able to help you sell your cars in St Petersburg.”

The dialogue below was always Berezovky’s line, and that of his friends, but it is contradicted by Short’s accounts.

PUTIN “And you might also recall how, at the time, you wanted to compensate me in some way.”

BORIS I wanted to bribe you!

PUTIN And I refused.

BORIS Because you’re loyal! Now you’re broke and you regret it! I understand, Volodya…how much?

PUTIN No, I don’t want money. Before I was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, you may or may not know, I was in the intelligence services.

PUTIN I am interested in liberalizing Russia. For too long we have defined ourselves as enemies of the West. We need to become close to the West.

BORIS (raised eyebrow) Hear, hear.

PUTIN Of course that is the aim of the Yeltsin administration, and I have heard……they might be looking for people, co-operative people, like-minded people to help take this country in the right direction.

BORIS Well, I would be happy to put in a word to Tatiana on your behalf. I will speak to the Yeltsins and sing your praises and I’m sure they will find something for my friend from St. Petersburg.

PUTIN I’m forever in your debt.

The FSB Boss (Jeff Biehl) talks to Litvinenko about Berezovsky offering him job. He says, “Then I’m sure you’d agree, criminals cannot be allowed to interfere in the political process. Berezovsky and his businessmen friends have subverted the constitution and bought the election for their own interests. They need to be dealt with.”

Litvinenko replies, “I’m sorry, are you really asking an officer to execute a fellow Russian…without a fair trial? Without justice? I think the Russian people would be interested to hear about this….I have thought enough. As of today, I am no longer an officer of the FSB. (He removes his ID, hands back badge) As of today I work for Boris Berezovsky!! It didn’t happen quite that way, but okay.

Then a meeting between Berezovsky and Putin, the new Director of the Federal Security Service. Again, this contradicts what Short says about Putin being named Yeltsin’s successor.

PUTIN Not what I wanted, Boris. I wanted politics. I thought you had influence with Yeltsin.

BORIS All right. I will go back, and put in another word with the Family. [The people around Yeltsin.}

PUTIN As we agreed.

About Litvinenko Berezovsky tells Putin, “He told journalists the truth; that his superior officer ordered him to murder me.”

PUTIN says the Colonel in question, denied all the charges.

BORIS Of course! Because he doesn’t want to end up in the Salt Mines where Litvinenko is now. Release him, please?

PUTIN A traitor? Never.

BORIS Volodya, give him his freedom back and in return, I promise, I will speak to the Family about getting you out of the Lubyanka building and into the Kremlin.

This contradicts Short.

PUTIN I was at home. The phone rang. It was the President. He summoned me to his dacha and there, in a room just the two of us…He asked me…BEGGED me…to be his successor. Extraordinarily unlikely Putin would have told this to Berezovsky.

Putin’s meeting with top business people to tell them they can keep their wealth, often ill-gotten, as long as they don’t use it to run politics, is quite true. Morgan has Berezovsky bursting into Putin’s office in a fury. Putin tells him, “Gentlemen, the party is over.” “Business is business.” “And politics is the business of the state.” “I understand that when Russia had an incapacitated, enfeebled President there was a power-vacuum into which self-interested businessmen like you, could step. Well, that vacuum no longer exists and as of today any businessmen who engage in political interference can expect to be prosecuted.”

Berezovsky didn’t go to the meeting where oligarchs got the notice.

BORIS I was busy.

PUTIN It’s a foolish man that is too busy to meet his President.

BORIS Not when he created that President.

PUTIN We might have to disagree about that.

BORIS Not when he single-handedly plucked him from some provincial deputy mayor’s cupboard then placed him in the most powerful office in Russia.

PUTIN We might have to disagree about that, too.

So would Short, maybe Morgan gets this right.

BORIS Oh, my God… Only a former Head of the Federal Security Services could be this naïve! You cannot separate business and politics when the state is bankrupt. You need our money. Without the oligarchs you stand no chance.

PUTIN I’m not sure I see it that way. I see a country that has fallen into the hands of a handful of self-interested crooks. Priceless state assets have been snapped up by robbers, thieves…” All true.

PUTIN The State needs to reclaim its assets and its authority. A country cannot be run by businessmen. Social policy cannot be determined by businessmen! Foreign policy cannot be determined by businessmen!

PUTIN Then why did you put me here? As you keep claiming you did?

BORIS To DO MY BIDDING!!!!! FOLLOW ORDERS like the appointee you are.

PUTIN Appointee?

BORIS Yes. Appointee. Supplicant. Minion.

PUTIN I think our time is over.

Then the sinking of the submarine Kursk. Berezovsky changes the TV text on ORT to attack Putin. “Our President was water-skiing…. then too proud to engage with Western governments who were trying to help. Meanwhile his sailors, noble sons of Russia, suffocate and die needlessly on the ocean floor?”

Putin orders Boris Berezovsky to relinquish control of the station or he will be arrested on charges of tax evasion, illegal entrepreneurship, and embezzlement. Berezovsky resigned his seat in the Duma and left the country.

He would launch more attacks on Putin, accusing him of being behind the Moscow apartment bombings, which Short says is not true.

Then Litvinenko’s wife Marina calls Berezovsky to say he is very ill. After some days he dies. It was polonium poisoning. Berezovsky angrily phones Putin. PUTIN I have nothing to say to you. It’s unlikely Putin would have accepted his call.

At the end, Roman Abramovich (Luke Thallon) calls Putin to tell him Berezovsky was found dead in his English home. And he adds, “But Western media is suggesting that it might NOT have been suicide. An FSB hit squad was known to be in the UK at the time. MI5 had been receiving warnings for months.”

But London police reported the door was locked from the inside. Are Russian FSB agents capable of turning into ectoplasm? Morgan admitted to the NYTimes he changed the story from “unambiguously a suicide” after the death of western hero/convicted fraudster Alexey Navalny to make it “more ambiguous” out of respect for “political prisoners.” Navalny had violated parole after being given only probation for a scam that cheated Yves Rocher Vostok, part of the French cosmetics firm. Morgan ending his story with propaganda he doesn’t believe is true shows disrespect for his audience.

“In the West you have no idea.” Many of us do.

“Patriots.” Written by Peter Morgan, directed by Rupert Goold. Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 243 West 47th St, NYC. Runtime 2hrs30min. Opened April 22, 2024, closes June 23, 2024.