By Lucy Komisar

Max Wolf Friedlich’s “JOB” is a riveting psychological detective story that blurs the lines between truth and deception, sanity and madness. And evil. This taut two-hander, subtly directed by Michael Herwitz, keeps the audience on edge.

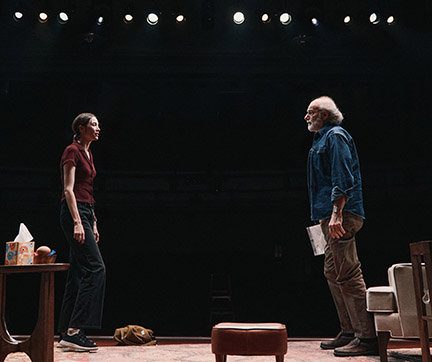

The play opens with a startling tableau: Jane (Sydney Lemmon), a young tech worker, pointing a gun at Loyd (Peter Friedman), her septuagenarian psychiatrist. What follows is a masterclass in psychological warfare, as the two characters engage in a verbal sparring match that constantly shifts the ground beneath the audience’s feet.

Lemmon delivers a tour de force performance as Jane, oscillating between unhinged aggression and calculated manipulation. Her physicality alone tells a story, with her body twisting and contorting as if trying to escape itself. Friedman’s Loyd provides a perfect foil, his calm demeanor slowly cracking to reveal hidden depths of pain and guilt.

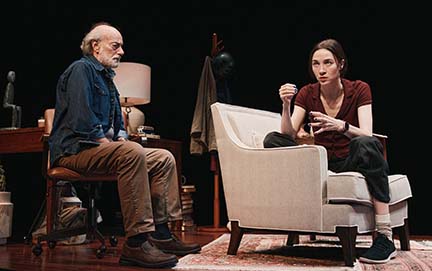

The stark set, featuring two white leather armchairs, becomes a battleground for generational conflict and personal trauma. Flashing colored squares on the backdrop punctuate moments of heightened tension, offering visual cues to the characters’ inner turmoil.

Friedlich’s script is a puzzle box of revelations, each new piece of information forcing the audience to reassess what they thought they knew. The playwright deftly weaves in contemporary issues – from content moderation in tech companies to the lingering influence of 1960s counterculture – while never losing sight of the personal stakes at the heart of the story.

Loyd persuades her to put the gun away, and she stashes it in her bag.

We learn that Jane was required to go to therapy by her company because of a fit she threw at work. Loyd has to determine if she can go back. Panic attacks began when she started her job. Now, there’s a video of her standing on an office table screaming. She says, “They wish could fire me, though it could be a lawsuit.”

Most of the discourse is about her life, therapy that started at 9, parents who were a mother anthropology prof who cheated on her unsuccessful artist father. (They divorced). Then and at other times the set goes dim and colored lit squares flash on the backdrop. They seem to reflect moments when the dialogue sparks one or both characters‘ interior thoughts.

Loyd seems quite calm most of the time. Jane’s body language often twists her out of shape.

She talks of college days when she hung out with the “hippies” and got pregnant by Sid, had an abortion. And later, when she had psychological breakdowns, she says “In the hospital you don’t have to make sense. They ask how you are doing. Outside nobody has time for me. You make friends with someone normally you wouldn’t talk to. Blacks and Asians. Everybody’s racist and we’re all alone.”

Jane sticks a hand into the bag where she stashed the gun. Loyd starts screaming. She takes out lozenges.

She gets into a riff on his aging boomer hippies vs her generation. “Why are they so mad at us using technology when they are getting rich off it?….Techs vs hippies are at war, and we’re winning.” She said with the hippies at school you had to wear grotty t-shirts to be accepted. You focus on his blue denim jacket. He went to UC Berkeley. So where is this going?

Then there is a shift. She suddenly seems saner than her history would warrant. And you look back at the dialogue to try to make it fit another scenario. As the power dynamic between Jane and Loyd alters, the play takes on the qualities of a psychological thriller.

She works in “user care,” also, she explains, called “content moderation.” But it’s not the political kind. We learn that her job involved monitoring internet content to flag and block videos of abuse, sexual exploitation of children, torture and the like. That has led her at times to track down the perpetrators.

She starts asking him questions about his life, his children. Now the lights are flashing continuously. Did she get to that shrink visit by chance?

He accuses her, “I don’t think you want to go back there…From the moment you pulled out the gun there was no – this is not what I do! Please realize what is happening here. You are holding me hostage. Your finger could have slipped and my son wouldn’t have a dad.” And then, “I lost my daughter when she was 13 years old. My daughter took her own life when she was 13 years old.”

She: “I remind you of your daughter?” She describes how her job led her to what she knows about him. None of this can be told here without giving away the plot, but it sends spines shivering.

The specter of Chekhov’s gun looms large, as tension increases in the final moments. He: “I will give you your job back.” One thing missing: if the matter of doubt that arises was fully worked out, one should see or feel in retrospect that there were clues that one missed.

“JOB” is not just a whodunit, but a “who’s telling the truth”.

“JOB.” Written by Max Wolf Friedlich, directed by Michael Herwitz. The Hayes Theater, 240 West 44th St., NYC. Runtime 80min. Tkts. Opened July 30, 2024, closes Oct 27, 2024. Review on NY Theatre Wire.