By Lucy Komisar

November 2004

Insurance giant AIG, run by powerful international financial player Maurice Hank Greenberg,  has used offshore structures in Barbados and Bermuda to circumvent or violate U.S. state laws regarding reinsurance in a way that based on evidence about one crooked client, allows them to evade taxes.

has used offshore structures in Barbados and Bermuda to circumvent or violate U.S. state laws regarding reinsurance in a way that based on evidence about one crooked client, allows them to evade taxes.

In the late 90s, four state insurance departments were aware that AIG was secretly hiding its debts offshore but, despite substantial evidence of wrongdoing, no sanctions were ordered.

In another case, AIG helped notorious crook Victor Posner evade U. S. taxes by way of an offshore reinsurance company. Again, a state regulatory agency was aware of this but did nothing.

AIG’s suspect business practices – which are currently under the microscope as a result of New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s investigation into the insurance industry – go back many years and are broad in scope.

In October, Spitzer filed suit against the world’s largest insurance broker, Marsh, accusing it of bid-rigging and kickbacks that appear to have defrauded companies, city governments, school districts and individuals of billions of dollars in higher premiums. It accused several insurance companies, including AIG, of participating in with the scheme, making phony or inflated bids and paying off the brokerage to get business.

It worked this way: Marsh, which was supposed to find the best policies for its clients, instead steered them to companies that agreed to pay kickbacks. It solicited phony bids for insurance contracts to deceive customers into thinking there was real competition for their business. Marsh made $800 million on kickbacks in 2003 alone – over half its $1.5 billion profit. With a 40- percent share of the global insurance brokerage market, its fraud drove up prices for everyone.

This is the industry that for years has been blaming everyone else for premium increases, Spitzer said. Greedy trial lawyers were the usual excuse for premium increases. Now we know that greedy corporations also have a starring role.

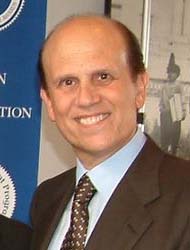

AIG announced that the company’s senior managers were not aware of the bid-rigging. Hard to believe. You see, this scam was a family affair. The head of the Marsh brokerage was Jeffrey Greenberg, (right) and the CEOs of two of the colluding insurance companies were his brother Evan, 49, head of ACE Ltd., and his father Maurice (Hank) Greenberg, 79 (left), who runs AIG, where the brothers got their insurance training. A former AIG staffer told me, Greenberg is legendary as a hands-on person. Nothing happens in the company without him dealing with it. He knows the names of the elevator operators.

At Spitzer’s press conference, New York State Insurance Superintendent Gregory V. Serio said: This has gone from an inquiry into failure to disclose compensation to an active investigation of bid rigging and improper steering. This certainly proves the adage that where there is smoke, there is fire.

But AIG’s comportment could not have been much of a surprise to Serio, who was New York’s deputy insurance superintendent in the late 90s. That’s when New York and three other states gave the powerful company a pass on some very questionable practices. If they had paid attention to the smoke then, perhaps this billion-dollar fire wouldn’t have ignited.

In the late 90s, state insurance departments in New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania and California were aware that AIG was moving debt off its books via the use of an offshore shell company it secretly set up and controlled. But despite clear evidence of wrongdoing, no sanctions were ordered.

Maurice Greenberg runs the world’s second largest financial conglomerate and the largest underwriter of commercial and industrial insurance. Last year, AIG reported net income of $10 billion. It has $648 billion in assets, a market value of $195 billion, $77 billion in sales and $6.5 billion in annual profits. It has operations in 130 countries and nearly 77,000 employees. It ranks third on Forbes’ list of the world’s biggest companies, after Citigroup, and General Electric.

AIG is public company. Its largest single shareholder with 13.62 percent of AIG stock is Starr International Company (SICO), a private company headquartered in the tax haven of Bermuda. Greenberg owns 21.86 percent of SICO. Forbes says Greenberg has a net-worth of $3.6 billion, making him the world’s 132nd richest man. Greenberg was elected AIG president in 1962, CEO in 1967 and chairman in 1989.

Though it is an American company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, AIG makes extensive use of offshore jurisdictions such as Barbados, Bermuda and Luxembourg that are immune from U.S. regulatory and tax scrutiny. They help the company launder profits to avoid U.S. taxes and hide insider connections in supposedly arms-length deals. This is especially important as the company has moved into financial services and asset management, handling the wealth of high net-worth clients — the mega-rich.

Greenberg has enviable political clout, never so much in evidence as when, with the help of Henry Kissinger — chair of AIG’s international advisory committee and a paid consultant via Kissinger Associates – AIG became in 1995, the first company licensed to sell insurance in China. AIG was also then the only foreign firm that owned 100 percent of its license there.

Maybe that’s what protected AIG from even a single line in the major news media or any regulatory punishment when four state insurance agencies in the late 90s discovered it doing what in the Enron era is called cooking the books. AIG was moving debt off its books via the use of an offshore shell company it secretly set up and controlled. The four agencies ordered no sanctions.

In another case, not reported before, AIG worked with Victor Posner, a partner in fraud with former junk bond king Michael Milken, to set up a reinsurance company offshore so that AIG could take a larger rake–off in commission and Posner could evade U.S taxes. The Delaware Insurance Department learned about it, but did nothing. (Milkin was jailed for 10 years for securities fraud in another case, but got out after two.)

Things have been tougher for the company since the Enron affair caused the SEC to get more serious about corporate corruption. Remember Enron’s structured finance, the corporate euphemism for cooking the books? Last year AIG paid a $10-million fine to the SEC for helping the Indiana wireless telecom company Brightpoint commit accounting fraud. Brightpoint’s goal was to conceal $11.9 million in 1998 losses. AIG designed a $15- million retroactive insurance policy. Brightpoint paid $15 million in premiums, and AIG would refund $11.8 million as phony claims payments that the firm could claim as assets. Using the AIG scheme, Brightpoint overstated its 1998 net income by 61 percent.

AIG marketed this as a non-traditional insurance product aimed at income statement smoothing, spreading a loss over future reporting periods. The SEC called such financial products just vehicles to commit financial fraud and said the insurance giant refused to give it subpoenaed documents, compounding its misconduct.

AIG also got caught helping the PNC Financial Services Group of Pittsburgh inflate its 2001 net income by $155 million, or 27 percent. It used a plan devised by accountants Ernst & Young to shift $762 million in loans from the bank holding company’s balance sheet to special purpose entities, la Enron. Then AIG sold the crooked plan to other banks. PNC had to pay a $115 million fine, and the SEC and the Justice Department are still investigating AIG’s role.

But where are the state insurance departments?

If the SEC is becoming more active against corporate fraud, the state insurance departments seem mired in their undistinguished past. Consider these two examples.

Victor Posner, who died in 2002, was the original corporate raider, famed for engineering hostile takeovers of companies and looting them. He was also a crook. In 1977, the SEC filed a civil complaint against Sharon Steel in Pennsylvania, which Posner controlled, for overstating earnings. In a separate criminal action, Posner pleaded no contest in 1987 to evading more than $1.2 million in taxes and was ordered to pay $7 million in fines and back taxes. In the early 90s, Posner and his son, Steven, were found to have failed to disclose a fraudulent takeover scheme between them and Wall Street crooks Michael Milken and Ivan Boesky. Posner was banned from serving as officer or director of any publicly-held company and ordered to repay about $4 million to fraud victims.

As the result of a court-ordered bankruptcy reorganization, Posner’s NVF Corp., which ran a Delaware vulcanized rubber plant, brought in expert Terry Mills in 1993 to look at its insurance. Mills told Catherine Mulholland, director of the Delaware Insurance Department’s bureau of examination, of his astonishment at discovering that NVF had been paying National Union Fire of Pittsburgh, an AIG company, substantially over market for workmen’s compensation insurance.

Insurance companies normally insure themselves by laying off part of their risk to reinsurance companies, so if a claim comes in above a certain amount, the reinsurance company will pay it. AIG reinsured the NVF policy through Chesapeake Insurance, a reinsurance company Posner owned in Bermuda – an offshore tax and secrecy haven.

That meant AIG would keep a portion of the inflated NVF premium and send the rest to Chesapeake. AIG would have a higher commission. Posner would write off the entire amount as a business expense and enjoy the extra cash in Bermuda, tax free.

A regulator from one of the four investigating state insurance departments said, This was not an isolated case with Vulcan. AIG did that a lot. He said, AIG helped companies set up offshore captive reinsurance companies. A captive is owned by the company it insures. AIG would then overcharge on insurance and pay reinsurance premiums to the captives, giving the captive owners tax-free offshore income.

Mills told me he cancelled the NVF policy with AIG, but the Delaware Insurance Department did not make the scam public or take any action against the insurer.

This story has not been reported before.

Provided the details of what AIG did, company spokesman Andrew Silver replied, We don’t have any comment on that.

In the mid-90s, insurance investigators in Delaware, New York and Pennsylvania caught AIG laying off its insurance to a third-party reinsurance company AIG itself had created and controlled. But, apparently, intimidated by the company’s power, the regulators again failed to sanction it.

Insurance companies use reinsurers not only to lay off some of their risk, but because state laws require them to keep a certain amount of capital available to pay out claims. If they have reinsurance, that amount can drop. Companies have to show losses – amounts they have paid out — on their books. If they have enough good reinsurance, they get a credit for that against their losses. The reinsurer, of course, has to be an independent company; the risk isn’t reduced if it’s just moved to another division of the same company.

In the mid-80s, two of AIG’s reinsurers failed. Transit Casualty Insurance Company became insolvent in December 1985 and Mission Insurance Company, which had been placed under conservatorship in October of 1985, became insolvent in February 1987. The liquidators would pay creditors, including insurance claimants, but that would take several years.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) says any debt outstanding for over 90 days can’t be claimed as an asset. If Mission and Transit were not paying AIG claims on time, those amounts would be debits, not assets. AIG would have had to curtail writing new business, since rules require a certain ratio of assets to risk. Greenberg needed to move these uncollectables off AIG books. And he needed to do it cheaply – without paying the high premiums arms-length companies would charge.

Trevor Jones, an insurance investigator who for 20 years has run Insurance Security Services in London, explained, Hank decided to set up Coral Re, move the debts he couldn’t claim as assets into this other company and say this new company owes us this money. Because the debt due from Coral Re wasn’t over 90 days, he could claim that as an asset. No other real company would play ball, because you are fiddling the accounts, moving your bad debts off your books.

So AIG went to elaborate lengths to set up a shell company in Barbados, where capital requirements and regulation was minimal compared to the U.S., where American regulators couldn’t readily discover AIG’s involvement and where, as an added incentive, it could move money out of reach of U.S. taxes. He persuaded several of his friends to set up a company into which he could cede AIG insurance.

Goldman Sachs & Robert Rubin

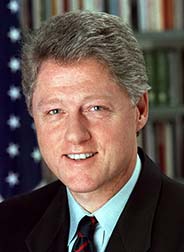

Coral Re, a Barbados reinsurance company, was launched with a private sale of shares organized by Goldman Sachs, then headed by Robert Rubin, who would become President Clinton’s Treasury Secretary and is now chairman of the executive committee of Citigroup. Its counsel in the matter was the Wall Street firm, Sullivan & Cromwell.

The Goldman Sachs stock placement memorandum dated December 1, 1987, declared, The information contained in this memorandum has been obtained from the company [Coral Reinsurance Co. Ltd] and American International Group, Inc. (AIG)….AIG and the company will make available to any prospective qualified investor, prior to the closing date for the sale of the common stock, the opportunity to ask questions of and to receive answers from AIG and/or the company concerning the terms and conditions of the offering.

The memo said investors were being solicited to establish Coral Reinsurance Ltd. in Barbados. The Company is designed to reinsure certain risks from several of the U.S. subsidiary insurance companies of American International Group, Inc. (AIG). AIG’s interest in creating the Company is to create a reinsurance facility which will permit its U.S. companies to write more U.S. premiums.

For a U.S.- domiciled company, a high level of surplus is required to support insurance premiums in accordance with U.S. statutory requirements. The statutory requirements in Barbados are less restrictive.

Goldman Sachs said recipients had to keep the information confidential, make no copies of the memo and return it on request.

A no-risk deal was offered to the selected investors, Fortune 500 CEOs chosen for their names: L. Donald Horne, chairman of Mennen Co.; Charles Locke, chairman of Morton Thiokol; Kenneth Pontikes, former chairman of Comdisco; David Reynolds, chairman of Reynolds Metals; John Richman, former chairman of Kraft; and Samuel Zell, chairman of Itel Corp.

Rubin buddy Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, may also have thrown his weight behind the project. The Arkansas Development Finance Authority (ADFA) was the lead investor with 84 of the 1,000 Coral Re shares issued. Bob Nash, then ADFA president, later became Personnel Director of the Clinton White House. ADFA agreed to buy the Coral Re stock of any investor who defaulted on his Sanwa loan; financing would come from Sanwa. There would later be a heated dispute about whether it was legal for the legislature to exempt this deal from the state’s constitutional ban on a state agency holding stock.

Some shareholders were directly connected to AIG. Stock was bought by insurance companies Abeille Re and Abeille Assurances, of Paris. The affiliated Abeille General Insurance Co. was managed by AIG’s North American Managers Inc in New York and headed by top AIG officers.

The shares cost $4 million per unit, but investors didn’t have to use their own money. They were loaned the total amount by the Chicago branch of the Sanwa bank of Japan, a country where the AIG does a large amount of business. ADFA borrowed $5 million from Sanwa.

Except for the Abeille companies, the collateral for the bank was the stock itself, invested in bank CDs. And in case any of the well-heeled investors defaulted or had to sell shares, Goldman Sachs guaranteed to take the stock or find another buyer. The stock was not registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, so records were not public.

The investors could never make a profit or loss – the terms of the arrangements with AIG assured that – but they were guaranteed a fixed gain of $25,125 in the first year and $45,225 in each subsequent year, not bad for the use of their names. This was not a legitimate capital structure, because there was no money at risk. And the board of directors never made a decision.

Considering that the investment money came from a bank, this transaction looks eerily like the secret loans Citicorp and J.P. Morgan Chase arranged for Enron by passing them through offshore shell companies. Goldman Sachs did not respond to inquiries about its role in setting up Coral Re.

In 1990, Coral Re bought back the shares and reissue new ones for about $15 million to Abeille Re and Abeille Assurance; the Molson Companies Ltd, whose president Marshall Cohen was an AIG director; First Transportation Indemnity Ltd which had previously been managed by American International Management owned by AIG in Barbados; and C.T. Insurance Ltd. of Barbados, managed by a Coral Re director. Coral Re had no office of its own; it was managed by American International Management.

By the second year, AIG had ceded Coral Re $1 billion of business. That would rise to $1.6 billion. A substantial amount of the premiums paid to Coral Re were then deposited in Uberseebank, a private bank owned by AIG in tax-haven Switzerland.

There are rules requiring companies to assure their solvency with letters of credit from banks. Coral Re’s came from a Japanese bank. AIG is the biggest foreign insurance carrier in Japan. It was a nice profitable circle.

Coral Re had only nominal capital of $60 million, but it didn’t need the capital and equity a normal reinsurance company would have required. That is because AIG itself paid all claims, using the bookkeeping device of increased premiums to Coral Re to take care of money the sham reinsurer had paid out. There was minimal profit – the premiums and payouts nearly canceled each other out. It was an accounting exercise to clean up AIG’s balance sheets.

The ex-AIG official said there were certain standards that regulators and accountants apply to see if something labeled a reinsurance contract is or is not a loan. They examine the capital vs. the premium flow. Is there too little capital for the amount of risk taken on? They look at shareholders and management — is all the management provided by the sponsoring company?

Another tell-tale sign is a put agreement — the right to sell shares – which means the investors are insulated from risk. Also, are there clauses in the contracts triggered by losses that would cause money to be advanced by the reinsurer but then repaid with interest by the ceding company, making it more a banking than an insurance transaction. This is old stuff, he noted. Everything about the Coral Re deal with AIG said banking, not insurance.

Eventually, the scheme unraveled. State insurance examiners look at company books every five years. In 1992, Delaware examiners auditing Lexington [an AIG subsidiary] smelled a rat, the former regulator told me.

AIG initially refused to provide Coral Re documents to the examiners, and it took them a couple of years to nail the connection. When AIG supplied Coral Re’s financial papers, the regulator was incredulous. He said, The books were definitely cooked. I remember three years in a row [in the early 90s] their pretax income came out to an even number. It was like somebody said ‘show $250,000 pretax income.’ I’ve been looking at financials for 35 years and have never seen pretax numbers come out even. The figures were 1987 $1.1 million; 1988 $1.555 million; 1989 $.8 million.

Clinton’s Arkansas Agency

Meanwhile, ADFA was being investigated by the Arkansas Committee started in 1990 by University of Arkansas students who thought that the agency, set up by Gov. Bill Clinton in 1985, might be involved in laundering drug-money. They were looking into activities at the Mena airport, believed to be a transit point for Reagan administration’s arms supply to the contras fighting the Sandinista government of Nicaragua.

The Committee became suspicious because it thought the ADFA was selling more bonds than it could use to finance state projects. Its demand for papers under the Freedom of Information Act went to the Arkansas Supreme Court, which in December 1994 dropped a sheaf of documents in the lap of Mark Swaney, a mechanical engineer working for the University and a member of the Arkansas Committee.

Swaney told me he found nothing about drug money, but a lot about a secret deal ADFA had made to buy stock in a Barbados reinsurance company set up by AIG.

Andrea Harter, a reporter for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, got on the story and obtained documents showing that at one point ADFA planned to be the sole investor in Coral Re. It would issue more than $50 million in bonds to set up a nonprofit company which would solicit insurance contracts from cities and county government and send the business to Coral Re. Harter wondered why ADFA wanted to invest in a Barbados company that is not regulated in the United States.

What was ADFA doing busing common stock, not permitted under state rules? And if so, why in a company set up in Barbados? Why was it given a sweetheart deal with a guaranteed return with no risk?

At about the same time that Goldman Sachs arranged for ADFA to invest in Coral Re, it was chosen to recommend other ADFA investments. It selected the AIG Matched Funding Corp. to manage the investment of nearly $1 billion in proceeds from ADFA single-family housing bonds.

Later, says Swaney, a staffer working on a report about Mena for Rep. Jim Leach, Republican head of the House banking committee, told him he had found out something about AIG and was going to put it in the report at Leach’s request. ADFA appeared to Leach to be corrupt because insiders received its loans. He thought the fact it was involved in this highly unusual Caribbean deal showed how loose the controls of state government were.

Leach wanted to know why a state agency was buying common stock, and why in an offshore Barbados company. Why was it given a sweetheart deal with a guaranteed return with no risk? Leach wanted Coral Re mentioned as a footnote to show there were inexplicable transactions in offshore financial centers going on at state-government level.

However, the Mena report never appeared. Bill Tate, Leach’s spokesman, told me, It was an internal document that was never published, and will not be made public. The decision was that there was nothing of significant value that came out of it. The investigation was started, he said, because there were allegations about money laundering going on at the vicinity related to possible illegal drug traffic through that airport. There was not enough hard information to warrant proceeding. He declined to reply when asked why the report hadn’t been published to lay the speculations to rest.

The Regulators Speak

The Delaware report on AIG, finally issued in October 1996, suggested that Coral Re may be an affiliate of AIG. It described how AIG played an integral role in the creation of Coral Re; that the purpose for creating Coral Re was to reinsure risks for AIG companies; that virtually all of Coral Re’s business originated from AIG units; and that Coral Re was managed by AIG subsidiary American International Management Co. Ltd. It said AIG had even designed the sample Coral Reinsurance agreements included with the stock offering. It concluded that the arrangement with Coral Re did not transfer risk and it had to come off the books.

AIG insisted, in the face of overwhelming evidence, that Coral was independent. The regulator told me, It’s clear AIG formed that company. They denied it, because if they owned it, it would be affiliated and they would not be able to take credit for reinsurance. Delaware should have suspended them, but did nothing.

The story got play in the trade press, with coverage by Douglas McLeod in Business Insurance and David Schiff in Emerson, Reid’s (now Schiff’s Insurance Observer.)

John Crudele of the New York Post took a look at AIG and pointed out that in its 1993 filing for its National Union Fire subsidiary, AIG had listed Coral Re as unaffiliated. He noted that an independent reinsurer could have a ratio of liabilities to equity of 59 to 1 (meaning its equity capital could be as little as 1/59 of what it might have to pay out), but an affiliated company was limited to 4 to 1; it would have to have nearly 15 times as much capitalization. In fact, Delaware admitted that Coral Re refused to give it an actual report of its reserves. AIG declared that it couldn’t supply them either, because the Coral Re board had voted not to release it to the Delaware Insurance Department.

The major American newspapers ignored the story or chose not to run it.

New York and Pennsylvania also investigated, had similar experiences with AIG stonewalling, and reached similar conclusions.

The New York report on three AIG companies said the deal with Coral Re was window dressing and didn’t transfer underwriting risk so AIG shouldn’t take credit for it. In plain English: the risk transfer was a sham. And New York described an accounting slight-of-hand which mirrors what indicted Enron officials did to change loans into earnings. In 1991, AIG insurance companies borrowed $190 million from an affiliate, AIG Funding Inc., but reported the loan as a sale to AIG Funding of their accounts receivable, ie. the money owed them by Coral. Presto, a loan became revenue. So, the New York examiners explained, the companies’ balance sheets did not have to show the loss.

Pennsylvania noted that AIG companies accounted for the most of Coral Re’s business, that some premiums to Coral Re were deposited into a bank owned by AIG, a substantial portion of the collateral used for the letters of credit was deposited at the same AIG bank and an AIG subsidiary, American International Management Company, Ltd. (Barbados) managed Coral Re. It found it noteworthy that Coral Re was incorporated on December 14, 1987, four days before the December 18, 1987 effective date of that replacement agreement with the AIG companies. It concluded, There was no transfer of insurance risk.

The Pennsylvania report said that books were kept in a way that prevented an audit trail for AIG company payments. The regulator told me, The people who worked there could never figure out what was going on, what the payments were for. It was like getting a bank statement without detail. They only have six main operating companies, the rest are all to confuse people. It was done intentionally, so nobody could understand what they’re doing.

Four states – Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, and California – met in 1996 to coordinate their reports on AIG. The SEC was also looking into the matter. The regulator said, The SEC came to me; they wanted to know if we were going to rule they were affiliated. Then there would be penalties, because if AIG was affiliated with Coral and they hadn’t disclosed it in 10k filings, that’s a ‘no-no’ with the SEC. It also would have been an issue for the IRS. If Coral Re was an AIG affiliate, it would have to pay taxes on its income. If it was independent, that money came tax-free.

But nobody had any guts; they wanted Delaware to say Coral Re is affiliated and use that to go after them, the regulator said. None of the agencies had the gumption to do it on their own.

And AIG wasn’t shy about using bully-boy tactics. He said, In 1996, AIG hired a private investigator to check into the background of the chief examiner in Delaware. The investigator actually told the department he was looking at the chief examiner at the request of AIG. It was intimidation. And Delaware officials allowed it to happen.

A Delaware examiner told the regulator. When you do something with this company, they make it so difficult for you, so people just let it go. And so, he said, Delaware reported what it found but didn’t rule that AIG and Coral Re were affiliated. That would have meant hearings, endless hassles. And real punishment for AIG.

AIG spokesman Andrew Silver told me that AIG was not involved in the offer and sale of Coral Re’s shares. That was done by Goldman Sachs, which approached potential investors with which it had relationships. AIG did not control or have an equity interest in Coral Re. The issue raised by the regulators was whether these transactions should be booked as a deposit account or an insurance acct. The regulators concluded that real risk was transferred and that these transactions should be accounted for as insurance. AIG insurance subsidiaries eventually commuted their Coral Re reinsurance.

Asked how AIG could say the regulators concluded that real risk was transferred when Pennsylvania stated clearly, There was no transfer of insurance risk, Silver had no comment.

David Schiff wrote in the trade paper Emerson, Reid’s that the sentiment that Greenberg is the proverbial 900-pound gorilla who sits wherever he wants to sit is etched in the negative space between each line of [Delaware’s] text. Although the implication was clear that Coral Re was actually an AIG affiliate and that AIG had accounted for its reinsurance transactions with Coral improperly, AIG was not fined, ordered to restate its financials, suspended, punished, or tarred, feathered, and run out of town on a rail. The Delaware Department merely gave AIG a dirty look and said don’t do this again.

The New York Insurance Department said the violations of New York law were not serious enough to warrant a fine. Besides, an official told me, it was hard to prove control of an offshore company. That, of course, is the reason for going offshore. The delays and stonewalling allowed AIG to use Coral Re for more than eight years. By the time it had to shut it down, it didn’t need it anymore.

AIG’s auditor Coopers & Lybrand (now PricewaterhouseCoopers) continued to give the company a clean verdict as it had every year since it started doing the books in 1988.

The trade publication Business Insurance editorialized on the timidity of regulators who gave AIG little more than a tap on the wrist in exchange for a promise not to do it again. It said, The message delivered here is that a company of AIG’s power and complexity can afford to be openly hostile to state oversight and, in the end, have things pretty much its own way. That is a disheartening message, indeed.

It sheds some light on the emails that AIG’s public relations agency Qorvis in October sent to financial commentators asking if they would – for up to $25,000 – – help AIG by criticizing Spitzer’s investigation and declaring that changing longstanding industry-wide practices is better left to regulators who understand the industry, rather than criminal investigators.

History of AIG

The American International Group at its origins was linked to the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) the forerunner of the CIA. It grew from the Asia Life/C. V. Starr companies founded by Cornelius Starr who started his insurance empire in Shanghai in 1919, the first westerner to market insurance in China.

Starr served with the OSS during World War II, and the Starr Corporation, located in the same building as the OSS in New York, provided intelligence on shipping, manufacturing and industrial bombing targets in Asia and Germany. The companies’ biggest shareholder was Starr International Company (SICO), a private holding company incorporated in offshore Panama and with principal executive offices in offshore Bermuda, to avoid U.S. regulation and taxes.

Starr had a wife with whom he was madly in love. He commissioned a painting of her by one of the best French painters, then discovered she was having an affair with the artist. Confronting her, he wrote out a check and proceeded to an amicable divorce. Starr forswore marriage, became a Buddhist and died childless in 1968. He left Greenberg a large block of Starr International stock.

The author is grateful to the Arkansas Committee for documents it provided on the AIG case. The committee was started in 1990 by University of Arkansas students, who, suspicious that the Arkansas Development Finance Authority was selling more bonds than it could use to finance state projects, demanded the agency’s documents under the Freedom of Information Act. It fought the case to the Arkansas Supreme Court before it got the papers describing the ADFA deal to buy shares of Coral Re. More details here.

Pingback: GRAY MONEY-How Slick Willy Clinton got his Name – ALPHA NEWS BY CF ZAP

Pingback: AIG's Past Could Return to Haunt : The Komisar Scoop