By Lucy Komisar

January 20, 2010

This article was written with support from WikiLeaks.

This article has prompted an investigation by Swiss authorities.

It’s widely believed that big corporations cheat on their taxes. But it’s hard to find the evidence to prove it. Here’s a case where a global company’s internal documents show how it’s done — in fascinating detail.

It’s widely believed that big corporations cheat on their taxes. But it’s hard to find the evidence to prove it. Here’s a case where a global company’s internal documents show how it’s done — in fascinating detail.

In September 2004, the tax director of the $20-billion Hong Kong-based Noble Group wrote a memo to company officials, expressing concern that if Swiss authorities discovered that a Noble subsidiary in Zurich was doing work which it pretended to contract to a fake company in Bermuda, the subsidiary might have to pay Swiss taxes.

What follows are the heretofore secret details about how that global company, Noble, used legitimate legal and accounting firms to create a fake structure to cheat on taxes. This was Switzerland, but it could be anyplace. Noble did what global companies do routinely. It’s called transfer pricing. It means pretending that work done in one country is really done in another. It’s an international scandal that costs developed and developing countries trillions of dollars in tax revenues.

The Noble Group is the world‘s second-largest commodities trading and logistics company, after Cargill. It specializes in energy, agriculture, mining and minerals. It is listed on the Singapore stock exchange (NOBG.SI). Is has a U.S. office in Stamford, CT.

Richard Elman, a British citizen who founded the Noble Group in 1986, owns 25 percent of Noble. He is worth $2.2 billion according to Forbes, making him number 437 of the world’s billionaires. The last company annual report listed Citibank Nominees, Singapore, as owner of 16% of the company. Last year, Noble sold 15% to the China Investment Corporation, the Chinese government’s sovereign wealth fund.

Noble’s Zurich subsidiary was Noble Investments SA (NISA), a hedge fund consultant. NISA specialized in the structuring and placement of alternative investment products, such as combinations of bonds and fund shares.

The fake company

Noble organized its tax evasion scheme by setting up a fake company in Bermuda to which to move some of its Zurich profits. The Bermuda company was called Noble Investments Ltd (NIL), also known as NIBU, for Noble Investments, Bermuda. The Zurich and Bermuda companies had the same shareholders. The story of their tax scam has not been told before.

In his internal memo, Noble Tax Director David Beringer said that in its disclosure to Swiss tax authorities, the Zurich company hadn’t reported that employees in Switzerland were doing NIL’s products structure and portfolio performance. There is concern that if the Swiss tax authorities learn that Swiss personnel are concluding NIL contracts, that NIL will be deemed to have a permanent establishment in Switzerland or that NIL will even be treated as a Swiss resident company,” he said. That could mean that “NIL would be exposed to a Swiss tax on a portion or all of its profits.”

The memo and other documents cited here were provided to this writer by Rudolf Elmer, a German who worked in Zurich for NISA as operations manager from June 2003 to October 2005. His responsibility included doing the accounts.

How the fake company worked

Bermuda has no corporate taxes; the Swiss levy is as much as 20%. So, Noble wanted to move taxable income to Bermuda. Elmer explained that NISA established the shell company Noble Investments Ltd, Bermuda (NIBU), to pretend that NIBU was handling its investment products — and deserved most of the profits — and that NISA was just an advisor. Swiss-based members of the NIBU board, who actually worked for NISA, Zurich, signed a consulting agreement with NISA to design products for NIBU. NISA would receive a fee for this work.

But NIBU existed only on paper. It had no physical presence and no staff in Bermuda. The phone directory didn‘t list it.

The Zurich company ran everything. Elmer said, “The actual work is performed in NISA, Switzerland, and all the decisions are taken in Switzerland. Management control of NIBU is in Switzerland. Its Zurich sales force performed the marketing, structuring, accounting, calculation and payment of commissions. It picked advisors for the portfolios and performed the marketing of the funds. Personnel in Switzerland signed NIBU`s contracts and intermediary agreements.

Elmer pointed out that in addition to tax evasion, “Noble had the advantage of putting liability for the products with the Bermuda company, which was the counterparty to the client.” That meant that anyone who sued would have to do so in Bermuda, making recovery difficult.

How it got started

Elmer said the idea for the scam originated with Noble, which in 2001 went to Attorney Thomas Graf, partner in the law firm Niederer Kraft & Frey, Zurich, to find out how to carry it out. Graf advised how to set up the tax reduction plan in a March 2001 memo to Noble: “It may be taken into consideration to establish an offshore subsidiary of Noble Investments SA and to carry out special business transactions with strong foreign relationship through this offshore subsidiary. However, such a structure must be negotiated in advance with the responsible Zurich tax inspector.”

Swiss income taxes are levied on three levels, on the federal level and on the state and community levels via the canton. Company profits are taxed flat by federal authorities at 8.5% based on profit after local taxes. On the canton level, tax ranges from 10% to 17%. The overall corporate income tax, including federal tax, in the canton of Zurich ranges from 18 to 20%.

The Zurich Tax Administration (ZTA) makes deals, called “tax rulings,” that allow companies and high-net-worth individuals to reduce their taxes. It does this out of competition with other cantons and nearby tax havens such as Liechtenstein and Luxembourg. The canton determination is the basis for federal taxation.

What they told tax authorities

NIBU was set up in June, a few months after Graf’s advice. In a letter that month to Zurich Tax Administration official Hansruedi Grundbacher, Graf wrote: “Noble Investments Ltd., Bermuda, will be the counterparty of all the consulting contracts with Investment Managers and all the contracts with the intermediaries.” Intermediaries –banks, self-employed relationship managers, accounting firms, trustees – buy investments for their clients.

He said, Noble Investments Ltd., Bermuda, will benefit from the know-how, the global net work and the Public Relations as well as Marketing of ![]() the Noble Group.”

the Noble Group.”

Graf said, “The products will not be directly distributed by the Noble Investments group [eg. neither by the Zurich nor Bermuda company]. The distribution will be made only via intermediaries such as banks, independent asset managers.”

It was a way to cover up the fact that NIBU didn‘t exist and couldn‘t do any work. It should have been obvious that NIBU‘s only task was putting its name to contracts.

Elmer said, “The counterparty of an agreement with intermediaries or clients is always NIBU, and the documents are signed by NISA (Zurich) officials and once in a while by Hong Kong or Jersey people, however, never by a person working for NIBU and based in Bermuda.”

For its “consultancy,” the Zurich company would be paid its operational costs plus 20% of the profits of Noble Investments Ltd, Bermuda. Elmer said the consultancy fee was calculated so that the profit was in line with what was agreed in the tax ruling. The rest of NIBU‘s profits would go to its shareholders, who happened to be the same as NISA‘s shareholders. They would get those profits tax-free.

Elmer added that Noble had another fake company, Noble Energy Ltd, in the Cayman Islands. He said, “It was used to lend Noble Investments Ltd, Bermuda, and Noble Investment SA, Zurich, loans to start up the business. Noble Energy Ltd, Caymans, was a finance company without employees, sitting in the Caymans and earning interest differentials.”

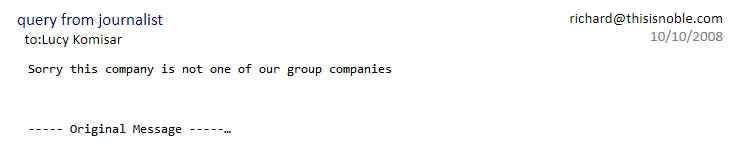

Elman wrote in reply to an email raising questions about NIBU, “Sorry this company is not one of our group companies.”

In fact, Elman signed a NIBU Bermuda registration document as company director in 2001. When he was sent the registration document, he did not respond. Noble’s 2003 annual report listed NIBU and NISA as subsidiaries. The 2007 report did not list either.

Zurich Tax Authorities reviewed NISA’s documents and assumed that what Graf said was true, that the Bermuda shell was an active investment firm. It approved the accumulation of profits offshore by NIBU Bermuda. According to the tax ruling, NISA was taxed on the higher of either cost +5% or cost +20% of the profit generated by NIBU.

Though the Zurich Tax Administration would not provide a copy of the tax agreement, its existence is confirmed by a May 27, 2002 letter from Graf to Thomas Gross, a board member of NISA and NIBU. It says: “In the Tax Ruling of June 22/June 28, 2002 and in the meeting with the Zurich tax commissioner it has been stressed that the financial and business risks are allocated to Noble Investments Ltd., Bermuda. Noble Investments SA shall render mere advisory services only. The remuneration scheme underlies this structure.”

Elmer said, “Things went very well and the company made several millions profit within two years.” A million Swiss francs was about $800,000.

The NISA tax self-assessment was due in September 2002, the month when all companies must file. Though Noble had gotten the nod from the Zurich Tax Administration, a tax decision based on its operations would be made by September 2003.

That could present a problem. Swiss law restricts the tax advantages of using an offshore jurisdiction where management control is in Switzerland. According to tax courts, the place of effective management and control of a company is the place where the ongoing business of a company is carried out and managed. In the practice of tax authorities, the following criteria in particular are applied to define the place of effective management and control for a legitimate offshore company:

How to decide if a corporation is really foreign

¢ The persons entrusted with the managing and decision-making functions are non-Swiss residents and are not working in Switzerland. The company has its own local staff, capable and skilled enough to manage and administer the company. The company has its own offices, telephone lines, fax, email, website, etc. Books, records and other business papers of the company are not kept in Switzerland. The bank accounts of the company are with non-Swiss banks.

¢ The person with signatory powers is a non-Swiss resident and is not working in Switzerland. The company‘s contracts and other documents are not signed in Switzerland.

¢ The board of directors is composed of non-Swiss residents. They have sufficient business skills and experience to carry out the managing functions and to take the necessary business decisions. They must not simply follow the orders of the Swiss parent company or the shareholders. The meetings of the board of directors are held locally. The general assembly of the shareholders is held locally.

¢ There are good business reasons for choosing the location of the company. The “foreign business case” of the company is supported by its P/L [profit and loss] and in particular by its cost structure.

But NIBU had:

¢ No physical presence in Bermuda. No offices, telephone lines, fax. No local staff, much less anyone capable and skilled enough to manage and administer the company. Books and records and other business papers kept with Noble Investments SA, Zurich.

¢ Management and decision-making persons who were Swiss and resident in Switzerland. A Board of Directors composed of Swiss residents. Directors who followed the orders of the Swiss operational personnel.

¢ No good business reasons for choosing the location of Bermuda.

In an interview, Graf insisted that the tax plan was never put into effect and that Swiss taxes were paid. He said, “The ruling was based on the condition the company [NIBU] had real activities.” And, “In the tax ruling there was a clear condition that one has to provide them with the financial statement of this NIBU; they had to file on an annual basis.” He explained, “The activities which the company [NISA] had the intention to allocate to this company have not been allocated to this company in practice.” He said, “At the end since there was not sufficient substance there, it was not allowed to allocate profits. At the end everything was taxed in Switzerland.”

Was NIBU a fake company? Graf was asked. “I don‘t say that isn‘t true,” he replied.

Backing up his assertion that the tax ruling was never put into effect, Graf argued that tax decisions usually take three or four years, so that the 2002 ruling would not have gone into effect by 2004. He said, “Usually in Switzerland, the process for a tax year starts many years later. It is usual that the tax year 2002 is assessed in 2005 or 2006.”

However, Alfred Walter, Deputy of the Zurich Tax Administration, suggested a shorter tax decision time line. He said a tax ruling “can go into effect for the next tax decision” if the business case on which the ruling is based is shown “in the books of the company (balance sheet/profit and loss account).”

Elmer said, Tax authorities from 2002 to 2004 assumed NIBU was a real company.” He said, The tax decision was implemented and it was accepted that NISA taxes were calculated only on the profit as shown in the excel sheets. As a result, he said, “The tax provision I made in the accounts from 2003 to 2005 and the tax paid during that period was based only on NISA‘s profits.”

He said, “I saw the tax payments to tax authorities. I know they didn‘t report full profit. They were reporting NISA profits as consulting fees. They said they got a consulting fee from NIBU. I did the calculation of the ˜consultant.‘ I was doing [the accounting for] NISA and NIBU. The operational costs of NISA in Zurich were deducted from the fee. So profit reported was consulting less operational cost.

Elmer said that Noble‘s Zurich auditor, Ernst & Young, was aware of the plan from the start. He said, “You need to provide a year-end audit report, which must agree with what you file with tax authorities. I wrote it and Ernst & Young signed it. It said NISA was getting consulting fees from NIBU. I knew it was a fake.”

Elmer said that Noble‘s Zurich auditor, Ernst & Young, was aware of the plan from the start. He said, “You need to provide a year-end audit report, which must agree with what you file with tax authorities. I wrote it and Ernst & Young signed it. It said NISA was getting consulting fees from NIBU. I knew it was a fake.”

Elmer said, “I did my inquiries because I was the CPA in the company, and everything would fall back on me if it were criminal. I talked to tax authorities informally and to colleagues. Then I was certain if a tax audit happened, the thing would cause a tremendous amount of additional tax for which I was not allowed to make a provision. E&Y Audit did also not care about it.

He added, “I had a big debate about this issue, but as CFO [Chief Financial Officer] I did not sign the NIBU accounts even though I had to prepare them.”

Elmer said that NISA presented those books and that the Zurich Tax Authority accepted them for its tax decisions. He noted, “We did not have to provide evidence. I had to instruct NISA ˜consultants‘ the way to argue so that the tax authorities would accept the fake construct.” He added, “I was not allowed to say that all the accounting was performed in Zurich at my desk.” Regarding Graf‘s claim that everything was taxed in Switzerland, Elmer said, “That’s not true, for instance, a hidden salary payment for Patrick Aregger [the CEO] paid in Hong Kong was not taxed in Switzerland.”

He said, “Graf knew preciously what was going on, because it was so obvious that all the product costs and income was posted through NIBU and the consulting, effective work, was provided by NISA.”

Swiss federal authorities get interested

Elmer says federal authorities indicated an interest the NISA/NIBU arrangement in 2004, but postponed their investigation until June 2005. Noble became concerned. Why an investigation? Elmer thought that authorities were suspicious because a company only three years old was paying managers bonuses of 4 to 6 million Swiss francs [$3.2 to $4.8 million].

David Beringer‘s September 2004 memo suggests he was worried because Noble had provided a “disclosure” to Swiss tax authorities and he feared the ZTA might find out that what Noble submitted was a fraud. Elmer said that Beringer talked with Graf about the matter in Zurich. Beringer told Graf in a memo: “In the disclosure to the Swiss tax authorities we have not advised that personnel working in Switzerland conclude NIL‘s contracts for fees for products structure and portfolio performance; and NIL‘s intermediary agreements.” NIL is NIBU.

There is concern that if the Swiss tax authorities learn that Swiss personnel are concluding NIL contracts that NIL will be deemed to have a permanent establishment in Switzerland or that NIL will even be treated as a Swiss resident company.” That could mean that “NIL would be exposed to a Swiss tax on a portion or all of its profits.”

How to invent a fake location for the fake company

So they had to invent evidence that NIBU existed. Beringer said that contracts should be executed out of Switzerland by non-Swiss personnel. He emailed colleagues in September and October 2004 about an attempt to create a more solid existence for NIBU. He reported a meeting with Stewart Walker, director of ASL Services in Jersey, a company that fakes real operations for shell companies.

He said, “Stewart is a director of ASL Management Services which assists companies with the sort of services we desire. [He] can provide us with dedicated phone and fax facilities which would help to beef up our non-Swiss substance claim.” They would be phone lines that dialed to Jersey but rang in Zurich where they could be answered. Beringer said that contracts should be executed in Jersey not Switzerland. “The less functions are carried out in Switzerland, the lower are the tax risks (as long as the compensation paid to NISA is still the same).” Beringer did not reply to emails seeking comment.

In October, Beringer, Graf and others exchanged emails about how to deal with the situation. One of the federal interests was VAT, Switzerland’s value added tax. If federal authorities did not accept that NIBU was a real company, the services NIBU sold would be subject to VAT.

Ernst & Young Tax Consulting VAT and Customs Advisory Group in reports in November 2003 and October 2004, made these written recommendations to Noble for adoption of proposals to prove that NIBU was an active investment company for the sake of VAT.

¢ Engage Jersey directors to serve on the Board of NIBU. Hold the meetings of the board of directors outside Switzerland. Hold the shareholders general assembly outside Switzerland. Appoint a Jersey secretary for NIBU.

¢ Use the office address in Jersey as the business address and install a dedicated telephone and a dedicated fax line there. Use Bermuda Telecom to redirect calls from Bermuda to Switzerland.

¢ Stop executing contracts in Switzerland; have contracts executed by non-Swiss personnel. Consider taking the administration function out of Switzerland. [This was not possible because the structurers of the products were Swiss residents.]

The measures would have created a better facade, but NISA would have continued to be the company carrying the business of creating and selling products, and NIBU would have remained a shell company with no justification other than accumulating tax-free profits offshore. Elmer said, “Ernst & Young, Zurich, offered to carry out the audit of Noble Investments, Bermuda, in Jersey even though it was aware that all the books and vouchers were kept in Zurich by Noble Investments SA, Zurich.” Elmer said Noble made only a few changes, for example using Jersey directors instead of Swiss directors.”

Dr. Alfred Raucheisen, director of corporate communications and marketing for Ernst & Young in Zurich, said in an e-mail that the company declined to comment.

What was the explanation for the urgent emails between Graf and Beringer? “I don‘t know,” Graf replied. And Hans Ulrich Meuter, head of division of service companies for the ZTA, who dealt with Noble, said, “I cannot give you information about this Noble company, because we have tax secrecy.”

Swiss investigate Noble

Elmer said that in 2005 there was federal tax investigation of NISA relating to federal withholding and Value Added Taxes. He said he was in a meeting with Graf and two federal tax authority employees. According to Elmer, “They said we looked at the set up and we believe that there is 1.2 million [$960,000] tax to be paid. They talked about withholding tax and VAT. They didn‘t give it in writing. Graf had to convince the federal tax authorities that the tax ruling and execution were according to the rules. And that NIBU was an effective company. I don‘t know if it was paid.”

He said, Fortunately I left the company early enough before the second tax investigation started. I was involved only in the first discussion, but I knew that is a real mess. If they look at the right place, tax evasion, even tax fraud could be claimed.”

The Noble Group annual report stopped listing NISA and NIBU in 2006, though NISA was still listed in the Zurich canton business register in May 2007. In December 2007, the company announced liquidation, and according to the Zurich register, the liquidation was still going at the last filing in October 2008. The company cannot be liquidated as long as any of the products it sold, such as bonds, have not matured.

Elmer said he did not know the reason for the liquidation. He said, “I know the performances of all the products were very poor and clients lost a lot of money. It is a similar thing with funds which do not perform – you‘d better liquidate them than spoil your reputation.” He noted, “There was also a tax investigation which started in October 2006 with respect to the tax ruling, but I do not know if this would have been the key factor for liquidation.

” * * * * * * * *

About Noble Group Ltd

Noble, based in Hong Kong, started as a commodities dealer and expanded globally to everything from the ethanol business in the U.S. to vessel chartering and fleet management in the U.K. Founder and CEO Elman, a British citizen, emigrated from the UK to Hong Kong in 1967. He spent a decade in New York for the commodity trading house, Philipp Brothers Inc., known as Phibro, which was a unit of Salomon Inc., the U.S. investment banking house. (A predecessor of Elman at Phibro was Marc Rich, indicted by the U.S. and then pardoned by Pres. Clinton for making illegal oil deals with Iran and for evading taxes.)

An American board member is Burton Levin, former U.S. ambassador to Burma and a visiting professor at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn. He did not respond to emails and phone calls requesting comment.

The firm has offices in Hong Kong, Lausanne, Stamford, CT, and Singapore, where it has been quoted on the Stock Exchange since 1997. Noble has companies in the U.S., the U.K., and Australia as well as firms registered in the offshore British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands and Panama. Noble Holdings Inc. is incorporated in Liberia.

Link to Board of directors and top staff.

Link to biographies of board and top staff.

Pingback: “Scoop” article prompts Swiss investigation | The Komisar Scoop