By Lucy Komisar

It‘s the late 1930s, in Charleston, South Carolina‘s Catfish Row where the poverty of the Depression seems permanent. Clara (Nikki Renée Daniels) cradling her infant, and her husband Jake the fisherman (the charming Joshua A. Henry) thrill you to the bones with “Summertime.”

The poor black residents eke out a living fishing, picking cotton and hawking goods to housewives. They go to church a lot. Sometimes they have a lively good time at picnics. The men, looking for excitement and quick riches, gamble on dice. Their wives struggle to keep them responsible.

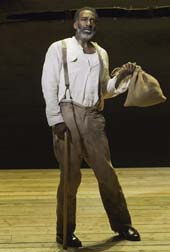

There‘s also a dark side; the cocaine seller “Sporting Life” (David Alan Grier) and the loose woman Bess (Audra McDonald) who is hooked up with the violent Crown (Phillip Boykin.) And then there is the distress of the crippled Porgy (Norm Lewis), who begs for a living.

The Gershwins‘ opera adapted by Susan-Lori Parks and directed by Diane Paulus as a Broadway musical is charming, vivid, delightful and moving.

The mood, inflection and movement is jazzy folk. The slow rhythm, as in the thick humid heat before a storm, explodes when the burly Crown swaggers in to join a game of craps. He‘s a cheater. There‘s an argument, a fight.

A player Robbins (Nathaniel Stanley) comes at him with a cotton hook, but Crown seizes it and stabs him to death. Now, there‘s a widow, Serena (Byronha Marie Parkham), who in a stunning soprano sings, “My Man‘s Gone Now.” And so the drama. Crown flees.

But his lover Bess arrives in a décolleté red dress and is shunned by the locals till the smitten Porgy takes her in. She, overwhelmed by his goodness, falls in love with him. And is determined to change.

Daily life goes on amidst the tragedy with some joyous moments and the visits of peddlers who sing out their wares, strawberries, honey, and crabs. There‘s a sense of community, from passing the plate to pay for Robbins‘ funeral, to taking care of others’ babies. The people are poor in money but rich in caring for each other.

The music, the singing, and the movement envelope you. McDonald has a sweet rich soprano of great range. As a dramatic actress, she exudes the fear, distress, and nervousness of Bess, who is weak-minded and easily led. Norm Lewis is a fine actor as Porgy, but his voice lacks the depth, timber and operatic quality of others in the cast. Still, he is powerful in I Got Plenty of Nothing.

There are threats natural and human. Some come from the wider world represented by brutal cops such as the police detective (Christopher Innvar) seeking Robbins‘ slayer. He wields a chair against the innocent Jake and then drags off Porgy. A killer hurricane slams the church where the neighbors have taken refuge.

Then, there are the inner threats. The fierce Crown, who has been hiding on a small island, returns as deadly as the roaring wind. The crass Sporting Life while Porgy is locked up tempts Bess with some happy dust and the enticement of a life in New York (“There‘s a Boat That‘s Leaving Soon”).

There‘s a tension between the religious response represented by Serena and the cynicism of “It Aint Necessarily So” sung by Grier, attired in a snazzy striped suit for Sporting Life‘s memorable number.

A vibrant mix of folk and jazz dancing (choreographed by Ronald K. Brown) erupts at the picnic hoedown to the tune of Oh, I Can’t Sit Down. Among the other unforgettable Gershwin songs in this folk opera are “Bess, You Is My Woman Now,” “I Loves You, Porgy,” and “I‘m on My Way.”

Paulus‘s direction is fluid and dramatic. Sometimes, the placement of the cast seems like a diorama or a painting. The set is spare, made of planks and a corrugated metal backdrop, some wood chairs. Designer ESosa‘s costumes in drab pale colors conjure up sepia photos. The lighting by Christopher Akerlind shows tremulous dark threats of weather, the sea roiling in projections of waves, lights that dramatically illuminate actors.

There has to be some chutzpah (the word the Gershwins would have used) to describe changing their work to protect U.S. audiences from seeing the extreme nastiness of poverty and then calling the result “The Gershwins‘ Porgy and Bess.” The original has Porgy in a wooden goat cart. Parks/Paulus set him up with a cane, dragging a twisted foot. Mid-way through, Porgy manages to buy a leg brace and trades the foot-dragging for a limp. Of course, in this staging one can see the practical benefits of not having Porgy in a goat cart!

The production has also been cut to two-and-a-half hours from the four-hour opera, but the Parks revision is seamless; never for a moment do you think something is missing. The complaints about the disappearance of dialect? That‘s like expecting actors in a Shakespeare play to have 17th-century accents. And “Porgy and Bess” is indeed a classic.

The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. Based on a book by DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, adapted by Susan-Lori Parks; lyrics by Ira Gershwin; music by George Gershwin, adapted by Dierdre L. Murray. Directed by Diane Paulus. Choreographed by Ronald K. Brown. Richard Rodgers Theatre 226 West 46th Street, New York City. 877-250-2929. Opened Jan 12, 2012; closes Sept 23, 2012. (9/10/12)