By Lucy Komisar

Inter Press Service (IPS), July 9, 2008

As Sen. Barack Obama prepares to accept the Democratic presidential nomination at a 75,000-seat football stadium in Denver, Colorado next month, Thurgood on Broadway takes audiences back to another iconic and groundbreaking figure in U.S. civil rights history.

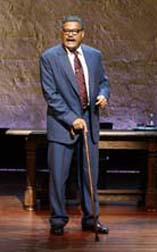

Playwright George Stevens, Jr., director Leonard Foglia, and actor Laurence Fishburne bring life to the musings of Thurgood Marshall, the first black member of the U.S. Supreme Court. He had fears and doubts, but braved life-threatening encounters with Southern racists as he dedicated himself to overturning the legal structures of segregation in the United States.

The play is in the form of a talk to students at Howard University where Marshall had studied law 50 years earlier, the class of 1933.

Moving back through time, he recalls incidents that seared his conscience. Living in Baltimore — the northern edge of the segregated South — he worked after school for Mr. Schoen, who ran a dress shop. Once, on an errand to deliver hats, he was trying to get on the trolley when a woman pushed past him.

I feel a hand grab my collar and this white man pulled me off the trolley. ‘Sir, I’m just trying to get on the damned car’, Marshall relates.

He says, ‘Nigger, don’t you push in front of white people!’ I started swinging. The man smacks me to the ground and tramples all over the hats. A policeman hauls me off to the station. I call Mr. Schoen and he comes over to the jail. I’m crying by that time and I apologise for the damage to the hats. Schoen says, ‘That man really call you a nigger?’ Yes, sir, he sure did. ‘Thurgood, you forget about the damn hats, you did the right thing.’

From his second-storey classroom window, Thurgood looked down on the Northwest Baltimore Police Station. He says, To this day, I can’t lose the sound of those cops beating the hell out of those Negro prisoners.

Young Thurgood started out wanting a diverting, easy life. He liked the ladies and enjoyed a drink. He says, I was pinned to seven co-eds, all at the same time. I’d already decided to become a dentist and never lift anything heavier than a poker chip.

Reality intervened. He recalls, One day we go in to town to see a movie and after we buy our tickets, they tell us we have to go around to the back and up the stairs to sit in the coloured balcony — the ‘crow’s nest’. We asked for our quarters back and they refused. We got angry and pulled down a bunch of curtains and broke a door and ran like hell.

That night he thought, Am I going to go through life being humiliated because of the colour of my skin? He stopped playing pinochle, started reading history and joined the debate team.

Marshall, the man, serious and dedicated, worked with the Howard Law School head to challenge segregated schools, using the 1896 Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision that facilities could be separate but had to be equal. He jokes, We call that Jim Crow Deluxe. The tactic worked to open the University of Maryland Law School, which had denied him entrance.

At the legal department of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), the focus was Southern voting rights — fighting poll taxes, literacy tests and physical intimidation. He had the courage and fortitude to go into the belly of the beast, in the dangerous deep South.

At the legal department of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), the focus was Southern voting rights — fighting poll taxes, literacy tests and physical intimidation. He had the courage and fortitude to go into the belly of the beast, in the dangerous deep South.

He tells a chilling story, Fishburne recounting it as if it were almost commonplace, as indeed it was at the time. One time we’re defending two Negroes charged with murder in a race riot in Columbia, Tennessee, near the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan. Word was out they’d kill us if we tried to sleep in that town, so we drive 45 miles to Nashville every night. We’re leaving town just after sunset. I spot three or four state police cars — and we’re pulled over. I’m at the wheel. They say they have a warrant to search our car.

The sheriff says, ‘This is the one. You get out the car.’

‘What for?’

‘Drunken driving.’

‘I haven’t had a drink in 24 hours.’

They shove me in a police car between two beefy deputies holding shotguns and drive off. Suddenly the car turns off the road and heads through the woods toward the river. We get to a place where a bunch of men are waiting under a big tree with a rope hanging over it — fixin’ to do a little bit of lynching. Then the car with my friends catches up — so I guess these deputies get cold feet. They turn around and drive me to town.

The little magistrate is five foot nothing. He says, ‘What’s up?’

‘We got this boy for drunken driving.’

‘I’m not drunk.’

‘I’m a teetotaler — never had a drink in my life. I can smell liquor a mile off…Hell, what are you boys talking about? Get out of here! This man hasn’t had a drink.’

He says, I got myself on the fastest goddamn train out of there. And I had a drink. I sat with a bottle of Wild Turkey and thanked the lord. And I thought about the Negroes who stayed behind. They were the heroes.

The most important race case of the era started because Clarendon County, South Carolina, refused to provide a bus for the one-room Scotts Branch School and the seven-year-old son of Harry Briggs, a garage mechanic who fought in World War II, had to walk five miles. Briggs signed a complaint, got fired the same day, and the NAACP took the case. It ended up in court in Charleston where the argument of social psychologist Kenneth Clark made history.

Dr. Clark went to the Scotts Branch School with a court order, a white doll and a black doll. He would testify that when the African American children were asked to choose between the white doll and the brown doll and to say which was nice, 65 percent said the white doll was nice. Seventy percent thought the brown doll was bad.

We see Marshall put the dolls on the table at court. He tells the judges, This overwhelmingly suggests that segregation has a detrimental effect on the personality development of these Negro children. They, like other human beings who are subjected to an inferior status, are irreparably harmed.

We see Marshall put the dolls on the table at court. He tells the judges, This overwhelmingly suggests that segregation has a detrimental effect on the personality development of these Negro children. They, like other human beings who are subjected to an inferior status, are irreparably harmed.

The court ruled 2 to 1 for South Carolina, but the Supreme Court took that case and other school cases together as Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the decision was unanimous that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

Marshall was appointed appeals court judge by President John F. Kennedy and then to the Supreme Court by President Lyndon Johnson. He spent nearly 25 years on the court.

Suddenly, as Marshall reminisces, you notice that his hair has turned grey and his walk has become hesitant. He needs a cane. It’s the last years of a life well spent — Marshall died on Jan. 24, 1993 at the age of 84 — and this play is a worthy, moving testament.